1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (36 page)

Read 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created Online

Authors: Charles C. Mann

Tags: #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Expeditions & Discoveries, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #History

Unlike mammalian urine, bird urine is a semisolid substance. Because of this difference, birds can build up reefs of urine in a way that mammals cannot (except, occasionally, for big colonies of bats in caves). Even among birds, though, Chincha-style guano deposits—heaps as big as a twelve-story building—are uncommon. To make them, the birds must be relatively large, form big flocks, and defecate where they live (gulls, for instance, release their droppings away from their breeding grounds). In addition, the area must be dry enough not to wash away the guano. The waters off the Peruvian coast receive less than an inch of rain a year. The Chinchas, the most important of Peru’s 147 guano islands, house hundreds of thousands of Peruvian cormorants, the most prolific guano producers. According to

The Biogeochemistry of Vertebrate Excretion,

a classic treatise by G. Evelyn Hutchinson, a cormorant’s annual output is about thirty-five pounds. Arithmetic suggests that the Chincha cormorants alone produce thousands of tons per year.

Centuries ago Andean Indians discovered that depleted soils could be replenished with guano. Llama trains carried baskets of Chincha guano along the coast and perhaps into the mountains. The Inka parceled out guano claims to individual villages, levying penalties for disturbing the birds during nesting or taking guano allocated to other villages. Blinded by the shine from Potosí silver, the Spaniards paid little attention to conquered peoples’ excremental practices. The first European to observe guano carefully was the German polymath Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt, who traveled through the Americas between 1799 and 1804. A pioneer in botany, geography, astronomy, geology, and anthropology, Humboldt had an insatiable curiosity about everything that crossed his path, including the fleet of native guano boats that he saw skittering along the Peruvian coast. “One can smell them a quarter of a mile away,” he wrote. “The sailors, accustomed to the ammonia smell, aren’t bothered by it; but we couldn’t stop sneezing as they approached.” Among the thousands of samples Humboldt took back to Europe was a bit of Peruvian guano, which he sent to two French chemists. Their analysis showed that Chincha guano was 11 to 17 percent nitrogen—enough to burn plant roots if not properly applied. The French scientists touted its potential as fertilizer.

Few took their advice. Supplying European farmers with guano would involve transporting large quantities of excrement across the Atlantic, a project that understandably failed to enthuse shipping companies. Within several decades, though, the picture changed. Agricultural reformers throughout Europe had begun to worry that the ever-more-intense agriculture necessary to feed growing populations was exhausting the soil. As harvests leveled off and even decreased, they looked for something to restore the land: fertilizer.

At the time, the best-known soil additive was bone meal, made by pulverizing bones from slaughterhouses. Bushels of bones went to grinding factories in Britain, France, and Germany. Demand ratcheted up, driven by fears of soil depletion. Bone dealers supplied the factories from increasingly untoward sources, including the recent battlefields of Waterloo and Austerlitz. “It is now ascertained beyond a doubt, by actual experiment upon an extensive scale, that a dead soldier is a most valuable article of commerce,” remarked the London

Observer

in 1822. The newspaper noted that there was no reason to believe that grave robbers were limiting themselves to battlefields. “For aught known to the contrary, the good farmers of Yorkshire are, in a great measure, indebted to the bones of their children for their daily bread.”

From this perspective, avian feces began to seem like a reasonable item of commerce. A few bags of guano appeared in European ports in the mid-1830s. Then Justus von Liebig weighed in. A pioneering organic chemist, Liebig was the first to explain plants’ dependence on nutrients, especially nitrogen. In his treatise

Organic Chemistry in Its Application to Agriculture and Physiology

(1840), Liebig criticized the use of bone fertilizer, which has little nitrogen. Guano was another story: “It is sufficient to add a small quantity of guano to a soil consisting only of sand and clay, in order to procure the richest crop of maize.” Liebig was enormously respected; he was an avatar of the Science that had brought new, productive crops like the potato and maize, and new ways of thinking about agriculture and industry.

Organic Chemistry

was quickly translated into multiple languages; at least four English editions appeared. Sophisticated farmers, many of them big landowners, read Liebig’s encomium to guano, flung down the book, and raced to buy it. Yields doubled, even tripled. Fertility in a bag! Prosperity that could be bought in a store!

Guano mania took hold. In 1841, Britain imported 1,880 tons of Peruvian guano, almost all of it from the Chincha Islands; in 1843, 4,056 tons; in 1845, 219,764 tons. In forty years, Peru exported about 14 million tons of guano, receiving for it approximately £150 million, roughly $13 billion in today’s dollars. It was the beginning of today’s input-intensive agriculture—the practice of transferring huge amounts of crop nutrients from one place to another, distant place according to plans dictated by scientific research.

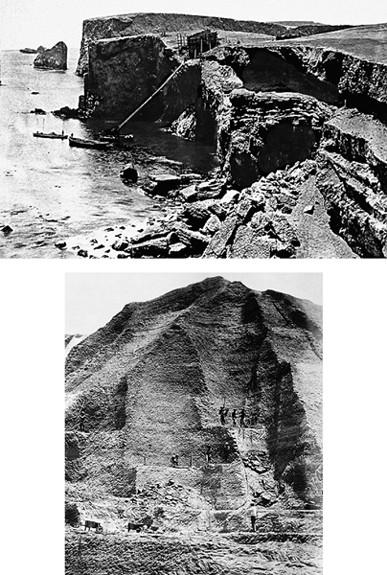

Hoping to take maximum advantage of the guano rush, Peru nationalized the Chinchas. Soon it discovered that nobody wanted to work on the islands. Except for birds, their only inhabitants were bats, scorpions, spiders, ticks, and biting flies. Not a single plant grew on their barren slopes. Worse, the islands had no water; every drop had to be shipped in. Because the land was blanketed in guano, miners worked, ate, and slept on shelves of ancient excrement. So little rain fell that the soluble materials in the guano never washed away—it remained studded with crystals of ammonia, which broke in corrosive clouds around miners’ shovels. Powdery and acrid, the guano went into miners’ carts, which were pushed up rails to a depot atop one of the seaside cliffs. From the cliff, men dumped tons of excrement through a long canvas tube directly into the bellies of vessels below. Slamming into the hold, guano dust exploded from the hatchways, shrouding the ship in a toxic fog. Workers wore masks made from hemp smeared with tar, one visitor noted,

but the guano mocks at such weak defenses.… [T]hey are unable to remain below longer than twenty minutes at one time. They are then relieved by another party, and return on deck perfectly naked, streaming with perspiration, and with their brown skins thickly coated with guano.

The government could have paid high wages to get workers to endure these terrible conditions, but that would have cut into profits. Instead it stocked the islands with a mix of convicts, army deserters, and African slaves. This arrangement proved unsatisfactory: the convicts and deserters killed each other, and the slaves were so valuable that their mainland owners did not wish to part with them. In 1849 Peru gave up trying to run the mines itself and awarded an exclusive concession to Domingo Elías, Peru’s biggest cotton grower and one of its principal slave owners. Politically savvy and manically ambitious, Elías had been prefect of Lima; during a time of civil unrest, he briefly declared himself ruler of the nation. In return for the monopoly, Elías was supposed to mine guano with his own slaves, but he, too, was reluctant to take them away from his cotton fields. He induced the government to subsidize merchants who imported immigrants. Prominent among these subsidized importers was Domingo Elías. By the time the law passed his agents were already in Fujian, waving labor contracts in the faces of illiterate villagers.

Thousands of Chinese slaves mined the guano of Peru’s Chincha Islands, shown here in 1865, for export to Europe as fertilizer. The islands, home for millennia to seabirds, were covered with a layer of guano as much as 150 feet deep. (

Photo credit 6.4

)

In standard indenture practice, the contracts promised the Chinese would pay for their passage by working, typically for eight years, in the newly discovered California gold fields. (The actual destination, the guano archipelago, was not mentioned.) The ruse was plausible: agents for U.S. firms were in Fujian at the same time, telling a similar lie as they sought indentured servants to build railroads. People who signed the bogus Peruvian contract were conducted to bleak human warehouses in Amoy (now called Xiamen, on an island across the river from Yuegang) and, later, Macao. People who refused to sign often were kidnapped and shipped to the same warehouses. In these dark confines slavers burned the letter

C

—for California, their ostensible destination—into the backs of their ears. No longer were the men described as workers. Their new name was

zhuzai,

little pigs. “None were let outside,” wrote the Shanghai historian Wu Ruozeng. “Those who resisted were whipped; any who tried to escape were killed.”

Peru was not the only destination in the mid-century Chinese diaspora. A quarter of a million or more

zhuzai,

almost all of them men, ended up—more or less willingly, more or less knowingly—in Brazil, the Caribbean, and the United States. But Peru represented the longest passage, the worst conditions, the most dreaded destination. Ultimately at least 100,000 Chinese were taken there. Conditions en route can be compared to those in the transatlantic slave trade. Perhaps one out of eight

zhuzai

died. As on the Atlantic slave ships, revolts were common. Eleven mutinies are known to have occurred on Peru-bound vessels; at least five bloodily succeeded.

Most of the Chinese ended up working in the sugar and cotton plantations on the coast. Some built the railroads that the Peruvian government was constructing with guano money. At any given time between one and two thousand were on the Chincha Islands. In classic divide-and-conquer fashion, Elías forestalled rebellion by setting his African slaves as overseers over his Chinese slaves and holding both to strict deadlines. Spasms of cruelty, slave upon slave, were the inevitable result. Guano miners swung their picks up to twenty hours a day, seven days a week, to fulfill their assigned daily quotas (as much as five tons of guano); two-thirds of their pay was deducted for room (reed huts) and board (a cup of maize and some bananas). Failure to meet the daily quota was rewarded with a five-foot rawhide whip. Minor infractions were punished by torture. Escape from the islands was impossible. Suicide was frequent. One overseer told a

New York Times

correspondent that

more than sixty had killed themselves during the year,…chiefly by throwing themselves from the cliffs. They are buried, as they live, like so many dogs. I saw one who had been drowned—it was not known whether accidentally or not—lying on the guano, when I first went ashore. All the morning, his dead body lay in the sun; in the afternoon, they had covered it a few inches, and there it lies, along with many similar heaps, within a few yards of where they were digging.

So many Chinese died that the overseers marked off an acre of guano as a cemetery.

Journalistic exposés of guano slavery created an international scandal that gave the Lima government an excuse to eject Elías and renegotiate the guano contract with someone else, thus procuring a second round of bribes. Fulminating against the evils of official corruption, Elías sought to regain his lucrative concession by twice staging a coup d’état. Both attempts failed. In 1857 he tried the legal route, running for president without success.

All the while guano flowed to Europe and North America. In addition to signing an exclusive mining concession with Elías, Peru had awarded a monopoly on shipping guano internationally to a company in Liverpool. With demand outstripping supply, Peru and its British consignees were able to charge high prices. Their customers reacted with fury to what they viewed as extortion. Decrying the “powerful monopoly” on guano, the British

Farmer’s Magazine

laid out its readers’ demands in 1854. “We do not get anything like the quantity we require; we want a great deal more; but at the same time, we want it at a lower price.” If Peru insisted on getting a lot of money for a valuable product, the only fair solution was invasion. Seize the guano islands!

From today’s perspective, the outrage—threats of legal action, whispers of war, editorials about the Guano Question—is hard to understand. But agriculture was then “the central economic activity of every nation,” as the environmental historian Shawn William Miller has pointed out. “A nation’s fertility, which was set by the soil’s natural bounds, inevitably shaped national economic success.” In just a few years, agriculture in Europe and the United States had become dependent on high-intensity fertilizer—a dependency that has not been shaken since. Britain, first to adopt guano and by far the largest user, was both the most dependent and the most resentful. Much as oil buyers today begrudge the member nations of OPEC, Peru’s British customers ranted about the guano cartel. They were apoplectic as Peru’s guano barons sauntered around Lima in the latest Parisian fashions, bejeweled trollops on their arms.