1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (37 page)

Read 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created Online

Authors: Charles C. Mann

Tags: #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Expeditions & Discoveries, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #History

Britons were almost entirely silent about Peru’s British agents in Liverpool, who used their share of the Peruvian monopoly profits to construct one of the biggest houses in England. Americans were not silent. They fumed as the British gave priority to their British customers, leaving Americans at the end of the guano line. Spurred by their fury, Congress passed the Guano Islands Act in 1856, authorizing its citizens to seize any guano islands they saw. The biggest loads came from Navassa, an island fifty miles south of Haiti, which the United States took in 1857. After the Civil War its workforce consisted largely of freed slaves. Conditions gradually deteriorated; the former slaves rebelled twice, killing some of their jailers, and the enterprise fell apart in a cloud of scandal. Under the aegis of the Guano Islands Act, merchants claimed title to ninety-four islands, cays, coral heads, and atolls between 1856 and 1903. The Department of State officially recognized sixty-six as U.S. possessions. Most proved to have little guano and were quickly abandoned. Nine remain under U.S. control today.

Guano set the template for modern agriculture. Ever since Liebig, farmers have treated the land as a medium into which they dump bags of chemical nutrients. The nutrients are shipped from far-off places or synthesized in distant factories. Farming is the act of transferring those external nutrients to crops in the field: high volumes of nitrogen go in, high volumes of maize and potatoes go out. Because the harvests in this system are enormous, the crops are no longer vehicles for local subsistence, but products destined for an international market. To maximize output, they are grown in ever-larger, single-crop fields—industrial monoculture, as it is called.

Today scholars often describe the “Green Revolution” after the Second World War—the combination of high-yield crops, agricultural chemicals, and intensive irrigation—as the moment when humankind triumphantly escaped, at least for a while, the limits set by small-scale farms and local resources. But as the Amherst College historian Edward D. Melillo has argued, the arrival of guano ships in Europe and the United States marked an earlier, equally profound Green Revolution, the first in a series of technological innovations that transformed life across the planet.

Before the potato and maize, before intensive fertilization, European living standards were roughly equivalent with those today in Cameroon and Bangladesh; they were below Bolivia or Zimbabwe. On average, European peasants ate less per day than hunting-and-gathering societies in Africa or the Amazon. Industrial monoculture with improved crops and high-intensity fertilizer allowed billions of people—Europe first, and then much of the rest of the world—to escape the Malthusian trap.

5

Incredibly, living standards doubled or tripled worldwide even as the planet’s population climbed from fewer than 1 billion in 1700 to about 7 billion today.

Along the way guano was almost entirely replaced by nitrates mined from vast deposits in the Chilean desert. The nitrates in turn were replaced by artificial fertilizers, made in factories by a process invented and commercialized in the early twentieth century by two Nobel-winning German chemists, Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch. No matter what their composition, though, fertilizers remain just as critical to agriculture, and through agriculture to contemporary life. In a fascinating 2001 study of the impact of factory-made nitrogen, Vaclav Smil, the University of Manitoba geographer, estimated that two out of every five people on earth would not be alive without it.

By any measure these were amazing accomplishments. Yet like all human endeavors the rise of intensive agriculture had its downside. The guano trade that launched modern agriculture was also the beginning, via the Columbian Exchange, of one of its worst pitfalls: the intercontinental transport of exotic pests. Proof will never be found, but it is widely believed that the guano ships carried a microscopic hitchhiker:

Phytophthora infestans. P. infestans

causes late blight, a plant disease that exploded through Europe’s potato fields in the 1840s, killing as many as two million people, half of them in Ireland, in what came to be known as the Great Hunger.

THOROUGHLY MODERN FAMINE

The name

Phytophthora infestans

means, more or less, “vexing plant destroyer,” a censure that is wholly deserved.

P. infestans

is an oomycete, one of seven hundred or so species sometimes known as water molds. From a biologist’s point of view, oomycetes can be thought of as cousins to algae. From a gardener’s point of view,

P. infestans

looks and acts like a fungus. It sends out tiny bags of six to twelve spores that are blown on the wind, usually for no more than twenty feet, occasionally for as much as half a mile or even further. When the bag lands on a susceptible plant, it hatches, so to speak, releasing what are technically known as zoospores: mobile, two-tailed cells that slowly swim through moisture on the leaf or stem, looking for the tiny respiratory holes called stomata. If the day is warm and wet enough, the zoospores germinate, sending long, threadlike filaments through the stomata into the leaf. Extensions from the filaments infiltrate leaf cells, hijacking the mechanisms inside; the plant ends up nourishing the invader, rather than itself. The first obvious symptoms—purple-black or -brown spots on the leaves—are visible in about five days. By that time it is often too late. Filaments lace through much of the plant. The oomycete is already generating new bags of spores.

Water is the blight’s friend—zoospores cannot germinate on dry leaves. Rain washes zoospores from the leaves onto the soil, letting them attack roots and tubers as much as six inches below the surface. Especially vulnerable are the tuber’s eyes.

P. infestans

strikes from the outside in, turning the potato’s outer flesh into dry, grainy, red-brown rot. Extensions of blight reach like dark claws toward the center of the tuber. Because the boundary between diseased and healthy tissue is indistinct, the entire potato must usually be thrown away. Care must be taken with disposal: a single infected tuber can generate a million spores.

P. infestans

preys on members of the nightshade family: potatoes, tomatoes, eggplants, sweet peppers, and weeds like hairy nightshade and bittersweet nightshade. When shocked European researchers first observed the carnage in potato fields, they naturally assumed the agent responsible came from Peru, the land of potatoes. Seventy years ago most changed their minds. Typically biologists view a species’s “center of diversity”—the place where it has the widest array of forms—as its ancestral home. Mexico has hundreds of varieties of maize seen nowhere else, suggesting that the species originated there. Africans are more genetically diverse than Caucasians or Asians; Africa is the cradle of humankind. And so on. In central Mexico,

P. infestans

seemed more varied than anywhere else. Notably, the species occurs in two types—one could think of them as male and female, except that oomycetes have no sexual characteristics—that can combine their DNA, creating an egg-like entity known as an oospore. In other words,

P. infestans

can reproduce both asexually and “sexually,” with the quotation marks as a reminder that these creatures are not male and female.

6

But only in Mexico did the oomycete reproduce sexually, because the rest of the world lacked one of the two forms. Scientists argued that this and other types of diversity indicated that

P. infestans

originated in Mexico—even though there is no evidence of

S. tuberosum

there until the eighteenth century. Alexander von Humboldt, visiting Mexico in 1803 with his samples of guano, made the first certain observation of a potato in Mexico. Humboldt assumed that Spaniards had imported the tuber from the Andes. The potato blight had existed for millennia, in this view, before it encountered a potato. A final detail: because blight was spotted in the United States before Europe, some researchers suggested that it spread there first, then hopped a boat across the Atlantic.

In a series of experiments culminating in 2007, a team led by University of North Carolina plant geneticist Jean Ristaino overturned these ideas. Ristaino’s team used the tools of DNA analysis to examine blight from 186 infected potatoes in herbariums, the botanical storehouses in museums. The youngest sample was from 1967; three were collected in Europe in 1845–47, the time of the Great Hunger. Ristaino’s scheme was complex in detail, but simple in principle. Because

P. infestans

usually reproduces asexually, the progenitor oomycete and its offspring usually have identical genetical endowments, except for the infrequent occasions when a mutation scrambles DNA. Organisms with similar DNA patterns belong, as geneticists say, to the same “haplogroup.” If two individuals belong to the same haplogroup, it is molecular evidence that they share a recent ancestor. Similarly, different haplogroups are a sign of the lack of a recent common ancestor. Ristaino’s team found that potato blight from the Andes had a greater number of haplogroups than Mexican blight—it was fundamentally more diverse. Moreover, DNA from the old blight in herbariums—samples preserved for as long as a century and a half—was nearly identical to DNA from Andean blight. “The U.S. and Irish populations were not genetically differentiated from the Peruvian populations,” the scientists wrote. Blight from the Andes “initiated epidemics first in the U.S. and then Ireland that led to the famine.”

Most likely the blight traveled from Peru to Europe aboard a guano ship to Belgium, probably to Antwerp, the area’s most important port. Farmers in the adjacent province of West Flanders were having trouble with their potatoes. In what would now be described as a demonstration of the power of evolution, European plant pathogens—viruses and fungi—were adapting to the new crop. In July 1843 the provincial council of West Flanders voted to import new varieties of potato from North and South America, hoping some would prove to be less susceptible to the diseases. No record exists of their origins or the means by which they were shipped. It would be odd, though, if the South American potatoes had not come from the Andes.

Almost certainly the potatoes made the journey on a guano ship. Between 1532 and 1840 few ships passed directly from Peru to Europe, because Spain, protective of its silver in Potosí, tightly controlled traffic. As Potosí ran out of ore, the silver ships sailed less frequently. In the 1820s Bolivia and Peru gained their independence and Spanish shipping there closed down altogether. European ships were then free to sail to Lima, but few did: the new nations had little to offer and were politically chaotic to boot. In its first two decades, Peru had more than one change of government per year; it also fought five foreign wars. A direct shipping line between Peru and Britain did not open until 1840. It carried guano. As guano frenzy set in, ships by the score sailed from Europe to the Chincha Islands. One traveler there in 1853 saw 120 vessels clustered about the guano docks. Another, later voyager saw 160. Chances are high that one of these ships unknowingly carried blighted potatoes to Belgium—and infected a continent.

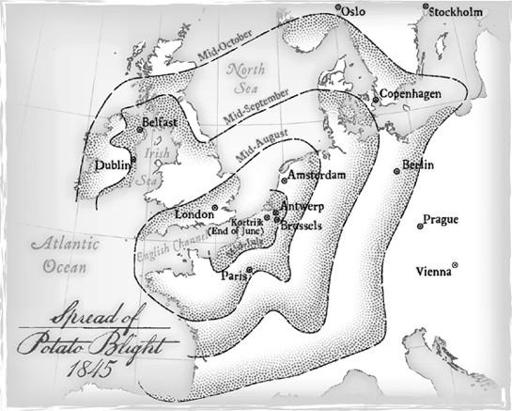

Field trials of West Flanders’s new potatoes began in 1844. That summer a nearby French botanist observed a few potato plants with strange, bruise-dark spots. The following winter was extremely cold, which should have killed any blight spores or eggs in the soil. But the experimenters may have stored a few contaminated potatoes and unknowingly planted them the next spring. In July 1845 the West Flanders town of Kortrijk, six miles from the French border, became the launchpad for Europe’s first widespread epidemic of potato blight. Carried by windblown spores, the oomycete hopscotched to farms around Paris by August. Weeks later, it was in the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, and England. Governments panicked and ordered more potatoes from abroad.

Blight was first reported in Ireland on September 13, 1845. By mid-October the British prime minister was privately describing the epidemic as a national disaster. Within another month between a quarter and a third of the crop had been lost. Cormac Ó Gráda, an economist and blight historian at University College, Dublin, has estimated that Irish farmers planted about 2.1 million acres of potatoes that year. In two months

P. infestans

wiped out the equivalent of between half and three-quarters of a million acres in every corner of the nation. The next year was worse, as was the year after that.

Recall that almost four out of ten Irish ate no solid food except potatoes, and that the rest were heavily dependent on them. Recall, too, that Ireland was one of the poorest nations in Europe. At a stroke, the blight removed the food supply from half the country—and there was no money to buy grain from outside. The consequences were horrific; Ireland was transformed into a post-apocalyptic landscape. Destitute men lined the roads in their rags, sleeping in crude shelters dug into roadside ditches. People ate dogs, rats, and tree bark. Reports of cannibalism were frequent and perhaps accurate. Entire families died in their homes and were eaten by feral pets. Disease picked at the survivors: dysentery, smallpox, typhus, measles, a host of ailments listed in death records as “fever.” Mobs of beggars—“homeless, half-naked, famishing creatures,” one observer called them—besieged the homes of the wealthy, calling for alms. So many died that in many western towns the bodies were interred in mass graves.