1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (4 page)

Read 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created Online

Authors: Charles C. Mann

Tags: #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Expeditions & Discoveries, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #History

A grand monument to the admiral! To del Monte y Tejada, the merits of the idea seemed obvious; Colón was a messenger from God, his voyages to the Americas the result of a “divine decree.” Nonetheless, building the monument took almost a century and a half. The delay was partly economic; most nations in the hemisphere were too poor to throw money at a monstrous statue on a faraway island. But it also reflected the growing unease about the admiral himself. Knowing what we know today about the fate of the Indians on Hispaniola, critics asked, should there be any monument to his voyages at all? Given his actions, what kind of person was buried in the golden box at its center?

The answer is hard to arrive at, even though his life is among the best documented of his time—the newest edition of his collected writings runs to 536 pages of small print.

During his lifetime, nobody knew him as Columbus. The admiral was baptized as Cristoforo Colombo by his family in Genoa, Italy, but changed his name to Cristovao Colombo when he moved to Portugal, where he was an agent for Genoese merchant families. He called himself Cristóbal Colón after 1485, when he moved to Spain, having failed to persuade the Portuguese king to sponsor an expedition across the Atlantic. Later, like a petulant artist, he insisted that his signature be an incomprehensible glyph:

(No one is sure what he meant, but the third line could invoke Christ, Mary, and Joseph—

Xristus Maria Yosephus

—and the letters up top may stand for

Servus Sum Altissimi Salvatoris

, “Servant I am of the Highest Savior.” Χρο FERENS is probably

Xristo-Ferens

, “Christ-Bearer.”)

“A well-built man of greater than average stature,” according to a description attributed to his illegitimate son Hernán, the admiral had prematurely white hair, “light-colored eyes,” an aquiline nose, and fair cheeks that readily flushed. He was a mercurial man, moody and inconstant one hour to the next. Although subject to fits of rage, Hernán remembered, Colón was also “so opposed to swearing and blasphemy that I give my word I never heard him say any oath other than ‘by San Fernando.’ ” (St. Ferdinand). His life was dominated by overweening personal ambition and, arguably more important, profound religious faith. Colón’s father, a weaver, seems to have scrambled from debt to debt, which his son apparently viewed with shame; he actively concealed his origins and spent his entire adult life striving to found a dynasty that would be ennobled by the monarchy. His faith, always ardent, deepened during the long years in which he was vainly begging rulers in Portugal and Spain to back his voyage west. During part of that time he lived in a politically powerful Franciscan monastery in southern Spain, a place enraptured by the visions of the twelfth-century mystic Joachim di Fiore, who believed that humankind would enter an age of spiritual bliss after Christendom wrested Jerusalem from the Islamic forces who had conquered it centuries before. The profits from his voyage, Colón came to believe, would both advance his own fortunes and fulfill di Fiore’s vision of a new crusade. Trade with China would pour so much money into Spain, he predicted, “that in three years the Monarchs will be able to set about preparing for the conquest of the Holy Land.”

Integral to this grand scheme were Colón’s views on the size and shape of the earth. As a child, I—like countless students before me—was taught that Columbus was ahead of his time, proclaiming the planet to be large and round in an era when everyone else believed it to be small and flat. My fourth-grade teacher showed us an etching of Columbus brandishing a globe before a platoon of hooting medieval authorities. A shaft of sunlight illuminated the globe and the admiral’s flowing hair; his critics, by contrast, squatted like felons in the shadows. My teacher, alas, had it exactly backward. Scholars had known for more than fifteen hundred years that the world was large and round. Colón disputed both facts.

The admiral’s disagreement with the second fact was minor. The earth, he argued, was not perfectly round but “in the shape of a pear, which would all be very round, except for where the stem is, where it is higher, or as if someone had a very round ball, and in one part of it a woman’s nipple would be put there.” At the very tip of the nipple, so to speak, was “the Earthly Paradise, where nobody can go, except by divine will.” (During a later voyage he thought he had found the nipple, in what is now Venezuela.)

The king and queen of Spain cared not a whit about the admiral’s views of the world’s shape or heaven’s location. But they were keenly interested in his ideas about its size. Colón believed the planet’s circumference to be at least five thousand miles smaller than it actually is. If this idea were true, the gap between western Europe and eastern China—the width, we know today, of both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and the lands between them—would be much smaller than it actually is.

The notion enticed the monarchs. Like other European elites, they were fascinated by accounts of the richness and sophistication of China. They lusted after Asian textiles, porcelain, spices, and precious stones. But Islamic merchants and governments stood in the way. If Europeans wanted the luxuries of Asia, they had to negotiate with powers that Christendom had been at war with for centuries. Worse, the mercantile city-states of Venice and Genoa had already cut a deal with Islamic forces, and now monopolized the trade. The notion of working with Islamic entities was especially unwelcome to Spain and Portugal, which had been conquered by the armies of Muhammad in the eighth century and had spent hundreds of years in an ultimately successful battle to repel them. But even if they did make arrangements with Islam, Venice and Genoa stood ready to use force to maintain their privileged position. To cut out the unwanted middlemen, Portugal had been trying to send ships all the way around Africa—a long, risky, expensive journey. The admiral told the rulers of Spain that there was a faster, safer, cheaper route: going west, across the Atlantic.

In effect, Colón was challenging the Greek polymath Eratosthenes, who in the third century

B.C.

had ascertained the earth’s circumference by a method, the science historian Robert Crease wrote in 2003, “so simple and instructive that it is reenacted annually, almost 2,500 years later, by schoolchildren all around the globe.” Eratosthenes concluded that the world is about twenty-five thousand miles around. The east-west width of Eurasia is approximately ten thousand miles. Arithmetic would require that the gap between China and Spain be about fifteen thousand miles. European shipbuilders and potential explorers both knew that no fifteenth-century vessel could survive a voyage of fifteen thousand miles, let alone make the return trip.

Colón believed that he had, as it were, disproved Eratosthenes. A skilled intuitive seaman, the admiral had plied the eastern Atlantic from Africa to Iceland. During these travels he used a sailor’s quadrant in an attempt to measure the length of a degree of longitude. Somehow he convinced himself that his results vindicated the claim, attributed to a ninth-century caliph in Baghdad, that a degree was 560 miles. (It is actually closer to sixty-nine miles.) Colón multiplied this value by 360, the number of degrees in a circle, to calculate the circumference of the earth: 20,400 miles. Coupling this figure with an incorrectly large estimate of the east-west length of Eurasia, Colón argued that the journey across the Atlantic could be as little as three thousand miles, six hundred miles of which could be cut off by setting sail from the newly conquered Canary Islands. This distance could easily be traversed by Spanish vessels.

Crossing their fingers that Colón was right, the monarchs submitted his proposal to a committee of experts in astronomy, navigation, and natural philosophy. The committee of experts rolled its collective eyes. From its perspective, Colón’s claim that he—a poorly educated man fumbling with a quadrant on a wave-tossed ship—had refuted Eratosthenes was like someone claiming to have demonstrated in a backwoods shack that gravity didn’t pull iron as much as scientists thought, and that one could therefore hoist an anvil with a loop of thread. In the end, though, the king and queen ignored the experts—they told Colón to try the thread.

After landing in the Americas in 1492, the admiral naturally claimed that his ideas had been vindicated.

3

The delighted monarchs awarded him honors and wealth. He died in 1506, a rich man surrounded by a loving family; nevertheless, he died a bitter man. As evidence had emerged of his failings, personal and geographical, the Spanish court had revoked most of his privileges and shunted him aside. In the anger and humiliation of his later years, he slid into religious messianism. He came to believe that he was God’s “messenger,” destined to show the world “the new heaven and earth of which Our Lord spoke through Saint John in the Apocalypse.” In one of his last reports to the king, the admiral suggested that he, Colón, would be the ideal person to convert the emperor of China to Christianity.

Much the same mix of grandiosity and disappointment characterized the Columbus monument. Del Monte y Tejada’s proposal for a memorial to the admiral was finally approved in 1923, at a meeting of the Western Hemisphere’s governments. Progress was slow—the design competition wasn’t held for another eight years, and the monument itself wasn’t built for another six decades. During most of that time the Dominican Republic was ruled by the tyrant Rafael Trujillo. A classic case of narcissistic personality disorder, Trujillo erected scores of statues to himself and hung a giant neon sign that read “God and Trujillo” over the harbor of Santo Domingo, which he had renamed Trujillo City. As his reign grew more barbarous, international enthusiasm for the lighthouse waned—supporting the project was seen as endorsing the dictator. Many nations boycotted the inauguration, on October 12, 1992. Pope John Paul II reneged on his promise to celebrate a Mass at the opening, though he did appear nearby a day before. Meanwhile, protesters set police barricades on fire, denouncing the admiral as “the exterminator of a race.” Residents of the walled-off slums around the monument told reporters that they thought Colón deserved no commemoration at all.

A thesis of this book is that their belief, no matter how understandable, is mistaken. The Columbian Exchange had such far-reaching effects that some biologists now say that Colón’s voyages marked the beginning of a new biological era: the Homogenocene. The term refers to homogenizing: mixing unlike substances to create a uniform blend. With the Columbian Exchange, places that were once ecologically distinct have become more alike. In this sense the world has become one, exactly as the old admiral hoped. The lighthouse in Santo Domingo should be regarded less as a celebration of the man who began it than a recognition of the world he almost accidentally created, the world of the Homogenocene we live in today.

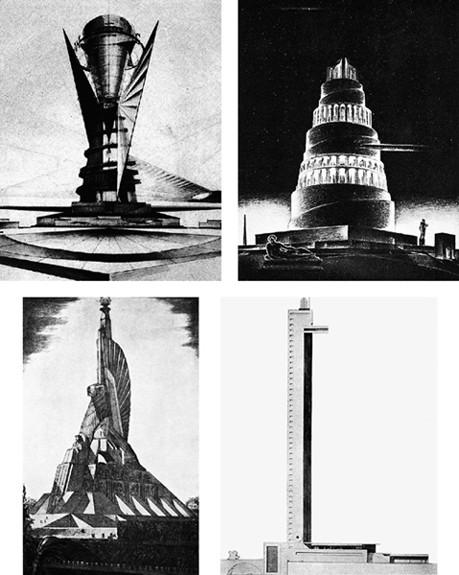

Every American nation promised to contribute to the Columbus memorial when it was approved in 1923, but the checks were slow in coming—the U.S. Congress, for example, didn’t appropriate its share for another six years. In May of 1930 Dominican army head Rafael Trujillo became president in a fraud-ridden election. Three weeks later a hurricane wiped out Santo Domingo, killing thousands. Deciding that the memorial would symbolize the city’s revitalization, Trujillo staged a design competition in 1931. On the jury were eminent architects, including Eliel Saarinen and Frank Lloyd Wright. More than 450 entries came in, including these by (clockwise from top left) Konstantin Melnikov, Robaldo Morozzo della Rocca and Gigi Vietti, Erik Bryggman, and Iosif Langbard. (

Photo credit 1.2

)

SHIPLOADS OF SILVER

At a busy corner in a park just south of the old city walls in Manila is a grimy marble plinth, perhaps fifteen feet tall, topped by lifesize bronze statues, blackened by pollution, of two men in sixteenth-century attire. The two men stand shoulder to shoulder, faces into the setting sun. One wears a monk’s habit and brandishes a cross as if it were a sword; the other, in a military breastplate, carries an actual sword. Compared to the Columbus Lighthouse, the monument is small and rarely visited by tourists. I found no mention of it in recent guidebooks and maps—a historical embarrassment, because it is the closest thing the world has to an official recognition of globalization’s origins.