A Government of Wolves: The Emerging American Police State (33 page)

Read A Government of Wolves: The Emerging American Police State Online

Authors: John W. Whitehead

Over the course of World War II, the German pharmaceutical corporation, Bayer A.G of Leverkusen, made extensive use of death-camp inmates for their experiments on human beings. Bayer laboratories synthesized a new anti-typhus medicine and wanted it tested. The medicine came in two forms: tablet and powder. Bayer wanted to know which one had the fewest side effects. Bayer researchers were given permission to conduct their experiments on death camp inmates.

624

Auschwitz Concentration Camp

(Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Medical experiments conducted by the Third Reich and its corporate enablers fell into two general categories: 1) use prisoners to conduct tests that would have been normal attempts at advancing medical knowledge had the subjects participated willingly and 2) discover means to ensure German rule over Europe forever. The mass sterilization of Jews, Gypsies, and other undesirables by the Nazi regime fell into the latter category, and the death camps were the place to carry it out. In this nightmare vision, as Rubenstein realized, "the victims would have had as little control over their own destiny as cattle in a stockyard. In a society of total domination, helots could be killed, bred, or sterilized at will."

625

This practice of using prisoners was not unique to Nazi Germany or other totalitarian regimes. No government holds a monopoly on the mentality that sees powerless human beings as unwilling or unsuspecting subjects of experiments on behalf of the "greater good." During the Cold War, the practice of using prisoners for medical experiments was very common in the United States as well.

626

In the notorious Tuskegee syphilis experiment, the U.S. government sought to study the natural progression of untreated syphilis by deceiving black prisoners into thinking they were receiving free health care. Those who received the placebo endured the full effects of the disease and/or death in the name of scientific progress.

627

This experiment only differed from those carried out by the Nazis in that the American prisoners were completely blind to what was being done to them whereas the Nazi victims had some idea of what was happening.

This psychopathic "modern" mentality, which places a higher priority on "solving an administratively defined problem" rather than focusing on its social consequences on human beings, characterized both the American and German experiments. Yet even though the numerous accounts of corporate complicity with the Third Reich are shocking and appalling, Rubenstein adamantly refutes the notion that the "corporate executives [were] possessed of some distinct quality of villainy"

628

Mass murder simply became part of business and a successful corporate venture.

Unless we ignore the socio-economic factors that facilitated the justification of massive killings, as Rubenstein recognizes, we cannot assume that it cannot happen elsewhere or in future times.

629

The lesson is clear: it is a stern warning for citizens and policy-makers today as the police state continues to spread its tendrils into everyday life with the assistance of better and more efficient technology in an attempt to profit from prison labor.

"Laws are rules made by people who govern by means of organized violence, for non-compliance with which the non-complier is subjected to blows, to loss of liberty, or even to being murdered."

630

–Author LEO TOLSTOY

W

hy did Nazi soldiers commit unspeakable atrocities at Hitler's request? Why do so many of us stand by silently when we witness bullying?

It appears that we, as humans, implicitly comply with authority. Furthermore, when in positions of authority, we innately act aggressively.

Thankfully, most of us will not have to confront a warlord or find ourselves in the position to seriously harm others. However, some groups in modern society, namely police and corrections officers, too often abuse their authority. Understanding why we create and allow hostility will enable us to create more effective safeguards against unnecessary violence.

The Experiments

In 1961 professor Stanley Milgram conducted an experiment at Yale University in which subjects were asked to administer an increasingly intense shock punishment to a friend or acquaintance

631

in another room whenever he or she answered a question wrong.

632

The test subjects believed they were causing another human being great harm, even though in reality they were not. Despite the fact that many subjects were visibly uncomfortable (nervously laughing, etc.) with giving painful shocks to another human being, twenty-six out of forty participants continued shocking people up to the highest (450-volt) level, labeled "XXX" on the machine. No subject stopped before giving a 300-volt shock, labeled "Intense Shock" despite the fact that the confederate in the next room expressed severe agony and health concerns. All of the subjects were voluntary participants. When a participant expressed an unwillingness to administer the next shock, experimenters prodded them to do so by asking "Please continue," or stating: "The experiment requires that you continue."

633

A decade later, researchers conducting the Stanford Prison Experiment

634

randomly assigned participants to be either guards or prisoners in an intricate role play. With only the instruction to "maintain order" in the simulated prison, the "guards" began harassing and intimidating prisoners. "Prisoners" did attempt to rebel, but always returned to compliance quickly after an outburst, despite the fact that they were volunteers. Due to the extreme aggression of guards, the experiment was terminated after only five days (the original design would have held students for two weeks).

In the decades following these shocking studies, psychologists have asked, why do people (those in power or those subordinate to power) act aggressively? Organizations like the military or police force have been widely studied to answer this question. Today, theories of learned obedience are generally accepted.

For example, a SWAT member who believes a raid is unconstitutional will likely not defy orders from his superior because compliance was engendered in him during the training process. Norm Stamper, a former police chief, believes that the current "rank-and-file" organization of police departments results in "bureaucratic regulations [being emphasized] over conduct on the streets."

635

In war zones, soldiers are trained as subordinates and fulfill their superior's commands. Milgram's participants felt they were under the employ of the researchers and took the orders issued to them. Stamper argues that utilizing similar rigid power hierarchies in police departments leads to blind obedience. Researcher Eungkyoon Lee backs up Stamper's musings with empirical research. Lee found that trait compliance is highest in contexts that feature a well-defined authority figure and when the subject in question has a clearly inferior role.

636

Pleasure in Violence?

Unfortunately, merely reorganizing systems of authority will not end excessive compliance. Individuals can, without orders from a superior, still act violently, as the Stanford Prison Experiment showed. Observational evidence, like the infamous smiles on the faces of American soldiers stationed at Abu Ghraib, has long suggested that it is human nature to take pleasure in violence. Following the 1992 Rodney King incident, police brutality became a hot-button topic, especially as it relates to whether individuals who are predisposed to enjoy violence seek out positions as police officers. According to a study done by Brian Lawton, such self-selection into law enforcement does occur.

637

Making matters worse, "non-lethal" weapons such as tasers, pepper spray, and so on enable police to aggress with the push of a button, making the potential for overblown confrontations over minor incidents that much more likely. Case in point: the fact that seven-months-pregnant Malaika Brooks was tased three times

638

for refusing to sign a speeding ticket, while Keith Cockrell was shot with a taser for jaywalking.

639

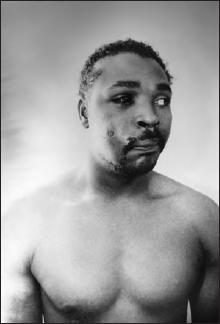

Rodney King (AP Photo)

After the advent of automatic weapons, psychologists began examining whether or not modern weapons had their own independent effect on violent behavior. Researchers discovered that dehumanizing weapons like guns or tasers, which do not require the aggressor to make physical contact with his victim, are aggression-eliciting stimuli. One study found that simply showing an image of a gun to students caused them to clench their fists faster (a sign of aggressive effect) when presented with an aversive situation.

640

If a simple handgun can noticeably increase violent behavior, one can only imagine what impact the $500 million dollars' worth of weapons and armored vehicles (provided by the Pentagon to local police in states and municipalities across the country) have on already tense and potentially explosive situations.

641

The Bystander Effect

While explanations have been proffered for the inclination towards violence on the part of law enforcement officials, what isn't immediately evident is why the American citizenry doesn't take a stand against such tactics. What, psychologically, is holding us back from staving off the emerging police state? Social psychologists believe the answer is centered on our group dynamics.

In 1964 dozens of onlookers witnessed the brutal murder of Kitty Genovese in Queens, New York, but no one called the police or took any other action to stop the crime.

642

This widely-reported case became the archetypal example of the "bystander effect" defined as people doing nothing in response to some injustice because they believe another witness will take responsibility for the situation.

From the film Obedience

(© 1968 by Stanley Milgram; copyright renewed 1993 by Alexandra Milgram; distributed by Alexandra Milgram)

An offshoot of the bystander effect–a desire to conform to the group–could also be responsible for the lack of outcry against the growing police state. We all want to fit in: if our peers aren't doing something, we probably won't either. A recreation of Milgram's shock experiments that involved allowing participants to watch one another administering shocks found that people were systematically more likely to "conform" to the group behavior (be it administering shocks or refusing From the film

Obedience

to shock).

643

As a species, (© 1968 by Stanley Milgram; copyright renewed 1993 by ™ learn bv modeling the Alexandra Milgram; distributed by Alexandra Milgram) behavior of our peers and parents. Thus, it is not surprising that we put so much weight on the group norm. Indeed, doing what the group does can be an incredible tool when learning social standards, a new physical skill or how to cope with difficult emotions.