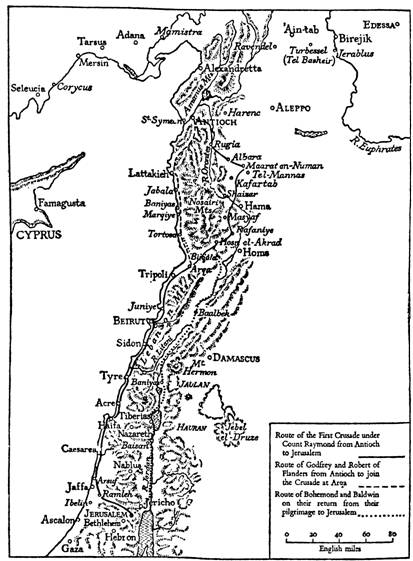

A History of the Crusades-Vol 1 (32 page)

Attack on Maarat

an-Numan

In the debates that followed Kerbogha’s defeat,

the princes had vowed to start for Jerusalem in November. On 1 November they

began to assemble at Antioch to discuss their plans. Raymond came from Albara,

where he had left most of his troops. Godfrey rode in from Turbessel, bringing

with him the heads of all the Turkish prisoners that he had made in a series of

small raids in the district. The Count of Flanders and the Duke of Normandy

were already at Antioch; and Bohemond, who had been ill in Cilicia, arrived two

days later. On the 5th the princes and their advisers met together in the

Cathedral of St Peter. It appeared at once that there was no agreement between

them. Bohemond’s friends opened by claiming Antioch for him. The Emperor was

not coming; and Bohemond was an able man and the Crusader of whom the enemy was

most afraid. Raymond retorted by sharply reminding the assembly of the oath to

the Emperor that all except himself had sworn. Godfrey and Robert of Flanders

were known to favour Bohemond’s claim, but dared not speak up for it for fear

of the accusation of perjury. The argument continued for several days.

Meanwhile the soldiers and pilgrims waiting outside for a declaration grew

impatient. Their one desire was to carry out their vows and to reach Jerusalem.

They longed to leave Antioch where they had delayed so long and suffered so

much. Spurred on by Peter Bartholomew and his visions, they presented an

ultimatum to their chiefs. With an equal contempt for both Bohemond’s and

Raymond’s ambitions, let those, they said, that wished to enjoy the revenues of

Antioch do so, and let those that were eager for gifts from the Emperor await

his coming; for themselves they would march on to Jerusalem; and if their

leaders continued to haggle over the possession of Antioch they would raze its

walls before they left. Faced with this and fearing that Raymond and Bohemond

would soon resort to arms, the more moderate leaders suggested a more intimate

discussion which only the chief princes would attend. There, after further

angry scenes, a temporary arrangement was made. Raymond would agree to the

decisions that the council might ultimately make about Antioch, so long as

Bohemond swore to accompany the Crusade on to Jerusalem; while Bohemond took an

oath before the bishops not to delay nor harm the Crusade to suit his personal

ambitions. The question of Antioch was not settled; but Bohemond was confirmed

in his possession of the citadel and three-quarters of the town, while Raymond

remained in control of the fortified bridge and the palace of Yaghi-Siyan,

which he placed under William Ermingar, The date for the departure for

Jerusalem was still unfixed; but, to occupy the troops meanwhile, it was

decided to attack the fortress of Maarat an-Numan, whose reduction was

advisable to protect the army’s left flank when it should advance southward

towards Palestine.

On 23 November Raymond and the Count of

Flanders set out for Rugia and Albara and on the 27th they reached the walls of

Maarat an-Numan. Their attempted assault on the town next morning was a

failure; and when Bohemond and his troops arrived that afternoon and a second

assault also failed, it was decided to conduct a regular siege. But, though the

town was completely invested, for a fortnight no progress was made. The

countryside had to be scoured for wood to make siege machines. Food was short;

and detachments of the army would desert their posts in order to search for

corn and for vegetables. At last on 11 December, after Peter Bartholomew had

announced that success was imminent, a huge wooden castle on wheels, built by

Raymond’s men and commanded by William of Montpelier, was pushed against one of

the city towers. An attempt to scale the tower from it was repulsed; but

protection given by the castle enabled the wall on one side of the tower to be

mined. In the evening the wall collapsed and a number of humble soldiers forced

their way into the town and began to pillage. Meanwhile Bohemond, jealous of

Raymond’s success and eager to repeat his coup at Antioch, announced by a

herald that if the town surrendered to him he would protect the lives of all

the defenders that took refuge in a hall near to the main gate. During the

night the fighting died down. Many of the citizens, seeing that the defences

were pierced, fortified their houses and cisterns but offered to pay a tax if

they were spared. Others fled to the hall that Bohemond had indicated. But when

the battle reopened next morning no one was spared. The Crusaders poured into

the town, massacring everyone that they met and forcing an entrance into the

houses, which they looted and burnt. As for the refugees who relied on Bohemond’s

protection, the men were slaughtered and the women and children sold as slaves.

During the siege Bohemond’s and Raymond’s troops

had co-operated with difficulty. Now, when Bohemond by his treachery had

secured the greater part of the loot though it was Raymond’s army that had

taken the town, the enmity between the southern French and the Normans flared

up again. Raymond claimed the town and wished to place it under the Bishop of

Albara. But Bohemond would not evacuate his troops unless Raymond abandoned his

area of Antioch and, as a counter-attack, he began openly to question the

authenticity of visions reported by Peter Bartholomew.

Meanwhile disaffection increased in the whole

army. Raymond’s troops in particular demanded the resumption of the march on

Jerusalem. About Christmas Day representatives of the soldiers indicated to

Raymond that if he would organize its departure the army would recognize him as

leader of the whole Crusade. Raymond felt that he could not refuse, and a few

days later he left Maarat an-Numan for Rugia, announcing that the expedition

was about to leave for Palestine. Bohemond thereupon returned to Antioch; and

Maarat an-Numan was put into the hands of the Bishop of Albara.

Raymond’s Army

Sets out for Jerusalem

But even after his announcement Raymond

delayed. He could not bring himself to leave for the south with Antioch in

Bohemond’s hands. Bohemond, seeing, perhaps, that the more Raymond hesitated

the more mutinous grew his troops, and knowing that the Emperor would not come

down across Asia Minor during the winter months, suggested a postponement of

the expedition till Easter. To bring matters to a head, Raymond summoned all

the princes to meet him at Rugia. There he attempted to buy them to accept his

leadership. The sums that he offered presumably corresponded to the strength

that each now possessed. To Godfrey he proposed to give ten thousand sous and the

same to Robert of Normandy, to Robert of Flanders six thousand, five thousand

to Tancred and lesser sums to the lesser chiefs. Bohemond was offered nothing.

He had hoped that he would thus be established as unquestioned head of the

Crusade and could thus keep Bohemond in check. But his overtures were received

very coldly.

While the princes conferred at Rugia, the army

at Maarat an-Numan took direct action. It was suffering from starvation. All

the supplies of the neighbourhood were exhausted; and cannibalism seemed the

only solution. Even the Turks were impressed by its tenacity in such

conditions, though, as the chronicler Raymond of Aguilers sadly remarks: ‘We

knew of this too late to profit by it.’ The Bishop of Orange, who had some

influence over the Provencals, died from these hardships. At last, despite the

protests of the Bishop of Albara, the men determined to force Raymond to move

by destroying the walls of Maarat an-Numan. At the news, Raymond hurried back

to the town but realized that there could be no more postponement.

On 13 January 1099, Raymond and his troops

marched out of Maarat an-Numan to continue the Crusade. The Count walked

barefoot, as befitted the leader of a pilgrimage. To show that there would be

no turning back the town was left in flames. With Raymond were all his vassals.

The Bishop of Albara and Raymond Pilet, lord of Tel-Mannas, deserted their

towns to travel with him. The garrison that he had kept at Antioch under

William Ermingar could not hold out against Bohemond and hastened after him. Of

his colleagues among the princes, Robert of Normandy at once set out to join

him, accompanied by Tancred, whom Bohemond doubtless wished to watch over

Norman-Italian interests in the Crusade. Godfrey of Lorraine and Robert of

Flanders hesitated for nearly a month before public opinion forced them to

follow. But Baldwin and Bohemond remained in the lands that they had captured.

Thus the quarrel between the two great princes

seemed to have found a solution. Raymond was now unchallenged leader of the

Crusade; but Bohemond was in possession of Antioch.

BOOK V

THE PROMISED LAND

CHAPTER I

THE ROAD TO

JERUSALEM

‘

Therefore

now go, lead the people unto the place of which I have spoken unto thee.’

EXODUS

XXXII, 34

Syria at the time

of the First Crusade

The Syrian Emirs

When Stephen of Blois, writing to his wife from

Nicaea, had expressed the fear that the Crusade might be held up at Antioch, he

never dreamed how long the delay would last. Fifteen months had passed since

the army had reached the city walls. During this period there had been

important changes in the Moslem world. The Fatimids of Egypt, like the

Byzantines, had, before the Crusade began, recovered from the first shock of

the Turkish onslaught, and, like the Byzantines, they hoped to use the Crusade

to consolidate their recovery. The real ruler of Egypt was Shah-an-Shah

al-Afdal, who had succeeded his father, the Armenian renegade Badr al-Jamali,

as vizier to the boy Caliph, al-Mustali. Al-Afdal’s embassy to the Crusader

camp at Antioch had not produced any results. Frankish ambassadors had returned

with his envoys to Cairo; but it soon was clear that they were not authorized

to negotiate an alliance and that the Crusaders, far from being willing to aid

the Egyptians to recover Palestine, had every intention of themselves marching

on Jerusalem. Al-Afdal therefore determined to profit by the war in northern

Syria. As soon as he heard of Kerbogha’s defeat at Antioch and realized that

the Turks throughout Asia were in no position to resist a new attack, he

invaded Palestine. The province was still in the hands of the sons of Ortoq,

Soqman and Ilghazi, who admitted the suzerainty of Duqaq of Damascus. As

al-Afdal advanced they retired behind the walls of Jerusalem. They knew that

Duqaq could not at once come to their aid; but they hoped that the great

fortifications of Jerusalem and the fighting ability of their Turcoman troops

would enable them to hold out till rescue came. Al-Afdal’s army was equipped

with the latest siege machines, including forty mangonels; but the Ortoqids

resisted for forty days, till at last the walls were so battered that they were

forced to capitulate. They were allowed to retire with their men to Damascus,

whence they went on to join their cousins in the district round Diarbekir. The

Egyptians then occupied the whole of Palestine and by the autumn had fixed

their frontier at the pass of the Dog River, on the coast just north of Beirut.

In the meantime they repaired the defences of Jerusalem.

In northern Syria the local Arab dynasties were

equally delighted by the collapse of Turkish power and were ready to make terms

with the Franks. Even the Emir of Hama, Ridwan’s father-in-law, and the Emir of

Homs, who had fought well for Kerbogha, abandoned any idea of opposing them.

More important to the Crusaders was the attitude of the two leading Arab

families, the Munqidhites of Shaizar and the Banu ‘Ammar of Tripoli. The former

controlled the country immediately ahead of the Crusaders, from the Orontes to

the coast, and the latter the coast line from the middle Lebanon to the Fatimid

frontier. Their friendship, or at least their neutrality, was essential if the

Crusade was to advance.

From Maarat an-Numan Raymond marched on to

Kafartab, some twelve miles to the south. There he waited till 16 January,

collecting provisions to revictual his troops; and there Tancred and Robert of

Normandy joined him. Thither, too, came ambassadors from the Emir of Shaizar,

offering to provide guides and cheap provisions for the Crusaders if they would

pass peaceably through his land. Raymond accepted the offer; and on the 17th

the Emir’s guides conducted the army across the Orontes, between Shaizar and

Hama, and led it up the valley of the Sarout. All the flocks and herds of the

district had been driven for safety into a valley adjoining the Sarout; into

which, by error, one of the guides introduced the Franks. The herdsmen and the

local villagers were not strong enough to prevent the Franks from

systematically taking over the beasts. The commander of the castle that

dominated the valley thought it best to buy immunity for himself. So rich was

the booty that several of the knights went off to sell their surplus in Shaizar

and in Hama, in return for pack-horses, of which they bought a thousand. The Arab

authorities freely allowed them to enter their towns and make their purchases.