A Thousand Laurie Lees (4 page)

Read A Thousand Laurie Lees Online

Authors: Adam Horovitz

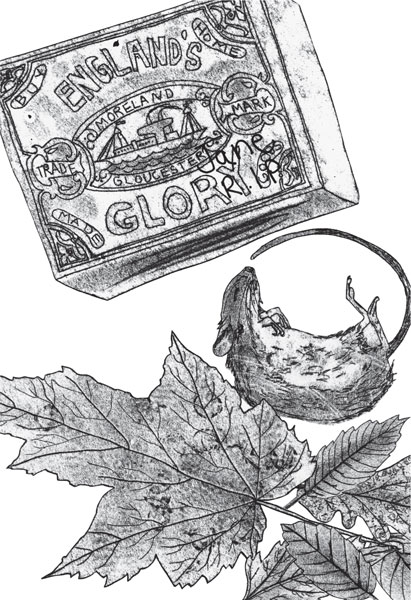

I learned to adore people other than my mother at Bisley Bluecoats, too; a pretty young girl called Jane Millin caught my fancy aged seven and I was so enamoured of her that I named my pet mouse Jane in her honour. That fancy was brought to a crushing end when, at my eighth birthday party, Skanda Huggins told everyone who would listen exactly why I had a mouse called Jane, a wicked glint in his eye. I remember walking around the house distraught, the chill of betrayal cold as an owl’s shadow hovering over me as the party spirit shivered and was stilled inside me.

That autumn, my father left the mouse house outside overnight, and Jane died in a sudden frost, as dead to me as I was to Jane Millin.

![]()

Getting to school was another adventure; with both parents working from home or away there was no regular bell to leave the house. It was up to me to move once I was out of the house and I was a dreamy child quite prepared to get lost in the hedgerows, watching the rabbits flit across the road in an angry, bobbing flash of white.

No matter that I was supposed to meet Katy at her house and walk up the hill with her to meet Doug, local postman and school-day cabbie, revving his homely chariot at the top of the steep hill at quarter to nine dead on – I still remembered the first day of school, the wrench of leaving the valley’s apron strings and my mother behind to slip through the kissing gate into the beehive swarm of school; I trod ever so slowly up the hill.

Too easily distracted by springtime primroses or the venous scrabble of winter trees against the sky, I was always beaten to the taxi by Katy and only dragged out of my reveries by the hollow echo of a hooting car and Doug’s amused and irritated cry of ‘come on lightning’.

Katy, a small blonde avalanche rumbling with discontent in the back seat, would scowl at me, poke me in the ribs and roundly insult me for being a slowcoach all the way to school; a daily routine of dominance that we had invariably forgotten by first break. Unlike Rowena, the other passenger whom the car picked up first from Througham; she took it into her heart and head to maintain an antipathetic attitude towards my endless dreamy lateness that lingered far beyond playtime, unbroken but for the one time my school photos didn’t come out and I was dragged from my maudlin state by her arm around my shoulder, hugging gently and shocking away the onset of tears.

![]()

When the snows came, so did adventure. The long crawl out of the valley to school – or work for my mother – often assisted by Norman Williams’ tractor from Stancombe Farm, left us with choices. Being a village school, Bisley Bluecoats was open to all except the furthest flung, those who could not or would not escape their rural confines. Unless the snows cut the power off entirely, caved in the school’s ceiling or simply came in a vengeful whirlwind and carried all the teachers away, we were expected to be there to learn, or understand at least that huddling together to keep warm was a fairly sure method of survival.

Sometimes the drifts swarmed higher than my head in a bid to shut us in – the lightning fork junction at the top of the hill where Doug the cab-driving postman would pick up Katy and, eventually, myself for school once drifted to six feet and didn’t melt for weeks. We badgered our parents daily to be taken there to slide and climb and revel in the mountainous nature of the snow and it meant so much that to this day I’d still believe that Katy and I ventured up there every time entirely on our own, had she not in her possession parent-taken photos to prove otherwise.

My mother, on these snowy days, would pull out all the stops, bank up the fire and enter into a domestic frenzy in a bid to keep warm. The old house was tricky to heat – at least until the two-and-a-half-foot deep walls had soaked in enough warmth to begin radiating it back into the room. Once that had happened it felt like summer in the front room and springtime in the kitchen. The upstairs could feel like winter if we weren’t careful with the night storage, but a tightly clutched hot-water bottle and a dash for bed was all the sport I needed to keep warm at night – sleep was only a rugby tackle away.

The house was soundtracked by ‘Baby Love’ or Peruvian flute music to keep us moving, whatever the weather. I can still smell the landscape around Slad when I hear certain records, wherever I am: Charlie Mingus’s

The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady

evokes the stark and autumnal birdland we found walking in the woods, a dark mulch hiding bright wintry flashes of mushroom and sheep skull, the subtly shifting shadow towers of tree and a horn-scatter of pigeons; The Supremes’ burst of morning sunshine – a spring day, bright as primroses; the haunting stream-song of

La Flute Indienne

cutting through a sticky summer; the all-encompassing

Abbey Road

, any time of year, anywhere, like the sun cutting through cloud, me with a nickel toffee hammer clutched in my hand, beating time to ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’ in the front room by the fire, or staring out of the bathroom window wondering which fast-flitting bird or deft squirrel darting along the low-slung yew might suddenly turn my way and put Sunday on the phone to Monday and Tuesday on the phone to me.

The house was all movement in winter days: the gentle shift of curtains when the draught excluder was out of place at the door and the fire was sucking in the cold, like an old man with a pipe, to stoke itself; the chatter from upstairs of my father’s typewriter, his papers banked up around him like a frozen tidal wave of words, a staccato rhythm simmering under the music, following and dictating in the fire’s percussion; me dancing in the wake of my mother as she shuffled through the routines of cooking, her mind on me, on other things, part of it quite somewhere else.

If it was too cold or bleak to go out walking, she would bend to the boredom and isolation of the winter by learning new things to make – the progress of the cheese soufflé she taught herself is deeply imprinted on me, starting out as a gooey but edible volcanic mess (edible, at least, if you are a devoted son who knows too well the effects of belt-tightening, even if you do not understand the causes) and eventually becoming an impossibly light, balloon-like explosion of taste that one had to be ready for when the oven door opened. We were invariably ready, my father and I, like a couple of greedy chicks opening their mouths wider than their bodies and clamouring for more, more, more.

These were only the inward, tiny winter adventures – my father would be away in London reading poetry, and sometimes my mother would have to cast off her domestic feathers and rise out of the snow to travel to Bristol to perform for the BBC. Suddenly the quiet domesticity of the valley would vanish and all would change, would become flowers. One memorable day, having scrambled through the snow to our car, parked far away at the top of the hills where the snow lay lighter, my mother paused at Stancombe’s grass triangle junction, now a muddy white, and stared down the snow-bound fields marked out in kanji like a series of haiku.

‘I’m going to be late,’ she said, eyeing the slippery and barely troubled road. ‘Or you are.’ She looked at me, a half-smile on her mouth, guessing my answer before her question.

‘Do you want to come to Bristol with me, or would you rather go to school?’

Out of the snow, out of school, off into the city. I remember watching her, silently, through the studio glass, bristling with the sense of a landscape in her voice as she recorded poetry for radio, the seed of a realisation that it mattered to listen, to take in the cadences of one’s surroundings as much as the voices of the people, growing in my ear.

3

I

lived, then, in a small, enclosed galaxy, caught partly out of time between two villages, with few facilities but the ones we built for ourselves or the ones some long-evaporated glacier had gouged and melted into the valley millennia ago.

Electricity was a fairly new phenomenon in the valley – the mullioned cottage in which we lived, capped with a caul of yew, had only been wired up and connected to the water mains twenty or so years before we moved in. We were often travelling out, to Bisley, to Stroud and beyond, out of the enclosed sphere of the valley and into other worlds. We travelled less often to Slad, however; Slad was

us

and

other

at the same time, a smoke signal puff of civilization at the end of the valley. We could see it clearly from our garden, it was a mere two-mile stroll from our door, but the village always seemed far away.

It was due to the lack of a road in that direction, and the lack of a shop in Slad, the latter a change wrought in the wake of electricity and cars taking trade to larger villages and towns. Walking was for pleasure and escape; without the rattling, coughing second-hand car my mother had learned to drive whilst pregnant with me, we would have felt almost entirely divorced from the wider world.

We would strike out in Slad’s direction often enough to visit Diana Lodge, the painter friend of my mother’s, who was the first point on the erratic diamond of people who we knew in this valley before we came ourselves. Her house, Trillgate, was halfway to Slad and we would walk a quarter of a mile or more through mud and cowslips, avoiding horses and the occasional bull the farmer had forgotten to fence away from the footpath (which had once been the main road between Slad and Bisley) before we hit the tarmac, but we rarely walked on into the village itself.

Diana kept a caravan up in the Black Mountains, at Capel-y-ffin, just around the corner from the old monastery where Eric Gill had lived and worked, and where Gill’s granddaughter and her family, the Davieses, still lived. My mother had met Diana there, visiting the old monastery with her mentor (and later my godfather) Father Brocard Sewell, a friend of Gill’s in his youth. She became one of my mother’s dearest friends.

A game and eccentric woman – she seemed to me to be built out of milk and mountains and to be as old and wise as the hills, though she was the same age as my grandmother – Diana had lived an extraordinarily full life. She married the poet Oliver W.F. Lodge in 1932, having initially answered his advertisement for a nude model, and had previously posed for Eric Gill and danced with the high-kicking Tiller Girls.

Diana and Oliver travelled, to Canada and the United States, gathering up a whorl of friends such as Lynn Chadwick and his first wife, the Canadian poet Ann Secord, who also found their way back to the area of Gloucestershire where Oliver had settled with his first wife, before her death, on the estate near Painswick of Detmar Blow, the Ruskin acolyte.

After Oliver’s death, and after teetering on the verge of becoming a nun when her relationship with Leopold Kohr broke up, Diana embedded herself in Trillgate and into the landscape of Slad, becoming so much part of it that it seemed to me that she had never been anywhere else, despite painting the Black Mountains as well as the Slad Valley in an astonishing array of watercolours that captured the exactitudes of the landscape in a faintly surreal technicolour palate, and which she exhibited and sold in aid of charity until the end of her life.

Like her watercolours, Trillgate existed in a little bubble of faded Cotswold grandeur; a set of semi-modern kitchen units tacked on to the heart of an old, old house that ran you in circles if you walked through it and felt brave enough to walk through Diana’s spartan bedroom and back down the worn stone semi-spiral of stairs that wound around the chimney stack. Kitchen and bedroom were very likely all there had been of the house once, and they were all that mattered of the house – as a child I ran through the chilly bedrooms and freezing drawing room, only stopping to hide in a tipped-up basket of an armchair next to the unlit fireplace, ready to leap out on unwary passers-by, or simply staring at the hugger-mugger collection of Diana’s paintings, which filled the vast dining table and the nooks and crannies around it, but I did not linger in these rooms.