A Young Man's Passage (21 page)

Read A Young Man's Passage Online

Authors: Julian Clary

What I didn’t know (and how could I?) was that things were about to change. Moves were afoot, a TV channel was in the making, a programme being conceived that would change my life for the better, bringing me the excitement and adoration that eluded me. Fate was about to stir things up for the better. Had I known, I’d have grinned and borne it. Farewell south-east London housing estate, farewell gigs above pubs, and farewell anonymous gay cruising. For a while, anyway.

SEVEN

‘The worst thing about having success is trying to find someone who is happy for you.’

BETTE MIDLER

OVER THE NEXT

few years my life seemed to improve in a series of leaps and bounds. Whether this was due to some beneficial astrological alignment I cannot say, but I was grateful for each happy change. There was a positive progression at work, each step seemingly connected to the one before, as if I was a character in a film, the plot of which was racing towards my fulfilment. The first area of my life that destiny took charge of was my location.

As we know, I was residing in a one-room council flat in deepest south-east London. I had kept the local kids at bay on the Brooke Estate with the occasional free helium-filled balloon, but local youths were not so easily won over. They had eyed me suspiciously from day one, and when they saw me emerging from the van one afternoon in my Tarzan costume, their dark mutterings denoted trouble ahead. They did the only thing possible and tried to kick my door down. When this failed they poured sugar into my petrol tank.

The next morning a letter arrived from the Seymour Housing Co-op in Marylebone informing me that they now had some vacancies and would I like to come for an interview? I had registered with them several years earlier and forgotten all about it. The co-op was fabulously located in Seymour Place, W1, and consisted of about fifty flats clustered round a charming communal garden, secure and safe behind a big, dark-red iron gate. When I went along and explained my plight they were most sympathetic, and within weeks I had moved in. I loved it so much there I thought I would never move out again. Flat 21 was another studio flat, but bright and sunny. A pillar in the middle of the room separated the bed from the living area, and it boasted the luxury of separate bathroom and kitchenette. The fortnightly co-op meetings were fun, my neighbours were cheery and I was a five-minute stroll away from Hyde Park. I gave up the balloon deliveries and the Honda van.

It was a few weeks after this that I went into hospital and had the anal warts forcibly removed. My personal comfort, inside and out, was complete. I thanked the Lord.

Ye Gods now seemed to be turning their attention towards my career. I joined an improvised comedy workshop run by Kit Hollerbach at The Comedy Store, which improved my confidence when messing about with punters during my act. I had plenty of work and was able to declare myself officially self-employed. In 1985 I did 144 gigs, and in 1986 the number had risen to 195. I became very business-like on the telephone, arranging my bookings and negotiating my fee. I was now one of the stalwarts of the comedy circuit, but apart from the listings magazines I received little media attention. I wasn’t yet labelled ‘limp-wristed camp comic’ by the tabloids. But people were starting to take interest. I became fashionable, in a cultish, underground sort of way.

The Times

wrote: ‘His timing is impeccable, his tongue razor-sharp, as he satirises anything from Joan Collins to surrogate motherhood. Fanny the Wonder Dog, his tiny honey-coloured mongrel, sits deadpan at his side throughout.’

Time Out

did a spread on me with nice big colour pictures. ‘In such celebrated but frankly dingy venues as The Comedy Store, possibly London’s most famous underground car park, Clary seeks to create a world of glitter and glamour . . . but his main aim is to insult the audience,’ wrote Malcolm Hay. I liked the way he finished his article: ‘If you want to catch the act, my best advice is don’t sport a Marks and Sparks jumper or a centre parting. One other thing – watch out for the smile on the face of the tiger.’ I sent it to my parents with a note: ‘Here’s a little light reading which might make a welcome change from the

Telegraph

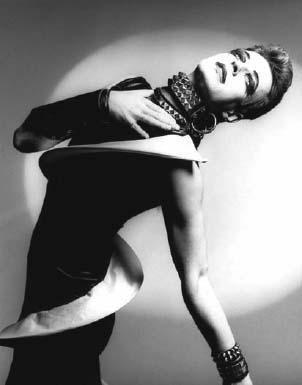

. . .’ I was anxious to impress them. They had never seen my act. They knew I wore make-up and a lot of black rubber and I wondered if they thought it was far more sinister than it really was.

Family was very important to me. I phoned my mother every few days and went home every few weeks with my dirty washing, accompanying mother to church on a Sunday morning. My sisters were both married and nephews and nieces featured. At Christmas and Easter we all gathered together and cards were played, the same catchphrases passed down from one generation to the next. One Christmas Auntie Tess played cards for 16 hours with only the briefest of lavatory breaks.

These were happy, carefree days. Fanny and I trotted off to work with our trusty white suitcase, on a Saturday maybe squeezing three gigs into the evening: The Comedy Store in Leicester Square at 8 p.m. and midnight, and in between a dash across Soho in full slap to the Chuckle Club, run by the aromatic Eugene Cheese.

We travelled about a lot too, to university gigs or provincial comedy clubs. Sound systems that crackled, dressing rooms that stank, punters who didn’t listen and doormen who refused to let dogs on the premises were all everyday obstacles. But we went anywhere that wanted to book us, and stayed in grim B&Bs where necessary:

16 December 1986

Fanny and I have to laugh sometimes. We find ourselves at the Chatsworth Guesthouse in Bristol, a small terraced house. ‘No Vacancies’ sign proudly displayed in the window. The concierge is old with a cough.

The decor in our twin room is a symphony in pink. Three walls ice cream pink, the wall opposite me salmon. There is a grey-and-white speckled carpet with root-like squiggles of black, red and blue. On top of this between the beds is a brown mat, elaborately patterned with darker brown rings and sunset red small, medium and large squares, each of which is afflicted with the root problem first noted in the grey carpet. Curtains are red faded to orange with large hand sized daisy chains from top to bottom, filled out with smaller white freesias. (And nets of course). Matching duvet covers in maroon and purple floral effect with differing pillow slips: pink and white nylon. The under sheet is nylon with suspiciously rubbery under cover. There are two chairs, a wardrobe, a small chest and a small black and white television.

The fire instructions suggest: ‘Attack the fire if possible with the appliance provided.’ The remaining feature of the room is the sink with cold (true) and hot (untrue) running water.

I also had an interesting sideline going as a member of a pop group called Thinkman. The record producer Rupert Hine, together with the lyricist Jeannette Obstoj, had created a nifty album about media hype called

The Formula

. To market the album they plucked three likely-looking young actors from the pages of the actor’s directory

Spotlight

and passed us off as musicians. Together with Rupert we were Thinkman.

The three of us sat bemused in Jeannette’s Connaught Street living room and listened as she rolled an unfeasibly large joint and explained that the con we were about to pull on the music industry was all in keeping with the concept of the album. We were each given new names and assigned a musical instrument. I was Leo Hurll, keyboard player. Andy was bass guitarist and Greg was to play drums. We were given fake biographies to learn and driven to a warehouse in Battersea where we were given lessons in miming our instruments. ‘This is mad!’ we three would whisper to each other when Rupert and Jeannette weren’t listening, but as they were paying us £150 a day to enter into the fantasy, we just went with the flow. We wondered what on earth we were getting ourselves into, but a stylist dressed us in expensive designer clothes and we dutifully turned up to film a big-budget video. There was a huge industrial set: cameras, photographer, make-up artists, record company executives, catering trucks – it all seemed to be happening for real. The champagne and joints helped things along. On set and off we were referred to by our new names. We learnt the lyrics and bashed away at our (unplugged) instruments as we mimed:

It’s an interview

But it’s a second take

There’s a questioner

But your mind’s at stake

.

Let’s break down the formula

Let’s switch off the set

. . . and be glad we finally met

.

Then at the end of the day we were thanked and returned to our own, mundane lives, pop stars no more.

A few months later Jeannette called to say we were in the German and Canadian charts and were required to fly to Europe to do press and television appearances to promote ‘our’ album. I cleared a few days of cabaret shows out of the way, assumed my Leo Hurll persona and off we flew on a whistle-stop tour of Germany and Belgium. We sat on sofas to be interviewed on serious music programmes, reeled off the fibs from the fake biogs and took to the stage, ‘playing’ and pouting to excited girls who called out our names and threw soft toys at us. We were then bundled into a people carrier with blacked-out windows and whisked to the airport to fly off to the next city and repeat the proceedings all over again. If we had dinner in our posh hotel at the end of the day it was with a number of top management from the record company who had all swallowed our collective lie, and so the charade had to be kept up relentlessly. There was one tricky moment when a Belgian suit pointed to the piano in the corner of the restaurant and asked me to play something. I was so immersed in being Leo I almost agreed. ‘Shall I?’ I said. Rupert glared at me, Greg sniggered. After an awkward pause I decided on a pop-star-like response and said, ‘Nah. Fuck off,’ and everyone laughed nervously. ‘Girlfriend trouble . . .’ Rupert explained to the suit.

We had three or four trips abroad like this. I loved having a secret other life. It was all so bizarre. No one really believed me when I said I was a German pop star called Leo Hurll. I had to produce press cuttings and photos to prove it. Thinkman produced a second album a year later, but by then I was on the verge of my own big break and had a manager who wasn’t inclined to let me go. Leo Hurll left the band under mysterious circumstances. A few German schoolgirls wept into their sauerkraut.

ON THE CIRCUIT

night by night you never knew who you would be working with, so you would check

Time Out

to see who it was going to be. The quality of your evening ahead depended on it. If it was Paul Merton, for example, you knew it would be a laugh. ‘Kissed any men lately?’ he’d ask in mock disgust. Paul was always very willing to help me write new jokes, despite the fact that my innuendoes and music-hall style of performance were a million miles removed from his own carefully honed act. He has a mind that can slide into any comic genre, and year after year he slipped me handfuls of gems that stood out as funnier and cleverer than any of my own offerings. If I wasn’t getting many laughs, I’d race ahead to a ‘Paul’ section, sure in the knowledge that a couple of his lines would get me back on track.

Each year I lured him to my flat where for a couple of French fancies and a cup of tea he’d help me rewrite the audience participation spot. He made sure I laughed from the moment he arrived, delivering a line as I opened the door. Once he came in limping: ‘I tried being homosexual the other night and put me back out.’ On another occasion I opened the door and he said, ‘I’ve followed your career with a bucket and spade.’ We adopted roles with each other, his Hancock to my Grayson. For comedy purposes I was as dismissive of his hetero world as he was horrified by my homo existence. We even went on stage late one night at the Pleasance in the midst of a well-oiled Edinburgh Festival and told alternate lines of our acts, each delivering the other’s punchlines with withering disinterest. For example:

Me: ‘Who does your hair for you?’

Paul: ‘Is it the council?’

Paul: ‘My father always said, “The only bombs you’ve got to worry about are the ones that have got your name on them.” That really upset the neighbours—’