After Tamerlane (37 page)

Authors: John Darwin

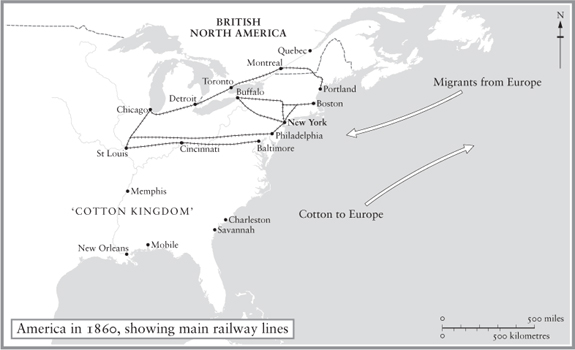

This precocious development in transport and finance helps to explain why so much of the world's trade was conducted between the countries of the West. But there was a third element that helped to make Greater Europe the most commercially dynamic part of the world: the returns on its human capital. After 1830, the trickle of migration out of Europe swelled gradually until by the 1850s it had become a flood. Over 8 million people left Europe between 1850 and 1880, almost all of them for the United States. This great migration had a double effect. It relieved the Old World of the worst of its rural overcrowding and transferred its population surplus to a region where impoverished migrants could become producers and consumers on a larger scale. Secondly, the transmission in human form of Europe's artisan skills (since not all migrants were poor) to an exceptionally benign environment supercharged the growth of what had become by the 1880s the largest economy on the globe.

It was the peculiar pattern of American economic growth that made it such a valuable extension of the European world. The most striking fact about America was its vast reservoir of âfree' land waiting to be exploited by a mobile army of white settlers and (in the South until 1865) their black slaves. The cost of obtaining this land by force or purchase from other claimants (French, Mexicans, Native Americans) was astonishingly low. The returns from agricultural land that had

aeons of âstored fertility' to use up and required only minimal inputs and husbandry (by Eurasian standards) to make it productive were so high that American agricultural productivity even in the 1830 swas 50 per cent greater than Britain's (the home of capital-intensive âhigh' farming) and three times greater than continental Europe's.

31

The rapid takeover of this landed booty poured a stream of exports across the Atlantic and paid for an equal stream of imports. Seventy per cent of American exports went to Europe after 1840; 60 per cent of imports were drawn from there.

32

This trade played a vital part in the growing prosperity of Europe's richest region, its Atlantic fringe. Britain, Europe's richest country, had a larger trade with the United States in 1860 than with the wealthiest countries of either Northern or Western Europe.

33

It was from âAtlantic Europe' (Britain, France, Belgium and the Netherlands) that capital and skills, especially in engineering, were radiated east and south to the rest of the continent.

34

But what made the American âwindfall' so exceptionally beneficial for Europe was the contribution that Americans themselves could make to the speed and scale of their own growth.

In theory, the opening up of such a vast agrarian frontier (land costs aside) required a heavy burden of investment (in transport), a large supply of manufactured goods (both tools and consumer goods) and a sophisticated commercial network to bring credit to the farmer and his goods to market. The economic history of Latin America down to the 1880s showed how slow and uncertain the development of ânew countries' could be. But the story in the United States was entirely different. From the earliest days of independence (indeed, even before it), American commercial life â centred on the ports of Philadelphia, Boston, New York and Charleston â was comparable in sophistication and efficiency to its opposite numbers in Western Europe. After the revolution, as much as before, American merchants maintained very close contact with their trading partners in Britain. They were as adept as their British counterparts in lending and borrowing, and the speculative climate of the new republic may have spread the habit of financial risk-taking even more widely than in the Old World. As a result, of the large amounts of capital needed to build a modern economy (whose land area increased threefold between 1790 and 1850) more than 90 per cent, perhaps 95 per cent, was supplied

by Americans themselves, although foreign capital (mainly British) played a key role in the financing of railways.

35

The emergence of New York as the country's premier port, taking (by 1860) two-thirds of imports and dispatching one-third of exports, created a grand commercial metropolis, the centre of market intelligence and (with the proliferation of banks) financial power. By the eve of the civil war, its population had grown to over 800,000, and began to rival London's in size. With its self-confident mercantile elite â including immigrants like August Belmont, who had excellent overseas connections â its canals and railways stretching far into the interior, and its shipping lines up and down the Atlantic seaboard, New York had the expertise, the information and the resources to use domestic investment to the greatest advantage and gain maximum leverage from its overseas credits. The rise of New York City meant that much of the commercial and financial needs of a large and dynamic economy could be supplied from within.

36

Secondly, for all that its economy was predominantly agrarian, the United States was far from being wholly dependent on Europe for its manufactures. From its beginnings, it had a significant industrial capacity, although much of it was organized in workshops rather than factories until the 1860s. Even in 1830 the United States ranked second (alongside Belgium and Switzerland) in industrial output, behind Britain but ahead of France.

37

By 1850, some 22 per cent of American gross national product came from manufacturing and mining (in Britain the equivalent figure was 34 per cent).

38

The Old Northeast, including New England, New York and Pennsylvania, became an American Lancashire, Yorkshire and Midlands. More and more it could service the demands of the huge agrarian sector (by 1851 Cyrus McCormick was producing a thousand reapers a year in his Chicago factory)

39

and those of a booming population that grew from under 15 million in the 1830s to over 44 million in the 1870s, while drawing relatively less and less on the industrial capacity of Britain and Europe. While British imports from the USA rose by £ 77 million to £ 107million between 1854 and 1880, exports there rose more modestly, from £ 21 million to £ 31 million.

40

It should now be possible to see the importance of America for the larger story of Europe's rise to dominance in Eurasia, and âGreater

Europe's' advance towards global primacy. Conventionally, America has been left out of the narrative of European imperialism in the nineteenth century, entering the stage only in 1898 with the SpanishâAmerican War. In fact America's peculiar growth path was extremely influential. For all the scale of its farming frontier, America's industrial and financial capacity made it a part of the Atlantic âcore' which drove the expansion and integration of Europe. Its trade helped enrich its Atlantic partners, but without consuming too much of their available capital. Its innovations in agricultural, mining, hydraulic and railway technology were readily diffused to other frontiers of European expansion. The telegraph was an American invention. So were three other devices that played a not unimportant part in the European conquest of Afro-Asia: the revolver (invented by Samuel Colt) and the Gatling and Maxim guns. In communications and weaponry, American ingenuity added hugely to the arsenal of Europe's colonizing technique. But perhaps one key aspect of America's economic history was even more decisive.

For almost all the nineteenth century, raw cotton was America's largest export, making up half the total from 1830 to 1860, and as much as a quarter as late as 1913.

41

After 1830, with the rounding-out of the âCotton Kingdom' in Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi, production rose sensationally under the regime of plantation slavery. The cotton trade was the lubricant of the American economy and the secret of New York's commercial ascent. Much the largest market for the cotton crop was Britain, in the mills of Lancashire. Cheap, reliable and abundant supplies of cotton and the invention of power-weaving made Lancashire the textile factory to the world, with a product that was highly competitive in almost every unprotected market. Cotton textiles were the battering ram with which the British first broke into the markets of Asia â though with opium as its steel tip in China. Once the age of plunder had subsided, it was the demand for cotton goods that turned India into a huge economic asset, a captive market that could not be trusted with self-rule lest tariffs follow in its wake. With India in their hands, the British became the greatest military power from Suez to Shanghai, and all round the rim of the Indian Ocean. The âCotton Kingdom' and its slavery system, Lancashire industry and British rule in India were thus bound together by an

extraordinary symbiosis. In this respect, as in so many others, however âanti-colonial' their political views, Americans were the indispensable sleeping partners of Europe's expansion into Afro-Asia.

Its geopolitical, ideological and economic characterstics helped to make Greater Europe a grand expansionist conglomerate after 1830 on a far larger scale than in previous centuries. The voyages of discovery had been sensational. The Europeans' irruption into the trading world of the Indian Ocean was a triumph of naval and military technique. The capture of the mineral-rich states of pre-Columbian America was an astonishing reward for a daring filibuster. The building of an Atlantic economy based on slaves, bullion and the production of sugar had shown how the precocious development of long-distance trade and long-term credit in Atlantic Europe could create a highly profitable annexe to the European economy. But, until the Eurasian Revolution after 1750, none of this had made a decisive difference to the Europeans' influence in the world at large, least of all in the rest of Eurasia. In the Asian seas they had carved out a niche as âmerchant warriors', cruising aggressively along the maritime margins of the Asian states. On land they battered at the gates of the Ottoman and Iranian empires. In almost all of Africa, their direct presence was negligible, even if the commercial and human impact of their slave trade was felt far inland in West Africa, Angola and the Congo basin.

In the age of upheaval after 1750, many of the physical and some of the commercial constraints on European expansion began to give way. Huge new vistas of opportunity were glimpsed in India, China, the Pacific and even tropical Africa, revealed to British audiences by the West African travels of Mungo Park. The Americas, familiar in outline but mysterious in detail, were traversed systematically by Alexander Mackenzie (who crossed modern Canada), by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in their epic journey from modern Pittsburgh to the Pacific Ocean in 1803â6

42

and by the great German geographer Alexander von Humboldt in South America. Enormous intellectual

excitement was generated. Dreams of avarice multiplied. But it was after 1830, and not before, that Europeans began to strengthen their grip on the other continents and pave the way for the global supremacy that seemed theirs for the taking by the 1880s.

This great expansionist drive was fuelled by three sources of energy: cultural, commercial and demographic. As we saw in Chapter 4, the era of the Eurasian Revolution had seen a remarkable florescence not so much in the curiosity of Europeans about the rest of the world as in their apparatus of information-gathering and their marshalling of an intellectual framework into which new knowledge could be fitted. The plausibility of the new universalistic models of social, commercial and cultural progress proffered by (to take only British examples) David Hume, Adam Smith, Jeremy Bentham and James Mill (whose

History of India

appeared in 1817) removed old doubts about the Europeans' ability (and right) to reshape drastically the alien societies into which they had crashed or crept. Even in the late eighteenth century, the early British conquistadors in India had still been overawed by the longevity and sophistication of the subcontinent's cultures. After 1800, this attitude was replaced by a bullish confidence that Indian thought-systems and the social practices they supported were decadent or obsolete, to be ignored or rooted out as circumstances allowed. And behind the new intellectual fervour with which Europeans were prone to denounce the beliefs of non-European peoples was a force which, if not new in European history, was in the throes of a radical revival: missionary Christianity.

By 1830 the missionary had become an active if not ubiquitous agent of European influence, but in some ways a contradictory one. Missionary enterprise in Europe had been rekindled by an emotional reaction against the rationalism of the Enlightenment, the horrific experience of revolutionary war, and (most obviously in Britain) the moral unease awakened by rapid social and economic change. Religious anxiety was sublimated in the evangelical duty to save the heathen by direct action or through the efforts of missionary societies. But, as well as being religious emissaries, missionaries were the eyes and ears of Europe in the African interior, along the China coast (where Charles Gutzlaff was a pioneer evangelist) and in remote New Zealand. Their messages, reports, pleas for help, fund-raising tours,

missionary ânewspapers' and propagandist memoirs goaded opinion at home into action: to raise more money and to press their politicians to intervene or even to annex. Often, as in New Zealand, the motive was to protect a flock of new or promising converts from the predatory activity of degraded Europeans â selling rum or buying sex â or (as in East Africa) against Arab slave-traders. The greatest of all the missionary-publicists was David Livingstone. His heroic status in Victorian Britain showed the enormous appeal of this externalized religiosity.