After Tamerlane (41 page)

Authors: John Darwin

These influences help to explain why London was so tolerant of the Company's imperialism. Perhaps just as telling was the fact that by the 1840s India had become a major asset for a trading empire. By 1850 nearly 12,000 Britons lived in its largest port cities of Calcutta and Bombay.

66

After 1830, British exports to India consistently outstripped those to the British West Indies, the previous jewel of imperial

trade. Indian soldiers were used to force open the ports of China and protect British trade in South East Asia. As the golden eggs piled up, it was easy to forget the health of the goose. But in 1857 the accumulated tensions of empire-building at this frantic pace burst out in a great revolt.

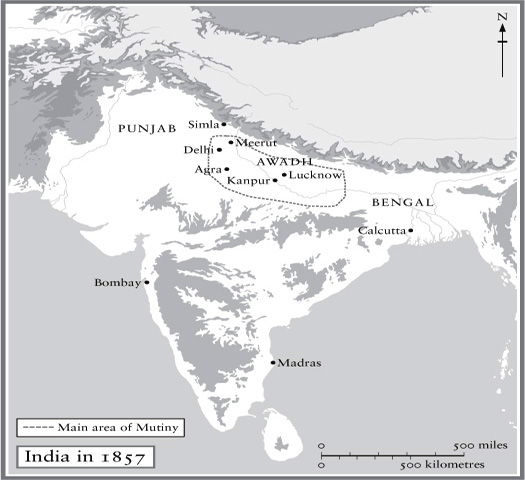

The revolt began as a mutiny of Indian sepoys (soldiers) at Meerut, some forty miles north-east of Delhi, against the use of ammunition defiled by animal fat. Behind this outbreak lay a widespread conspiracy among the Indian officers of the Bengal army. Low pay, the poor quality of the white officers, the decline of plunder, and bitter resentment at the dilution of a high-caste army by low-caste recruits had pushed them towards rebellion. Their aim was to throw off British rule and return to service under Indian rulers.

67

But the rebellion spread with sensational speed because a much larger mass of discontent took heart from the apparent collapse of British military power. Three different kinds of grievance lay behind the wider revolt. Among the Muslim elites of the old Mughal heartland, the declining prestige of the Mughal emperor â a puppet ruler since 1803âwas widely interpreted as a threat to Indian Islam, and the Mutiny became in part a Muslim reaction against an infidel overlord. When the mutineers marched into Delhi in May 1857, they promised the revival of Mughal power. Secondly, for a number of regional magnates, the sudden implosion of British control in the Ganges valley offered the chance to regain the power they had lost â or expected to lose â to the tightening grip of the Company

raj

. This was especially true in the kingdom of Awadh, annexed by the Company the previous year, and among local rulers in the uplands of central India. In Kanpur, power was seized by Nana Sahib, who dreamed of restoring the Maratha confederacy, broken by the Company in 1818. Thirdly, the weight of the Company's land taxation and its efforts to regulate landownership and title worked to the benefit of some local interests but embittered many others. The result was an uneven and unpredictable agrarian revolt. Across a vast swathe of northern India these three elements were jumbled together in an ill-coordinated anti-colonial front.

This was a massive emergency for British rule. The Company faced a long and costly war of reconquest, complicated by external dangers and furious political criticism at home. The Mutiny showed dangerous

signs of spreading among the remaining princely states, whose forces also revolted against their European officers. In practice, although the Mutiny rumbled on into 1859 in the outlying hills and forests, it was

crushed in its heartland in little more than a year. Awadh had been reconquered by July 1858. By April of that year the British had some

90,000

white troops and as many loyal Indians against rebel forces

that were at most 60,000.

68

Despite the scale of their revolt, the rebels were thwarted by four critical weaknesses. The Mutiny was confined to North India: it did not spread (despite some alarming signs) into Bengal, Bombay and Madras, the core regions of British rule. The British could draw troops and supplies from these âloyal' zones and summon help from home. Secondly, the British clung on by their fingertips to some vital outposts in the rebel zone, including Agra and Benares (modern Varanasi), and kept control of their new province of the Punjab (where they were warned by telegraph just in time). The Punjab was vital. From it came the (mainly Indian) army that recaptured Delhi in September 1857, destroying the only credible focus for rebel unity. Thirdly, once the British began to return in force, the divisions among the rebels, and the lack of a common purpose, ideology or leadership, allowed resistance to be broken down district by district. Fourthly, the rebels had too little time before the British counter-attack to smash the Company's network and replace it with their own. No neo-Mughal state could have arisen in North India: the rebel governments in Delhi and Lucknow could not even pay their sepoys. Though many Indian notables threw in their lot with the rebels when the British vanished, they had too much to lose to struggle hard when they reappeared. The uncompromising ferocity of the British reconquest, visible in the sack of Delhi and the expulsion of its Muslims, left no room for political compromise.

69

Yet there was no doubt that the shock of the Mutiny profoundly affected Britons' views of their Indian empire. They were taken completely by surprise. The revolt had spread with electric speed. Hundreds of whites had been killed, including a large number of women and children (more than 200 in the Kanpur massacre). Despite innumerable acts of loyalty and humanity by Indians, a miasma of mistrust inevitably soured Anglo-Indian relations. Race feeling became more virulent. Many British were convinced that the source of the Mutiny was a Muslim conspiracy: âThe sepoys are merely tools in the hands of the Mussulmans.'

70

It became fashionable to argue that British rule depended on the sword.

71

Thereafter, mutiny scares were never far from the official mind. British rule became more cautious and conservative. The imperial burden of guarding India against attack from within and without seemed heavier. But there were mass

ive compensations. After 1860, with the spread of railways, India developed much more rapidly as a source of raw materials and the greatest market for Britain's greatest export, cotton textiles. And if the burden of garrisoning India was heavy, it cost the British taxpayer nothing. Indeed, after 1860 two-thirds of the standing army of the British Empire (a total of some

330,000

British and Indian soldiers) was a charge on Indian not British revenues, and the forces in India could be (and were) used everywhere from Malta to Shanghai. As the partition of Afro-Asia speeded up after 1880, India's geopolitical, as well as its economic, value became an axiom of British policy. An uncertain empire had become indispensable.

What had happened in India was a warning, if warning were needed, of what could follow elsewhere in Eurasia and Africa once the Europeans arrived in the neighbourhood with their range of new weapons â commercial, cultural and military. More or less consciously, the rulers and elites of the Afro-Asian world found themselves in a race. They had to find ways of binding together their often loose-knit states; to reinforce the feeling of cultural cohesion; to encourage more trade and extract more revenue. And they had to do so in time. Again and again they faced a dilemma. If they tried to âself-strengthen' using âEuropean' methods â European-type armies, bureaucracies, schools and technologies â they ran a huge risk. The social cohesion that they desperately wanted might dissolve in disputes with the old guardians of culture: the teachers, clerics, and men of letters and learning. The drive for political unity might affront existing power-holders who relished their provincial autonomy. More regulation of trade might enrage the merchants and also their customers. If they let more Europeans in, as traders, advisers and experts, they might suffer a backlash, bringing accusations of weakness or even betrayal. Nor could they be sure that these licensed invaders would not do them harm and be a source of disruption. But if they tried to exclude them, the self-strengthening project might run out of steam. Worse still, they might provoke an attack before they were ready, and bring on a catastrophe.

They had to run two races at once: a race to self-strengthen before Europe arrived in force; and a race to âreform' before internal dissent wrecked all hope of success.

Of the great Eurasian states beyond Europe, China (above all) and Japan had always been the richest, strongest and least accessible to European influence. Until the 1830s, they seemed almost invulnerable to European attack. By 1840 that old immunity was dead in the case of China and dying in Japan. Instead, both states came under growing pressure from the Europeans. Britain, Russia and the United States took the lead. They demanded free access to the ports of East Asia, freedom to trade with Chinese and Japanese merchants, and an end to the diplomatic protocols under which Westerners had the status of barbarians, culturally and politically inferior to the Middle Kingdom and Japan. They accompanied these demands by the demonstration and use of military force, and by territorial demands â coastal and modest (though far from trivial) by the maritime British, much larger by continental Russia. Not surprisingly, this traumatic alteration in their international position had far-reaching political, cultural and economic consequences in China and Japan. By 1880, both had undergone a series of internal changes that were revealingly described by their makers as ârestorations': the T'ung-chih (âUnion for Order') restoration in China, the Meiji (âEnlightened rule') restoration in Japan.

72

Both were the result of the convergence of internal stresses and external threat. But, as we shall see, their trajectories were very different, and so was the scale of the transformation they promised.

China was the first to feel the weight of European displeasure. The occasion was the breakdown of the old âCanton system' for China's trade with Europe. Under this system, Canton was the only port through which the trade â confined to a closely regulated guild of Chinese merchants (the âHong') â was lawful. Europeans (who were allowed to maintain warehouses â âfactories' â on the quay) were forbidden to live permanently in the city, departing for Macao at the close of the trading season. The end of the East India Company monopoly of British trade in 1833, and the rapid increase in the number of âfree' British merchants selling opium â almost the only commodity that the Chinese would accept for their tea, apart from silver â brought on a crisis. When the Chinese authorities, alarmed by

the flood of opium imports and the outflow of silver (the basis of China's currency) to pay for them, as well as by the widespread flouting of the rule that all foreign commerce must pass through Canton, tried to reimpose control, driving away the British official sent to supervise the trade and confiscating contraband opium, the uproar in London led to military action. In February 1841 the Royal Navy arrived off Canton, the Chinese war fleet was destroyed, and an invading force landed in the city. When the Chinese prevaricated, a second force entered the Yangtze delta, occupied Shanghai, smashed a Manchu army, and closed the river and the Grand Canal (the main artery of China's internal trade). By August 1842 the British had arrived at Nanking, the southern capital of the empire, and prepared to attack it. The emperor capitulated, and the first of the âunequal treaties' was signed.

73

Under the 1842 Treaty of Nanking, five âtreaty ports' were opened to Western trade, Hong Kong island was ceded to the British, the Europeans were allowed to station consuls in the open ports, and the old Canton system was replaced by the freedom to trade and the promise that no more than 5 per cent duty would be charged on foreign imports. It was a staggering reversal of the old terms on which China had dealt with the West. But its significance (at this stage) should not be overstated. Irksome as the treaty was to the Chinese authorities, it had certain merits. The foreigners were kept well away from Peking, could not travel freely, and, under the system of consular jurisdiction, would be carefully segregated administratively from the Chinese population.

74

To a great inland, agrarian empire, the snapping of barbarians on the distant coast was a nuisance to be neutralized by skilful diplomacy.

But the treaty was not the end of the matter. It was followed by continual friction between Chinese and Europeans. By 1854 the British were pressing hard for its revision, to open more ports and allow Europeans to move freely into the interior and widen the scope of their trade. In 1856, the â

Arrow

' incident, when the Chinese seized a ship allegedly flying the British flag, became the excuse for a second round of military coercion. When the Chinese stalled the implementation of a new treaty agreed in 1858, an Anglo-French expedition arrived at Tientsin and marched on Peking, burning the emperor's

summer palace in revenge for their losses. The second great treaty settlement, the Convention of Peking, threw open many more ports, as far north as Tientsin and far up the Yangtze, and gave Europeans (including missionaries) the right to roam in the Chinese interior. Moreover, the old fiction of Chinese diplomatic superiority was to be firmly scotched by forcing the emperor to permit European diplomats to be stationed in Peking. China, it seemed, had been forcibly integrated into the Europeans' international system, on humiliating terms and as a second-rate power, at best.