After Tamerlane (44 page)

Authors: John Darwin

By 1880 the benefits of this great effort at reform seemed meagre, and the costs prohibitive. In 1878 the empire suffered a devastating series of territorial losses. Almost all the European provinces where there were substantial numbers of Christians were ripped from its grasp. Wallachia and Moldavia, autonomous since the 1820s, became independent Romania. The province of Nish was added to Serbia. Bulgaria became autonomous, and was allowed to merge with its southern third, so-called Eastern Roumelia, a few years later. Tiny Montenegro became a sovereign state. Even Bosnia and Herzegovina, where there were many Muslims, were placed under Habsburg tutelage. To add to these injuries, the island of Cyprus, Ottoman since 1571, was occupied, though not formally annexed, by the British, as the price of their support against Russia, while Russia seized the districts of Kars and Ardahan in eastern Anatolia. Before this territorial catastrophe, the Ottoman government had already been forced to concede a special regime under foreign surveillance in the Christian district in the Lebanon (âThe Mountain') and in Crete, where an uprising of Greek-speaking Christians had raged between 1866 and 1869. And not long after it, Egypt and Tunis, both technically under Ottoman rule, were occupied by the British (who took Egypt in 1882) and the French. Nor was the great crisis of the 1870s solely political. Its effects had been worsened by financial disaster. In 1875 the Ottoman government defaulted on its foreign loans and became bankrupt. The price of its return to financial respectability was acceptance of a draconian regime of inspection and control. After 1881, the Ottoman Public Debt Administration, staffed and supervised by European bankers and officials, had first claim on Ottoman revenues to repay the creditors, doling out the residue to the sultan's government. Materially and symbolically, it seemed, the empire had been reduced to a virtual dependency.

On the face of it, the

Tanzimat

had led not to self-strengthening, but to self-mutilation or worse. In reality, the

Tanzimat

reformers

had faced a combination of internal and external pressures far more daunting than those confronting their counterparts in East Asia. Strategically, the Ottomans were desperately vulnerable to the military power of Russia â unless the tsar could be restrained by his European rivals â and their position was made all the worse by the drastic decline of their naval power.

104

It was the Russian invasion in 1877 that led to the territorial losses at the Congress of Berlin in 1878. But the underlying weakness was the rejection of Ottoman rule by the Christian minorities and their insistent appeal to the European states to intervene on their behalf. As the century wore on, this problem became more and more acute. The spread of the ânational idea' through the rest of Europe was bound to infect the Ottoman minorities, who maintained close contact with their ethnic brothers outside the empire. Economic change, from which Greek merchants (for example) profited more than their Muslim fellow subjects, created a larger and more articulate constituency for political rights and tended to undermine the higher clergy through whom the sultan had ruled the Christian millets. Identity, said these new ânationalists', must be sought in territorial statehood rather than church membership. Tanzima

t

reform itself had brought greater reliance on educated Christians. In these conditions, the reformers' hope that Christians would accept a shared Ottoman or âOsmanli' citizenship and sink their differences in common loyalty to the sultan was unlikely to be realized. Indeed, when Midhat Pasha tried out this programme in Bulgaria in the 1860s he found himself attacked from all sides.

105

To many Muslims, the dilution of the empire's Islamic character was deeply offensive. It meant sidelining the ulama, the local scholar class, the repositories of legal and theological expertise. It meant shifting the empire's foundations from the bedrock of Muslim loyalty to the shifting sands of Christian cooperation. Anti-reform feeling was sharpened by resentment against the

Tanzimat

's bureaucratic centralization, and by outrage at the fate of the hundreds of thousands of Muslim refugees driven out of the Caucasus by the Russians.

106

Indeed, the settlement of these refugees in the Ottoman provinces seems likely to have raised the temperature of ethnic and religious antagonism to fever pitch in the 1870s.

Conceivably, a powerful and well-financed administration might have won the battle for local control and deterred its foreign enemies

more forcefully. But on this front, too, the reformers were defeated. They were driven into foreign borrowing by the soaring costs of the Crimean War (1854â6), and then badly mismanaged their loan operations. By the 1870s, the annual charge on these loans amounted to some two-thirds of state revenues, and on some borrowing they were paying up to 30 per cent interest a year.

107

Although they increased their revenue by some 50 per cent, they failed to drive out the old practice of tax-farming and control collection directly. They gambled on the growth of trade to fill the state's coffers, but Ottoman trade increased much less than the global average,

108

while political turbulence damaged both Ottoman commerce and the empire's credit rating. State-led efforts at industrialization languished, and the export of raw materials encouraged enclave development round the ports â a tendency that was reinforced by poor inland communications.

109

Hardly any of the government's borrowing found its way into the building of infrastructure like railways. The contrast with Meiji Japan could hardly be more striking. Ethnic diversity and the lack of a samurai-like caste to maintain social and political order was compounded by a pattern of economic development in which foreign control became âoverwhelming'.

110

Yet, despite the pounding it had taken, the Ottoman Empire did not fall to pieces or slide weakly under European rule. The loss of the bulk of its European provinces made the empire much more fully a Turkish, Arab and Muslim state. Under the sultan Abdul Hamid II (r. 1876â1909), Ottoman rule became more sympathetic to pan-Islamic movements and more conscious of its international role as the guardian of the holy places, to which an ever-growing stream of Islamic pilgrims was brought by steamship and railway from India and South East Asia. At the same time, the old programme of the

Tanzimat

was pressed forward. The state machine was slowly modernized. The railway network was enlarged. Military and administrative control was pushed deeper into the Arab provinces. The Ottomans had lost the struggle to keep the great multi-ethnic empire they had built in the sixteenth century. After 1880 they entered a new race to solidify their remaining territories before a further confrontation with Europe, or the growth of an Arab nationalism, could tear Abdul Hamid's empire to pieces.

*

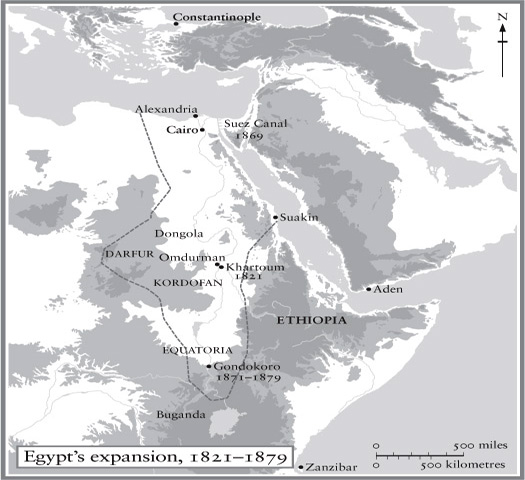

Two other Middle Eastern states were also drawn into the race against time. Their fates would be different. The first was Egypt, formally still part of the Ottoman Empire. Under its Ottoman governor Mehemet Ali, sent by the sultan after the expulsion of its French invaders, the practical autonomy of the Mamluk era became more definite. Mehemet Ali constructed an authoritarian state around his new army.

111

His real ambition was to build an Egyptian empire from the Sudan to Syria, and to make himself master of the Arab lands. Twice he came close to unseating the sultan; twice he was thwarted by the European powers. Instead he was forced to open his border to European trade, and give up his costly experiment in state-managed manufactures. Mehemet Ali died in 1849, but under his successors Said (r.1854â63) and Ismail (r. 1863â79) part at least of his grand design was pushed steadily forward.

For both these rulers, the ultimate aim was to win for their dynasty a formal equality with the Ottoman sultan, and sovereign independence, free from the claim of the Ottoman government to control foreign relations, determine the size of their army, or (in the very worst case, which actually happened in 1879) to dismiss them from office. Both had in mind not a ânation' state but a monarchical state, in which the ruler's power was paramount. The âTurko-Circassian' elite (a mixture of the old Mamluk ruling class and Mehemet Ali's Turkish and Albanian followers) would be made to pay for its privileged status in an overwhelmingly âArab' society by loyal support for its patron and protector. Both rulers understood that their chances depended upon a rapid increase in agrarian wealth.

The omens were favourable. The demand for Egypt's long-staple cotton in industrial Europe seemed almost insatiable, but to meet it required an agricultural revolution. The area of cultivable land grew by 60 per cent between 1813 and 1877.

112

The delta marshlands below Cairo were drained and cleared. Perennial irrigation, supplied by a network of canals and barrages, replaced the reliance on the annual flood, and doubled production. By the mid-1860s foreign investment was growing, and foreign-owned banks sprang up to serve the new landed class. Alexandria boomed as the Mediterranean port city of the export economy. Railways were built. A European-style quarter was laid out in Cairo alongside the Nile, with a new royal palace, a

stock exchange, an opera house, and sweeping boulevards on the Parisian pattern.

113

With its centralized bureaucracy, landowning elite, liberal property laws, and large foreign community (

100,000

strong by the 1870s: by contrast, the number in Iran was much less than a thousand), Egypt seemed the model of a âdevelopment' state, a triumph of reform, an Islamic Japan. It attracted the service of adventurous Europeans â like Charles âChinese' Gordon (the later Gordon âof Khartoum'), sent to rule the Sudan and extirpate slavery (what better proof of the ruler's modernity?). By the 1870s, full independence seemed only a matter of time. Perhaps it would come by default in the next great crisis in Ottoman fortunes. Meanwhile Ismail (who had obtained the more dignified title of âkhedive' in 1867) was flatteringly described in an authoritative guide to the country: âHis Highness speaks French like a Parisian⦠Be you engineer, merchant, journalist, politician, practical agriculturalist, or almost no matter what else, you will soon feel that you have met your match in special intelligence and information.'

114

For Said and Ismail, the Suez Canal was meant to crown their achievements.

115

The costs would be high, but the pay-off tremendous. Its income would bring them a new stream of wealth. Its Nile connection (the Sweetwater Canal) would bring a new tract of land into intense cultivation. It promised above all a huge geopolitical dividend. Once the ruler of Egypt had become the guardian of the world's most valuable seaway, the great powers of Europe would acknowledge the need to protect him against any threat of aggression, and would see the point of his independence. It was no wonder that Said was persuaded to take a large share in the company launched by de Lesseps to build the canal. When cotton prices soared up in the 1860s (when the American South was cut off by blockade and then wrecked by invasion), it was easy for Ismail to borrow in Europe until the national debt reached £ 100million. But as the cotton price sank in the mid 1870s, and before the canal (opened in 1869) could show a return, speculative boom turned to financial bust. In 1875 Ismail had to sell his canal shares to the British government for £ 4 million â perhaps a quarter of their value. A year later he â and Egypt â was bankrupt.

Now the full price of the race against time began to be paid. The frantic change in Egypt's social order had piled up resentments. The

landowning class was eager to check the authoritarian style of the ruler. The ulam

a

(whose headquarters at al-Azhar in Cairo â part mosque, part university â was the most prestigious centre of learning

in the Islamic world) disliked the ruler's embrace of foreign infidel practices, his web of corruption, and his extravagant lifestyle. In the army and bureaucracy, the Arabic-educated class loathed the

continued domination of the Turko-Circassian elite, restored to favour by Ismail after Said's flirtation with a more âArabic' policy. All these unresolved conflicts were charged with a sense of social malaise: fear and suspicion of European carpetbaggers; moral unease at the gross exploitation of the fellahin (rural cultivators) class, the principal victims of agrarian change.

116

The mood of revolt now had a new voice in the journalists and newspapers that began to appear. Thus the external crisis over foreign debts (and Europe's demand for effective control over Egypt's finances) quickly turned into a crisis at home over who would bear the real burden of the foreign demands. The Suez Canal â the booster rocket towards full independence â became the Trojan Horse of foreign control, and (quite literally) the invasion route for alien rule.

Iran was more fortunate, and its rulers less bold. They had anyway much less room for manoeuvre. Mehemet Ali had founded his state on the power of his army and the wealth to be gained by the export of cotton. The Qajar rulers, who entrenched their power at much the same time, lacked these resources. Creating an army that would deter external aggressors and internal dissent was far more difficult: indeed, they had to make do with an imperial bodyguard of

4,000

men.

117

The shahs faced the antipathy of the clerical elite â the Shi'a

ulama

â whose social power was much greater than that of the

ulama

in Egypt.

118

They had to base their authority to a crucial degree on an alliance of tribes, since pastoral nomads made up more than a third (and perhapseven half) of thewhole population, and formeda massof armies in being. They had no bank of ânew' land with which to reward a compliant elite or finance a larger bureaucracy. And, although the Iranian economy staged a major recovery from the chaos and disorder of the late eighteenth century, there was no bonanza from cotton to draw in foreign investment or pay for a programme of public improvements in irrigation, railways or roads. The country remained in a stage of acute localization, in which tribe and sub-tribe, village community, artisan guild, urban quarter or ward, sect, religion or language remained the main source of identity and the main cause of division. In short, the means to build a strong dynastic state upon the Egyptian model were almost entirely lacking.