After Tamerlane (46 page)

Authors: John Darwin

It was this combination of a âglobalizing' world and the weakness or decay of non-European states that excited and alarmed contemporary opinion â of all races and cultures. It helps to explain the sense of urgency with which European politicians, diplomats, merchants, settlers and missionaries debated their âimperial' futures. Their expectations were fashioned by three different scenarios. The world as a âsingle system', bound ever more closely by the iron links of its railways and the invisible bonds of finance and commerce, was a vista of plenty. Trade would expand; investment would flourish; more land would be brought into commercial production. The sphere of European influence â not least its religious influence â would grow in proportion. It was little wonder that a rash of speculative enterprise broke out and special-interest lobbies appeared: to raise cash, make publicity, and press their governments for help. In the new world economy, there were fortunes to be made. But the second scenario was less reassuring. Accompanying the sense of an accessible world, no longer protected by the moat of distance, was the pervasive fear that it was âfilling up' fast. In 1893 the young American historian Frederick Jackson Turner famously declared that America's open frontier had been closed, and he was quickly followed by similar warnings in Australia and New Zealand.

3

With no âempty lands' in the temperate world to absorb their energies, the Europeans would compete for control of the tropics and the lands and commerce of the âdying nations'.

4

Here, where local order was weak, a forceful foreign presence would be all. A treaty, a railway, a bank or a base would create a virtual protectorate, a diplomatic client, an exclusive zone of trade. Opportunism and vigilance were the price of survival in this coming world order. But the result would be an ever-fiercer rivalry between the European powers, and the growing risk that they would come to blows.

There was a third scenario, and a third set of anxieties. To Japanese, Chinese, Indian, Middle Eastern and African observers, the danger seemed to lie in the arrogant ease with which European interference could wreck their social cohesion and cultural self-confidence. The

more accessible their states were to European travel and trade, the easier it became for foreign interests and influence to rush their defences, insert newforeign enclaves, and subvert local authority. Even in East Asia it was easy to imagine a not-distant future in which Western trade, sea power, bases, treaty ports and missionaries had segmented the region, disrupted its culture, and parcelled it up for conquest at leisure. The world had grown small, said the Japanese historian and expert on China Naito Konan. Europe and America had surrounded East Asia, and a racial struggle was coming.

5

Among Euro-Americans, the prospect of closer socio-economic relations with large Afro-Asian societies produced a different kind of disquiet. The Europeans might be masters of the universe. But their drastic encroachment upon more âbackward' peoples had created a âcrisis in the history of the world' noted the historian-turned-politician James Bryce.

6

âFor economic purposes,' he thought, âall mankind is fast becoming one people' in which the âbackward nations' would be reduced to an unskilled proletariat. It would not be easy to avoid the ârace antagonism' that would follow, since intermarriage (the best cure) was disliked by the whites.

7

In his highly influential book

Social Evolution

(1894), Benjamin Kidd (who combined social research with his career as a taxman) warned that Europeans could maintain their predominant position only by the arduous pursuit of âsocial efficiency', since neither colour, descent nor intellectual ability was the key to their primacy. The mobility of labour in the newglobal economy was another source of worry. Fear of a flood of cheap Japanese, Chinese, Indian and African labour bred paranoid fantasies of a stealth invasion in many settler countries: in Canada, the Pacific states of America, Australia, NewZealand and South Africa.

Thus triumphalist predictions of Europe's global supremacy had a much gloomier accompaniment. Segregation would be needed to prevent persistent race friction; systematic exclusion (as in the âWhite Australia' policy) to keep non-whites from swamping the temperate âwhite man's countries'; and stringent control over new subject peoples, lest the sign of weakness provoked a revolt. Even so, mused Charles Pearson in his

National Life and Character

(1893), a reversal of fortune was still on the cards. Once all the temperate lands had been filled, and there were no further outlets for Europe's population

surplus, he argued, economic stagnation was bound to set in. And, since the âlower races' would increase in number much faster than the âhigher', Europe's hour of triumph was bound to be brief. âThe day will come, and perhaps is not far distant', he warned his readers,

when the European observer will look round to see the globe girdled with a continuous zone of the black and yellowraces, no longer too weak for aggression or under tutelage, but independent, or practically so, in government, monopolizing the trade of their own regions, and circumscribing the industry of the European; when Chinamen and the nations of Hindostan, the states of Central and South America, by that time predominantly Indian, and⦠the African nations of the Congo and the Zambesi, under a dominant caste of foreign rulers, are represented by fleets in the European seas invited to international conferences, and welcomed as allies in the quarrels of the civilized world⦠We shall wake to find ourselves elbowed and hustled, and perhaps even thrust aside by peoples whom we looked down upon as servile, and thought of as bound always to minister to our need. The solitary consolation will be, that the changes have been inevitable.

8

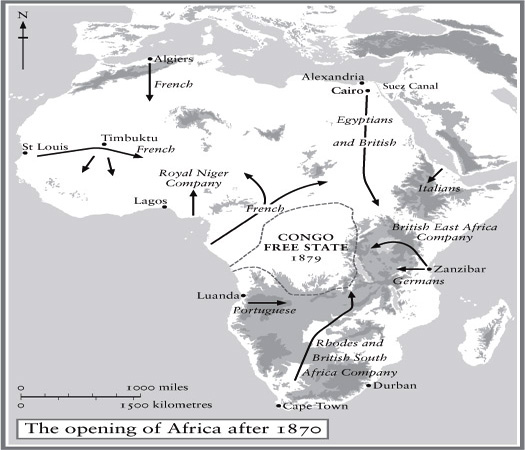

The scaling-up of the Europeans' intrusive power after 1880 was a worldwide phenomenon. But nowhere else was their imperial expansion so dizzyingly swift or so astonishingly complete as in sub-Saharan Africa â the âdark continent', whose interior Europeans had been noticeably slowto claim. This is why the African case has so fascinated historians. More than a century later, the âscramble' for Africa in the 1880s and the continent's âpartition' and âconquest' evoke strong emotions and uneasy debate. This is partly because they offend contemporary notions of racial justice, and partly because Africa's postcolonial condition has made its colonial past seem more painfully real than has been the case in more fortunate regions. The drama and violence of Europe's takeover of Africa has also encouraged the idea that it was the âclassic' case of European imperialism. In fact tropical Africa was no more typical of European expansion than was the

commercial imperialism practised in Latin America and China, the settler imperialisms of North America and Australasia, or the imperialism of rule fashioned by the British in the Indian subcontinent. Compared with the contest for imperial power across the vast tracts of Eurasia, Africa was a sideshow. But the African case does allow us to see with greater clarity than elsewhere some of the geopolitical conditions that favoured European primacy after 1870. It may also prompt us to ask why African societies were so much more vulnerable to external disruption (once Europeans had the will and the means to inflict it) than most of their counterparts in Asia.

What impelled the Europeans' great leap forward in Africa? Its origins lie in the gradual application to this least accessible continent of the means of entry already used elsewhere. The steamship and railway were the battering rams with which European traders could break the monopolies that African coastal elites and their inland allies had tried to maintain over their commercial hinterlands. In the west, the east and the south, the 1870s were a time when the Europeans were laying plans to push their operations deeper. Nor were they alone. Egyptians (in the south of modern Sudan) and Zanzibaris (in the Great Lakes region) also hoped to carve out newcommercial empires. What made these ventures seem practical (and potentially profitable) was not just a convenient new transport technology. Three other factors were also at work. The first was the way in which the commercial âtrunk routes' around the African coast were becoming steadily busier â reducing the cost of connecting its trade to the main global circuits. This was particularly obvious in East Africa, where the Suez Canal and the much heavier traffic between Europe and Asia brought a commercial revolution to the Indian Ocean and the East African coast.

9

But it also applied in the west and the south. The second great factor was the supply of cash. By the 1870s the development of Europe's financial machinery (especially in London) was making it far easier than before to raise the sums needed to push a speculative advance into little-known terrain. The habit of foreign investment was becoming more deeply ingrained and more widely practised among Europe's propertied classes. The black arts of âboosterism' â commercial propaganda, company promotion and insider dealing â enjoyed a heyday of freedom to talk up the prospects of the

most unlikely eldorados and gull the greedy and innocent. Thirdly, what helped to give substance to these dreams of wealth was the actual fact of a mineral bonanza in parts of Africa. By the 1870s both diamonds and gold had been found in South Africa, a prelude to the great gold rush of the 1880s. This attracted a stream of speculative capital into the search for gold ever further north. Once Cecil Rhodes and his friends won control of the Kimberley diamond fields for their newconglomerate, De Beers Consolidated, they used its profits to fund the great filibustering expedition that turned modern Zimbabwe and Zambia into a huge private empire, the domain of their âBritish South Africa Company'.

10

Many at home were eager to buy into Rhodes's grand enterprise.

But this is only a part of the story. The piecemeal invasion by European private interests â some commercial, some part philanthropic â and the careerist activism of officials and soldiers on the edge of the existing colonial zones would have created a slow-moving frontier of influence and authority. It would have been an untidy process. Failed advances, furious commercial rivalry, bankrupt ventures, acts of resistance and frontier wars would have delayed the progress of European occupation and made it far slower than the conquest of North America â if only because the demographic weight of the European incomers was infinitely smaller. But this was

not

the pattern of the African scramble. This was exceptionally rapid and (in cartographical terms) extraordinarily complete. Above all, it was a process in which European governments took an active part â if only by agreeing on the terms of the share-out, and accepting the obligation to impose their rule. The localized activity of European frontiersmen was suddenly caught up in a vast diplomatic arrangement. Why did this happen?

Much of the answer lies in the knock-on effects of events unfolding elsewhere. The 1870s were a time of crisis in several of the great non-European states spread across Eurasia, but nowhere more than in the Ottoman Empire, whose financial strains we have already noted. Between 1875 and 1881 this empire was in turmoil. It went bankrupt. It was invaded. Its territories were cut down in the peace conference that followed. For several years, even its survival was in doubt. Its

bankruptcy (in 1875) helped to drag down its nominal dependency, the khedivate (or viceroyalty) of Egypt, whose go-ahead dynasty had tried to modernize the country with almost reckless haste around the grand centrepiece of the Suez Canal â one of the greatest engineering achievements of the nineteenth century. The ruler in Cairo had borrowed deeply from European lenders. But when his revenues

sagged in the mid- 1870s they refused to lend more, and without a flowof newcash the Cairo government defaulted.

11

The Egyptian khedive Ismail dared not abandon his European creditors. He may well have feared that their governments would intervene. But he was also anxious, sooner or later, to resume the modernizing programme on which his dynasty was built. So he agreed to appoint two European watchdogs to supervise his finances and claw them back to solvency. It was a risky experiment. It was bound to annoy those who would suffer from the cuts. It would be resented by his officials and ministers. It would weaken his prestige. And it would rouse suspicion in a Muslim country (the site of Islam's greatest centre of learning was at al-Azhar) of an infidel plot to take political power. It was hardly surprising that the watchdogs soon found that their âreforms' were ignored. Their complaints encouraged the governments in London and Paris to demand a tougher regime, the so-called âDual Control', on which their eye would be closer. But the main result was to provoke the growth of a popular national movement against foreign interference and against the authoritarian powers of the khedive as well. When the Dual Control tried to cut down the army, a revolt broke out in 1881 under a charismatic officer, Colonel Arabi.