After Tamerlane (42 page)

Authors: John Darwin

To the more thoughtful of Chinese administrators and scholars (and Chinese officialdom was recruited from the ablest classical scholars), these startling events required explanation. Their conclusions were uncompromising. Their methods had failed: urgent reform was needed. Better ways had to be found to deal with the barbarians. Western knowledge would have to be systematically translated and disseminated. Transport and communications must be improved. Above all, China must acquire the modern weapons needed to prevent the ability of the West to attack the vital points of the empire almost at will. âWe are shamefully humiliated by [Russia, America, France and England],' complained the scholar reformer Feng Kuei-fen (1809â74), ânot because our climate, soil, or resources are inferior to theirs, but because our people are really inferior⦠Why are they [the Westerners] small and yet strong? Why are we large and yet weak?'

75

But, by the time that Feng wrote, the empire was beset by an internal crisis that seemed far more dangerous than the spasmodic coercion inflicted by the Europeans. In the 1850s and '60s, huge areas of central and southern China, some of its richest and most productive regions, were in the grip of rebellion, paralysing trade, cutting off the imperial revenue, and portending the withdrawal of the âmandate of heaven': the source of dynastic legitimacy.

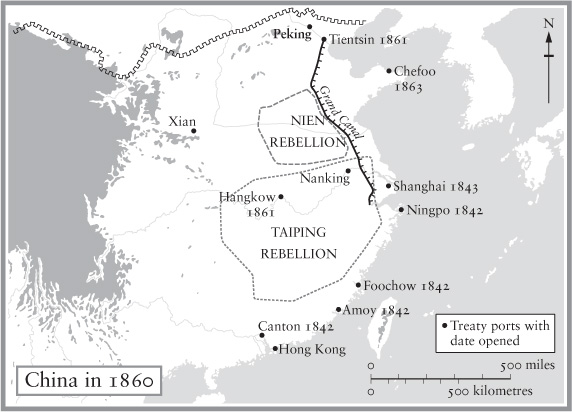

Much the most serious of these great upheavals was the Taiping Rebellion. It began in South West China with the visions of a millenarian prophet, whose preaching combined elements of Christian teaching picked up from the missionaries with the bitter outcry of peasantry oppressed by economic misfortune. Hung Hsiu-ch'uan declared himself the younger brother of Jesus Christ, and in 1851 proclaimed a new dynasty, the Taiping T'ien-kuo, or Heavenly King

dom of Great Peace, with himself as Heavenly King. With astonishing speed, his movement gathered recruits into a peasant army, picked off the isolated garrisons of the Ch'ing government, and swept into the empire's Yangtze heartland. By early 1853 it had captured Nanking. Hung's aim, however, was to replace the dynasty. By 1855 his troops had reached Tientsin and seemed poised to capture the ultimate prize, the imperial capital. This was the high tide. From there his army was forced gradually back to the Yangtze valley, but its eventual defeat was delayed until 1864, with the death of Hung and the fall of Nanking to imperial troops.

76

The Taiping Rebellion, the great Nien Rebellion that spread across a vast region north of the Yangtze and lasted until 1868,

77

and the Muslim revolt in the west (1862â73) were symptomatic of a drastic breakdown in the political, social and economic order. This may have had its roots in the plight of the agrarian economy, which was battered by a series of misfortunes after 1830. China had achieved a remarkable growth in agricultural production in the eighteenth century. The clearing of new land, and the more intensive farming of old, had kept food supplies well abreast of a surging population that had reached

c

. 430million by 1850. Commercialization and the rise of internal trade enabled farmers to increase their output by specialization and exchange. Increasing supplies of silver (as foreign trade expanded) lubricated this prosperous pre-industrial economy with a stream of money.

78

But well before 1850 these sources of economic expansion had dried up. The inflow of silver was replaced by a massive outflow, as opium imports soared:

79

perhaps up to half of the silver accumulated since 1700 was lost in a few years after 1820.

80

The sharp contraction of money supply forced down prices and dried up commerce. The supply of new land could no longer meet the pressure of population. The struggle to extract even more food from old lands reached its limit and may have triggered an ecological backlash, with deforestation, soil erosion, the silting of rivers and declining fertility. In north-central China, the shift in the course of the Yellow River in 1855 was an environmental disaster on a massive scale. With these multiple setbacks came rising social tension: between tax-collectors and payers; between landlords and tenants; between locals and newcomers in regions where earlier prosperity had drawn in people from

elsewhere; between ethnic and religious minorities and the Han majority, who had poured into the western lands in the colonization movement of the previous century. The state officials, who struggled to keep order, collect the land revenue, maintain the waterways and manage the grain reserves, faced increasing resistance from a discontented population. Their authority and prestige had already been

undermined by the âprivatizations' in the era of commercial expansion as licensed merchants took more control over tax-collecting, water conservancy and the grain tribute system â a change that was readily equated with the growth of bureaucratic corruption. It was no accident that the Taiping programme demanded more land for the peasants, and the return to a more frugal and self-sufficient age. Nor that it denounced the use of opium â a stance that ensured the furious hostility of Western merchants and their governments.

By 1860, then, the scholar-gentry officials who governed the Ch'ing Empire faced disaster. Their prestige and self-confidence were being

hammered by the demands of the British, French, Americans and Russians (who had wrung the vast Amur basin out of Peking in the Treaty of Aigun in 1858). Their domestic authority, and the revenue base that sustained the whole superstructure of imperial rule, were imploding as rebellion spread across the eighteen provinces of China proper as well as the outer provinces. In these desperate conditions, their achievements were remarkable. New generals like Tseng Kuo-fan (1811â72) and Li Hung-chang (1823â1901) contained, squeezed and eventually suffocated the great rebellions. They raised new-style armies in the provinces, equipped with Western weapons. They mobilized the provincial gentry, who officered these new regional forces. They levied new taxes on commerce and foreign trade (through the Western-managed Maritime Customs Service). As the rebellions petered out, Tseng and Li looked for ways to âself-strengthen' China. They encouraged the import of scientific knowledge. Two great arsenals were built to produce modern weapons. Chinese merchants were encouraged with subsidies and monopolies to invest in modern enterprises, especially shipping and mining. There was even an abortive attempt to buy a modern navy in the West, complete with European officers. These âmodernizing' efforts were accompanied in rural China by the drive to resettle land devastated by the rebellions, repair the waterways, and restore the

authority of the gentry officials.

81

What this great effort could not achieve (and was not meant to achieve) was the transformation of China into a modern state on the Western model. The limits of Tseng's and Li's âself-strengthening' were humiliatingly revealed in August 1884, when French warships blew China's new (but wooden-hulled) fleet to pieces in a quarrel over Vietnam.

82

Though stateâmerchant cooperation might have found ways of promoting industrial enterprise, this was a far cry from industrializing the economy more generally. The mid-century combination of agrarian crisis and political upheaval made the task even harder. There was no prospect, for example, of building a new China round the core of its most prosperous region in the Yangtze delta, the heart of its eighteenth-century commercial economy. It had been badly damaged in the Taiping Rebellion, and was too vulnerable to Western penetration to serve this purpose. It might even be argued that the real priority of the ârestoration' was precisely that: to restore the authority of the Confucian state and its ethos of frugality and social discipline, not to break the Confucian mould.

83

But if industrial transformation had eluded the scholar-gentry reformers, the importance of their state-building should not be underestimated. Of necessity, the mid-century reforms had devolved considerable power on the provinces and provincial gentry. The recovery programme in the countryside helped to revive the unwritten compact between the peasant and his scholar-gentry rulers. But the gentry were also bound more tightly to the empire by the progressive displacement of the high Manchu officials by ethnic Chinese: with a more unified elite, China was gradually becoming more completely a Chinese state â although recent research suggests that Manchu predominance remained a bone of contention.

84

China might not have been able to match the industrial output or modern firepower of the European states, but her cultural and social solidarity had been strengthened just in time for the crisis years after 1890.

Nor in the meantime had the European states been able to turn the Middle Kingdom into a mere semi-colonial periphery. The treaty ports had been meant as bridgeheads into the Chinese economy, opening it up Indian-style to Western manufactures. But, though foreign trade expanded (to the considerable benefit of the rural economy), Chinese merchants resisted the entry of foreign business into the domestic economy. Foreigners were forced to deal with their Chinese customers through a middleman, the comprador.

85

In a fiercely competitive and uncertain market, there were few easy pickings. The turnover was rapid. By the 1870s, all but two of the largest foreign merchants, Jardine Matheson and Butterfield Swire, had gone to the wall, or made way for new entrants.

86

Compared with India, China (with twice the population) was a far smaller and more difficult market, consuming only half the level of India's imports. When a crash came in the early 1880s, the commercial eldorado the Europeans had imagined seemed to have vanished almost completely.

87

But the real test of China's political and economic independence was yet to come.

In the 1850s and '60s there was every reason to think that Japan would suffer the fate of China, in an even more drastic form. Since the early 1800s the gradual opening of the North Pacific had brought

more and more shipping to the seas round Japan, from Russia (whose âWild East' lay only a few hundred miles to the north), Britain and the United States. In 1853 the Japanese shogun had nervously welcomed the American Commodore Perry, accepting that the era of

sakok u

(seclusion) was over. Five years later, in the âunequal treaties' of 1858, the main Western powers were granted similar privileges of access to those they had extorted from China in 1842. Foreigners would be free to come and trade in a number of âtreaty ports' (the most important was Yokohama, near Tokyo), where they would remain under the protection of their consuls and be exempt from Japanese jurisdiction. Here land would be set aside for their offices, warehouses and residences. Japan would not be allowed to levy customs duties except at a modest rate, to encourage âfree trade' and the diffusion of Western manufactures. With its old isolation once broken, Japan seemed far more vulnerable to Western domination than its vast continental neighbour on the Asian mainland. Its population (

c

. 32 million) was much smaller, though far from negligible in European terms. Its main cities were desperately exposed to Western sea power (Japan had no navy). Russians had invaded Sakhalin (their first landing was in 1806) and threatened sparsely populated Hokkaido, the second-largest island in the Japanese archipelago. And in the early 1860s Japan's political system was on the verge of collapse as a civil war broke out between the Tokugawa shogun and his most powerful vassals in the south and west.

The arrival in force of the Euro-American powers (as a sideshow of their joint coercion of China after 1856) had coincided with and massively aggravated a crisis in the Tokugawa system that had governed Japan since the early seventeenth century. Formally the shogun, who was always chosen from the large and powerful Tokugawa clans, was the viceroy of the emperor, who lived in dignified impotence in his Kyoto palace, several days' journey from the seat of government in Edo. In practice the shogun's power was based on the submission of the numerous and semi-autonomous âdomains' (

han

) and their clan rulers to his authority in a form of vassalage. The

han

were required to pay a tax tribute to the shogun's

bakufu

(literally âtent government'), and their ruling elites were forced to live in alternate years in their great clan compounds in Edo, as so many hostages for good

behaviour. Ultimately the shogun's control rested upon the loyalty of the Tokugawa clans and the support of his other hereditary vassals against the

tozama

or âoutside' clans.

88

But the bakuha

n

system also drew strength from the Confucian ethos that pervaded the samurai caste and emphasized loyalty to the emperor, as well as from the extensive commercial integration that bound the domains into a single market centred on Osaka and Edo.

In the 1820s and' 30s this

ancien reégime

entered a phase of exceptional strain. The underlying cause may have been that agricultural production was now pressed up against its environmental limits. The clearing of forests and more intensive cultivation no longer yielded significant gains: marginal farmlands were dangerously vulnerable to climatic chance.

89

The âTenpo' famines in the 1830s, severest in the north-east, affected the whole of Japan. Domain rulers were squeezed between their obligations to Edo and their local burdens, especially the ârice stipends' to the samurai elite, now largely civilianized as a bureaucratic class. In several large domains, the ruling group took vigorous measures to restore its solvency, repudiating debts, attacking monopolies, encouraging new crops and manufactures, and hoarding bullion.

90

These groups also showed increasing interest in foreign trade, especially in Satsuma (whose long island tail in the Ryukyus stretching far away towards Taiwan had long been the avenue for trade with China), and in the more systematic acquisition of âDutch' knowledge â information about the West and its civilization that leaked through the keyhole port of Deshima, the Dutch trading station in Nagasaki harbour. At the same time, the leading domains in the south and west, Choshu and Satsuma, were acutely aware of the growing threat of Western intervention, to which they were most exposed. By the 1850s, both were buying modern firearms, cannon and steamships, and experimenting desultorily with Western metallurgy to make their own weapons.