Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe (12 page)

Read Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe Online

Authors: Ian Castle

Tags: #History, #Europe, #France, #Military, #World, #Reference, #Atlases & Maps, #Historical, #Travel, #Czech Republic, #General, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #19th Century, #Atlases, #HISTORY / Modern / 19th Century

With his army on the move, Napoleon left Strasbourg to conclude the diplomatic missions his aides had begun in Baden and Württemberg. By the time he departed he had secured about 7,000 Württemberg and 3,000 Baden troops for service on his lines of communication. Quite how the three fiery Francophobe daughters of the margrave of Baden – the tsarina of Russia, the queen of Sweden and the electress of Bavaria – reacted to their father’s decision is not recorded.

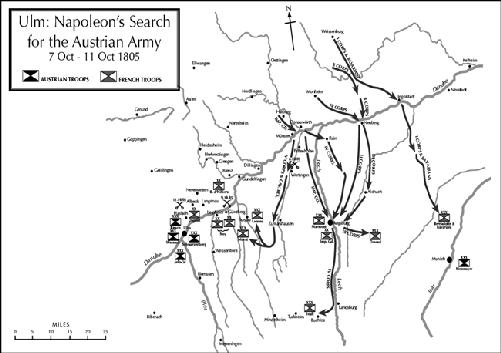

In the absence of any clear information on Austrian movements, Napoleon relinquished command of the left wing of the army – I and II Corps as well as the Bavarians – to Bernadotte, while he retained control of the rest of his forces. On 3 October the front of the army contracted to around 125 miles, its progress closest to the line of the Danube shielded by wide-ranging cavalry screens: but prisoners still eluded them. However, Napoleon still had a network of spies operating in Bavaria and a report of 2 October told of the construction of entrenchments around Ulm, along the Iller and in front of the passes exiting from Tirol. Then, a report on 4 October suggested that the Austrians were withdrawing from their positions west of the Iller and pulling back towards Ulm.

The report was correct. Mack also had spies and scouts out in all directions and finally information from Kienmayer’s patrols, probing north-west from Donauwörth, reported the approach of large bodies of the enemy. There could now be no doubt that the French move from the Black Forest was a feint and Kienmayer had located the main body approaching from Stuttgart and beyond. Yet Kienmayer was still unaware that French troops under Bernadotte had, on 3 October, entered Ansbach, the Prussian territory that Francis had assured Mack was inviolable. Seemingly unperturbed by the news of the French approach, Mack issued orders for the army to swing into new positions behind the Danube facing north. Schwarzenberg’s corps was to occupy an area just south of Ulm, Riesch’s men headed for positions in and around the city, while Werneck’s command received orders to line the Danube between Leipheim and Günzburg. All units were required to take up these new positions by 8 October. To strengthen the position, Austrian troops removed planking from the bridge at Elchingen on 3 October, then two days later destroyed the bridge at

Thalfingen. This meant the first intact bridges east of Ulm stood at Leipheim and Günzburg, at least 23 miles away.

As it now appeared likely that the Austrian army was redeploying on the Danube, and he knew of Austrian activity north of the river (Kienmayer’s troops), Napoleon demanded that Murat bring in some of these men: ‘What I want is information – send out agents, spies, and above all make some prisoners.’

1

But again the Austrians avoided capture.

By 5 October the entire Grande Armée occupied a front narrowed to 65 miles, the only obstruction between them and the Danube formed by the 16,000 men of Kienmayer’s corps strung out over 35 miles between Nördlingen and Eichstadt. In fact it was on the extreme far right of this thin Austrian line, where little likelihood of danger was expected, that a weak detachment of three battalions of infantry and a regiment of hussars under Generalmajor Nostitz discovered Bernadotte’s army of 37,000 men rapidly approaching from Prussian territory. Clearly Kienmayer could not contain this overwhelming force massing against him and on 6 October he withdrew rapidly across the Danube at Neuburg, sending detachments to protect the bridges at Donauwörth, Rain and Ingolstadt. Later that day, Vandamme’s division of IV Corps arrived at Harburg, only 5 miles from Donauwörth. Alerted to their proximity, the Austrians in the town began breaking up the bridge, but around 8.00pm – before the task was even half completed – French troops arrived in overwhelming numbers and drove the defenders away. By the following morning the bridge over the Danube at Donauwörth was secure and repaired. While Vandamme consolidated this important gain, the entire French army hovered within a day’s march of the Danube.

The march had been a tremendous achievement for the French army, yet it had not been without problems. The opening of the month of October brought a great change in the weather. The warm sunny days of September gave way to rain, cold winds and even a little snow, and Napoleon’s determination that the army should proceed with all speed allowed little time for foraging. One man who experienced the hardships of the march left this revealing description:

‘The extremity of fatigue, the want of food, the terrible weather, the trouble of the marauders – nothing was wanting … The brigades, even the regiments were sometimes dispersed, the order to reunite arrived late, because it had to filter through so many offices. Hence the troops were marching day and night, and I saw for the first time men sleeping as they marched. I could not have believed it possible. Thus we reached our destination without having eaten anything and finding nothing to eat. It was all very well for Berthier to write: ‘In the war of invasion as the emperor makes it, there are no magazines; it is the Generals to provide themselves from the country as they traverse it’; but the Generals had neither the time nor means to

procure regularly what was required for the needs of such a numerous army. This order was an authorisation of pillage, and the districts we passed through suffered cruelly. We were often hungry, and the terrible weather intensified our sufferings. A steady cold rain or rather half-melted snow fell incessantly, and we stumbled along in the cold mud churned by our passage almost up to our knees – the wind made it impossible to light fires.’

2

The appalling conditions made life difficult for the Austrian forces too. Mack’s widely deployed army trudged slowly through the dreadful weather to their newly allocated positions. The poor road conditions also delayed messengers, and it was only on the morning of 7 October that Mack, in Ulm, heard of the loss of the Donauwörth bridge. In response he ordered Riesch, whose command was forming around Ulm, to proceed towards Günzburg, and for Jella i

i to leave a brigade between Lake Constance and the Iller, a detachment in Memmingen, and then march with the rest of his men to Ulm. At 4.00pm Mack arrived at Günzburg, about 30 miles upstream from Donauwörth, to check the position and prepare to threaten any French formations crossing the Danube. Here he heard for the first time that French troops had passed through Ansbach, contrary to everything he had been assured by the kaiser. Surprised by this revelation Mack later wrote: ‘The situation of the army was certainly gravely compromised by the sudden appearance of an enemy more than twice its superior in numbers, but I did not consider it desperate.’

to leave a brigade between Lake Constance and the Iller, a detachment in Memmingen, and then march with the rest of his men to Ulm. At 4.00pm Mack arrived at Günzburg, about 30 miles upstream from Donauwörth, to check the position and prepare to threaten any French formations crossing the Danube. Here he heard for the first time that French troops had passed through Ansbach, contrary to everything he had been assured by the kaiser. Surprised by this revelation Mack later wrote: ‘The situation of the army was certainly gravely compromised by the sudden appearance of an enemy more than twice its superior in numbers, but I did not consider it desperate.’

Mack’s immediate thought was to gather the army together, push through the French units already established south of the Danube, and join forces with Kienmayer for a retirement on the Inn. However, his army was already following redeployment orders and in the atrocious weather it would prove an enormous task to locate all the dispersed units and issue new instructions. Instead, he decided on a concentration on Günzburg and Burgau while awaiting Russian support. He held ample supplies west of the Lech and by maintaining communications with Kienmayer, now at Aichach on the road to Munich, he could offer a double threat to French movements. Additionally, the bridges near Günzburg offered him the opportunity to cross to the north bank of the Danube and present a threat to French communications. Finally, the French violation of Ansbach held the possibility of immediate Prussian armed intervention.

Under the circumstances Mack was not unduly worried. Expressing his confidence on the morning of 8 October, he despatched a letter to Kutuzov, whose arrival on the Inn he anticipated within the next two weeks: ‘We have enough to live upon in the district west of the Lech – more than enough in fact to last us until the Russian army reaches the Inn, and will be ready to move. Then we shall easily find the opportunity to prepare for the enemy the fate he deserves.’

3

Mack now prepared new orders for the army, while the formations closed on their original objectives. One of these, FML Auffenberg’s division, nearing the end of a long march from Tirol, was heading towards the Lech, where he expected to form a junction with Kienmayer’s corps. After an eleven hour overnight march, Auffenberg arrived with his exhausted and hungry division in the town of Wertingen at 7.00am on 8 October. Awaiting him were instructions from Mack cancelling his march on the Lech. These ordered him to fall back 12 miles to Zumarshausen, situated on the road to Augsburg, where he was to form the advance guard of the force Mack intended to collect near Günzburg to oppose the French. The order must have dismayed Auffenberg. He had under his command some 5,000 infantry and 400 cavalry, but his men were exhausted and he felt they must rest before retracing their steps. At about midday reports arrived in Wertingen of French troops approaching on the road from Donauwörth. To investigate, Auffenberg despatched a force of two cavalry squadrons and four companies of infantry towards Pfaffenhofen. Before they could reach this village they encountered the leading elements of Murat’s cavalry and Lannes’ V Corps. It was no contest and the Austrians streamed back towards Wertingen to raise the alarm.

On the previous day, 7 October, the French began crossing the Danube in numbers. While repairs to the bridge at Donauwörth were underway, Murat rode a few miles upstream and discovered the bridge at Münster standing undefended. He crossed and returned towards Donauwörth on the southern bank, driving away any of Kienmayer’s detachments still lurking in the area. Soult’s IV Corps was now crossing at Donauwörth and Lannes’ V Corps marched to Münster.

Napoleon arrived at Donauwörth the same day and convinced himself that the only logical move for Mack was to march from Ulm, through Augsburg to Munich. He dismissed the idea of an Austrian move north of the Danube. Accordingly, he issued orders for IV Corps to advance from Donauwörth and march on Augsburg. Davout, still approaching the Danube, was to cross at Neuburg and continue southwards to Aichach. Marmont, following over the river at Neuburg, marched downstream to Ingolstadt to prepare the bridge there for Bernadotte’s I Corps and the Bavarians. Ney, with VI Corps, initially received orders to remain on the north bank of the Danube, but to send one division over to the opposite bank to form a link with Lannes. Napoleon, convinced no garrison of any strength remained in Ulm, informed Ney: ‘I cannot imagine that the enemy could have another plan, other than to withdraw itself on Augsburg or Landsberg or even Füssen. It is possible, nevertheless, that he hesitates and in this case it is up to us to ensure that none escapes.’

4

The remaining formations of the army – Murat’s Cavalry Reserve and Lannes’ V Corps – were to move southwards to cut the Ulm–Augsburg road at Zumarshausen. Directly in their path lay the startled Auffenberg and his isolated division.

Although surprised, the Austrian general reacted quickly, placing four grenadier battalions on the high ground to the left of the Günzburg road with 21/2 squadrons of

cuirassiers

protecting his flank. The rest of the infantry occupied positions in Wertingen or formed detachments in the surrounding hamlets. The most forward of these detachments, close to 200 infantry at Hohenreichen, threw back the first two attacks by dismounted dragoons, but the third attack, involving eight dismounted squadrons from Général de division Beaumont’s 3ème Dragon Division – perhaps 900 men – succeeded in capturing the ramshackle collection of buildings. Remounting, the dragoons reformed and, joined by the 1er Dragon Division and supported by artillery fire, they cleared the other outlying Austrian detachments and isolated the defenders of Wertingen from their grenadier battalions drawn up in square on the hill.