B0038M1ADS EBOK (20 page)

Authors: Charles W. Hoge M.D.

Humans are reactive beings. We react to all sorts of things occurring around

us, as well as to what's going on internally. Everyone reacts to things differently. Our reactions are influenced by who we are, how we're feeling at the

moment, our physical health, how much stress we're experiencing, what's

happening around us, and how we've been raised and trained. If you're in

pain or haven't been sleeping well, then you're likely to react differently

than if you're well rested and pain-free. A comment someone makes may

send one person into a tirade while someone else would just laugh it off.

Being stuck in traffic can trigger anger, frustration, anxiety, fear, humor,

indifference, and other emotions. Reactions are fluid and depend on a lot

of different factors.

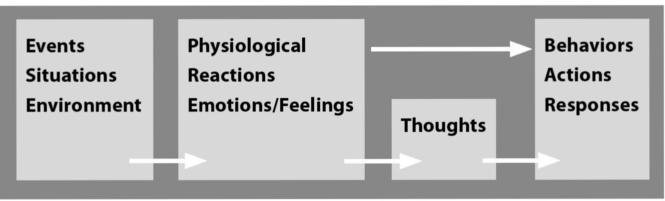

Reactions can automatically lead to behaviors, and one objective of

this chapter is to increase your awareness of these automatic responses.

An event or stressful situation in our life perceived through our senses

(sight, sound, touch, smell, taste) causes physiological and emotional reactions. If I stub my toe on a table, I immediately feel pain in my foot, along

with anger, which I may express verbally ("Ouch!"). If I immediately kick

the table in response, this behavior almost certainly involved no thought.

However, if the pain or anger caused me to feel upset with myself for being

clumsy and I kicked the table out of frustration at my own inadequacy, then

a thought (e.g., "I shouldn't be so clumsy") contributed to my behavior.

Combat experiences tend to shorten the time between stressful events

and behaviors. Warriors often have hair-trigger reactions to stressful situations, and this can lead to behaviors they later regret. A stressful event may

automatically result in an action without paying any attention to the feelings or thoughts inside. In addition to specific stressful events, we're also

constantly reacting physiologically and emotionally to everything going on

in our environment. Feelings are always present, whether or not we know

what specific things are causing them.

The goal of this chapter is to become more aware of the range of physiological reactions and feelings, and how these are connected with behaviors and influenced by war-zone experiences. Specific navigation exercises

are provided to help you learn to modulate your reactions.

SKILL 1: LEARN TO PAY ATTENTION TO YOUR

PHYSIOLOGICAL REACTIONS AND ANXIETY LEVEL

Combat teaches a warrior how to become highly attuned to any physiological warning signs of anxiety or danger. If you feel your heart suddenly

start to race; your breath quicken; the hair on your arms raise up; or your

neck, chest, or upper back tense, these are all probably your warning signs

of danger. You may also start to sweat or feel discomfort in the pit of your

stomach. You may have a sensation that something bad is about to happen,

almost a premonition, and become hyperalert, keyed up, scanning around

for danger, aware of escape routes, and prepared to respond immediately.

These physical manifestations of anxiety go together with anger, which

is understandable, since "fight" is part of the fight-or-flight reflex, and

adrenaline and anger go hand in hand. The "flight" part makes you feel a

strong urge to get out of whatever situation or place you're in.

These reactions are not just about being prepared to fight an enemy

or run away from danger. What they mean for a warrior is being prepared

to respond to danger of any kind-for example, a fire, accident, natural

disaster, or when someone is trying to break into your home. As a warrior, you're much better prepared to respond to danger than most people.

This includes not panicking when something unexpected happens, and responding without hesitation in the most efficient way to protect yourself

and others around you. Oddly, a sense of panic can happen when there

is no danger, but when chaos breaks out, warriors often feel much calmer

than non-warriors.

A warrior's body knows how to respond to threat and danger, and how

to handle high anxiety, stress, and fear. Underlying many of the physiological reactions of anxiety is fear, although a warrior's perception and

response to fear is different than the response of an untrained person.

Warriors understand how to use fear to their advantage, to tune in to their

level of fear as a warning signal, and then to dial up or down their level

of alertness, tension, and awareness of potential threats. For example, in

the combat zone, if a platoon drives through a sector where it was previously ambushed, all members of the team will tense up, even if they

know the area was cleared and is now considered safe. Warriors don't talk

much about being helpless or paralyzed by fear, but instead about how

their training helps them to function effectively in the face of fear. Fear

becomes almost a sixth sense.

The body's reaction to threat includes changes in alertness, mental

attention, muscle tension, heart rate, and general anxiety. Being aware

of these responses allows you to monitor yourself in whatever situation

you may be in.

Anxiety and its associated physiological reactions are the surface manifestations of fear. It's important to be able to monitor your level of anxiety-it's the body's warning signal and protector-but having too much

anxiety can lead to indecision and make it difficult to stay focused. With

poor training, warriors are much more likely to succumb to anxiety (or the

deeper emotion of fear), and this can jeopardize the mission and the lives

of team members. Good training is designed to ensure that the warrior

knows what to do in the face of fear.

The goal of this exercise is to develop greater awareness of your physiological reactions when you sense danger in relation to situations back

home, and learn to monitor yourself better.

In your notebook (or in the space below) note a specific event or situation that happened recently that triggered a strong sense of danger or strong physiological reactions. Then list the physiological sensations you

experienced:

To learn to become more aware of your body's reaction to threat or

danger, photocopy the following scale related to physiological reactions.

Use this scale to keep track of your level of alertness, muscle tension, mental focus, heart rate, and overall anxiety distress. You can use this in three

ways, to note: 1) how much anxiety you're carrying right now; 2) the highest level of anxiety that occurred over a period of time (such as over the

course of a day); and 3) the highest level of anxiety that occurred related

to a specific stressful situation, and how long this lasted.

Use this scale to monitor yourself over time, and when you do other

exercises in this book. For example, once a day write in your notebook

the highest level of physiological reactions that you experienced and how

often it occurred. You can do this for any other time period as well, such

as once a week.

Physiological Reactions Scale (circle)

Consider a "3" or "4" on each line of the physiological reactions scale

to be generally a normal state of being awake, alert, and able to concentrate and focus with minimal distress or anxiety. At the lowest end of the

scale, you feel sleepy, relaxed, or dull. At the highest end of the scale, your

body is hyperalert, your muscles are tense, your mind may be jumpy or

unable to focus on one thing, and you feel high anxiety or distress. Normally you should not be aware of your heartbeat, but when you're revved

up, you're more likely to feel your heart racing or pounding. When you

sense danger, or feel physiological reactions to a stressful situation, it's

likely that you'll experience levels ranging from "5" to "10."

When there is danger, different things can happen to your focus and

ability to pay attention. First, you may scan the environment around you

for threats. The mind jumps rapidly from one thing to another, never setding on anything for long. You feel distracted and restless, and your mind

doesn't stay still; a term that has been applied to this is "monkey mind."

The second thing that can happen is your attention becomes like tunnel

vision, focused only on one point or location where you think the greatest

threat is. Both types of attention can be protective, and both can also be

detrimental to your safety, depending on the situation. If your mind is so

jumpy that you're unable to focus when you need to, or your head is swiveling from side to side or your eyes are darting rapidly, that can be bad; alternatively, if your focus is too much like tunnel vision, you may miss a threat

from somewhere else. Warriors often shift back and forth between the

more diffuse and focused attention, according to their training and the

situation. For example, as warriors approach a building where there may

be a target, their attention is focused not just on the building but also on

scanning all sides, since they cannot be sure where the greatest threat is.

When they enter the building, each member of the team becomes highly

focused on the specific direction that they're supposed to cover.

There is another type of focus, which is neither jumpy nor tunnel-like.

It's a wide relaxed focus, where your attention is largely oriented toward one

direction-say, the building you are about to enter-but you're also tuned

in to your peripheral vision and are aware of what is going on around you

without looking quickly from side to side. This allows you to respond quickly to a threat in front of you and to threats from either side. The mind is also

quieter and less jumpy. The wide relaxed focus is a skill that can be practiced, and will be covered later, in the section on meditation.