Battleship Bismarck (23 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

Kapitänleutnant (Ingenieurwesen) Gerhard Junack, the turbine engineer during Exercise Rhine, whose action station was in the middle turbine room. On the evening of 26 May he took part in the attempt to repair the

Bismarck’s

rudder. He is among the handful of survivors. After the war he served in the Federal German Navy, attaining the rank of Kapitän zur See. This photograph was taken at Prisoner-of-War Camp 30 at Bowmanville, Ontario, Canada. (Photograph courtesy of Josef Statz.)

The Fleet Commander, Admiral Günther Lütjens, a man not given to confiding his reasoning or intentions. (Photograph from Bundesarchiv, Koblenz.)

Lütjens’s taciturnity probably ensured that deliberations at his level were restricted to a very small circle, anyway. Finally, the fact that we were at general quarters almost continually from the time we entered the Denmark Strait on 23 May until the end on 27 May made conversation among the officers next to impossible.

The tactical conduct of the operation must, therefore, be based primarily on the

Bismarck’s

War Diary as it was reconstructed from

whatever material was available at installations ashore.

*

Obviously a document so produced cannot be entirely satisfactory because, for example, it cannot show whether the embarked B-Dienst team or shipboard radio and listening equipment provided Lütjens information that Group North and Group West did not have and, if so, what that information was. Nor can the reconstructed diary show why and how new decisions brought about by significant developments in the course of the operation were reached.

*

Midshipman (B) designated officers with a career specialty in naval construction (Baulaufbahn).

†

Electrical team.

*

On the orders of the commander in chief of the Kriegsmarine, Grossadmiral Raeder, at the beginning of July 1941 the

Prinz Eugen’s

chief wireless officer, Kapitänleutnant Hans-Henning von Schultz, was detailed to Naval Group Command West (Paris) for three weeks to reconstruct the

Bismarck’s

War Diary in respect to technical signals matters. He had the help of the originals of all radio messages received by the

Prinz Eugen

during the Exercise Rhine, the visual signals traffic between the

Bismarck

and the

Prinz Eugen

, and the B-Dienst reports received.

|

Early on the morning of 23 May, in foggy, rainy weather, the

Bismarck

and

Prinz Eugen

entered the Denmark Strait. Around 0800 the wind, which had been blowing from the south-southwest, veered to the north-northeast, and thus again came from astern on our new, westerly course. Around noon a new weather forecast from home promised that weather favorable for our undetected passage of the strait would continue on the twenty-fourth: “Weather 24. Area north of Iceland, southeasterly to easterly wind, Force 6–8, mostly overcast, rain, moderate to poor visibility.” In spite of this welcome message, in the afternoon visibility increased to fifty kilometers, but before long intermittent heavy snow caused it to vary considerably between one point on the horizon and another: to port, in the direction of Iceland, heavy haze hung over the ice-free water; on our bow, in the direction of Greenland, there were shimmering, bluish-white fields of pack ice and the atmosphere was clear. The high glaciers of Greenland stood out clearly in the background, and I had to resist the temptation to let myself be bewitched by this icy landscape longer than was compatible with the watchfulness required of us all as we steamed at high speed through the narrowest part of the strait, with our radar ceaselessly searching the horizon. We would not have welcomed this clear visibility even if we had not been expecting intensified British reconnaissance. I could not help thinking of the warnings Externbrink had given Lütjens.

Suddenly, at 1811, alarm bells sounded throughout the

Bismarck:

vessels to starboard! The task force turned to port but the “vessels” revealed themselves to be icebergs. Ice spurs and ice floes piled one on top of another frequently led young men, unaccustomed to recognizing objects at sea, to report nonexistent ships and submarines. Excusable, but dangerous, because when a man had made several incorrect observations he might be afraid to report any sighting. But that wasn’t all. Sometimes the air over the glaciers of Greenland caused mirages that fooled even the old sea dogs. When that happened, the officers on the bridge were liable to see ships and shapes that were not there.

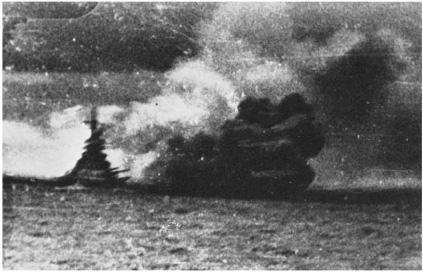

From 1800 to 2400, German Summer Time, on 23 May, Breakout through the Denmark Strait. (Diagram courtesy of Jürgen Rohwer.)

Shortly before 1900 we entered the pack ice. From then on, we had to steer a zigzag course through heavy ice floes that pressed hard against the ship’s side and could have damaged our hull. In an area three nautical miles wide, visibility ahead and to the edge of the ice to starboard was now completely clear. To port, there was haze in the distance and, in front of the haze, there were patches of fog.

It was 1922 when the

Bismarck’s

alarm bells sounded again. This time our hydrophones and radar had picked up a contact on our port bow. I stared through my director but could not see anything. Perhaps the contact was hidden from me by the ship’s superstructure. Our guns were ready to fire, awaiting only the gunfire-control information. It never came. Whether the “contact” was a shadow on the edge of a fog bank or a ship bow-on or stem-on, perhaps very well camouflaged, we saw it too fleetingly to fire on it. Our radar registered a ship heading south-southwest at very high speed and plunging into the fog. As the contact moved out of sight, the shadowy outline of a massive superstructure and three stacks was discernible for a few seconds. That was the silhouette of a heavy cruiser—as we learned later, the

Suffolk.

Thereafter the hydrophone and radar bearing of the vanished enemy soon shifted astern and the range increased. With exemplary speed, the B-Dienst team in the

Prinz Eugen

deciphered the radio signal by which the

Suffolk

had reported us in the course of her turn: “One battleship, one cruiser in sight at 20°. Range seven nautical miles, course 240°.” Lütjens reported to Group North the sighting of a heavy cruiser. When shortly afterwards we saw the

Suffolk

clearly and for some time, she was at the limit of visibility. Her small silhouette revealed that she was trailing us astern.

*

The County-class heavy cruiser

Suffolk

, the ship that shadowed the

Bismarck

by maintaining radar contact from the evening of 23 May until the early morning of 25 May. She is down here wearing camouflage and patrolling the North Atlantic in the spring of 1941. (Photograph from the Imperial War Museum, London.)

There was another alarm in the

Bismarck

at 2030 and “full speed ahead” was ordered. Our forward radar had made a new contact. Over the loudspeakers, Lindemann informed the crew, “Enemy in sight to port, our ship accepts battle.” Looking through my director in the indicated direction, at first I could see nothing at all. Then the outline of a three-stack heavy cruiser emerged briefly from the fog. It was the

Norfolk

—summoned by the

Suffolk

, to which we had come alarmingly close. The

Norfolk

had suddenly discovered her alarming proximity to our big guns. Flashes came from our guns, which were now trained on her, and in a moment we could see the splashes of our shells rise around the cruiser, which laid down smoke and turned away at full speed to disappear into the fog. According to the

Norfolk’s

after-action report, three of our five salvos, all that we could fire in so short a time, straddled their target. A few shell fragments landed on board but no hits were scored. The

Norfolk

stayed hidden in the fog for a while, then reappeared astern to join the

Suffolk

in shadowing us. The word was passed to our crew. “Enemy cruisers are sticking to our course in order to maintain contact.”