Battleship Bismarck (19 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

The crew was in the state of tense anticipation that comes when a long period of preparation is finally over and the action for which it was designed is about to begin. Their faith in their captain and their ship was boundless, even though they knew nothing about the operation on which they were embarking. Now, they heard Lindemann announcing over the loudspeakers that we were going to conduct warfare against British trade in the North Atlantic for a period of several months. Our objective was to destroy as much enemy tonnage as possible. This message confirmed what the men had long suspected. Their apprehension about the unknown was replaced by certainty. Below, the gentle vibration of the engines reminded them of the tremendous power that made their ship a deadly weapon.

Our passage to the west, under a cloudy sky, with medium wind and seas, was uneventful. Escorted by the destroyers

Z-23

and

Friedrich Eckoldt

and preceded by Sperrbrecher, the task force sailed as a unit after leaving Rügen and reached designated positions on schedule. Around 2230, the

Hans Lody

, carrying the commander of the 6th Destroyer Flotilla, Fregattenkapitän Alfred Schulze-Hinrichs, joined the formation and we steamed north through the Great Belt. To maintain the secrecy of our mission, the commander of the Baltic security forces announced that the Great Belt and the Kattegat would be closed to commercial traffic on the night of 19–20 May and the following morning.

Next day, when we were in the Kattegat, the

Hans Lody

sounded our first aircraft alarm. We in the

Bismarck

assumed that we had been sighted by British reconnaissance planes. However, they turned out to be our own fighters, of whose arrival we had not been informed.

In contrast to the preceding day, 20 May was clear and sunny. It was perfectly beautiful. The shimmering green sea, corded with the light blue of many small swells, stretched to the far horizon. As we passed the small, flat island of Anholt to port, the tall, slender lighthouse on its northeastern end was clearly visible. This radiant weather might have been seen as a good omen for our operation. If only we hadn’t had to steam in such clear view of the Swedish coast and among innumerable Danish and Swedish fishing boats. They seemed to be everywhere, these little white craft with their chugging motors, some of them bobbing up and down beside us. Not only that but steamers from all sorts of countries were passing through the Kattegat. If this wasn’t a giveaway of what we were doing here, what was? Surely the appearance of our task force in Scandinavian waters would attract attention that might well work to our disadvantage. Would Sweden’s neutrality, which at that time was benevolent towards Germany, avert the military damage that the vigilant Norwegian underground was certainly eager to inflict on us? It was not exactly a secret that the Norwegian underground was in touch with London. But more than that. As our Seekriegsleitung was well aware, Stockholm and Helsinki were hotbeds of British intelligence, and British naval attaches there reported all known German ship movements and other German military operations to London. Indeed, we knew that on 15 March 1941, the British naval attaché in Stockholm informed the Admiralty that an organization had been set up to observe ships passing through the Great Belt and that its reports could reach him in twelve hours. Captain Troubridge, too, had thought about navigation in these waters when he made a duty visit to the area in July 1939. “I should think,” he confided to his diary, “it would not be difficult to slip through unseen on a dark night provided the ship was darkened. It would be the obvious place for a S/M [submarine] patrol in time of war.”

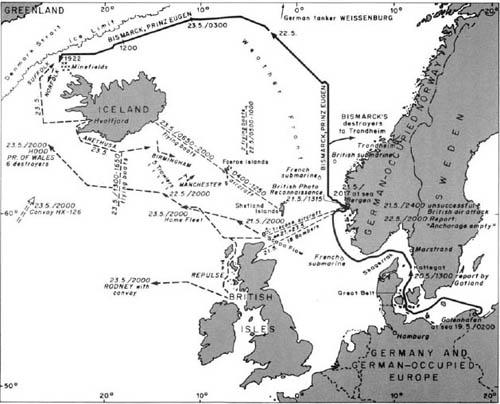

From 1700, German Summer Time, on 18 May to 2000, German Summer Time, on 23 May. The beginning of Exercise Rhine. (Diagram courtesy of Jürgen Rohwer.)

It ran through my head that enemy agents were being handed a unique opportunity to identify and report our task force just as it was putting to sea. On top of that, the weather was perfect for aerial reconnaissance. I could not see how Exercise Rhine could possibly be kept secret. I became still more concerned when around 1300 the Swedish aircraft-carrying cruiser

Gotland

came in view to starboard against the Swedish coast. The

Gotland

, in accordance with a longstanding training program, was just then on her way to gunnery practice off Vinga, that is, in Swedish territorial waters directly west of Göteborg, and even steamed on a parallel course to us for a while. Assuming that the

Gotland

would inform the Swedish Admiralty that

we had been sighted, Lütjens radioed Group North, “At 1300 aircraft-carrying cruiser

Gotland

passed in clear view, therefore anticipate formation will be reported.” The commander in chief of Group North, Generaladmiral Rolf Carls, replied: “Because of the strictly neutral conduct of Sweden, I do not think the danger of being compromised by the Swedish warship is any greater than from the already present, systematic enemy surveillance of the entrance to the Baltic.”

But if Lütjens did fear that we had been dangerously compromised, it was he, not Carls, who was right. Captain Agren, of the

Gotland

, immediately sent a secret radio signal reporting our passage through the senior naval officer at Göteborg to the commander of the west coast naval district at Nya Varvet, who in turn notified naval headquarters in Stockholm.

*

*

There being nothing in writing on this matter, I asked Vizeadmiral Helmuth Brinkmann if this was the case but he could not recall that Lütjens gave his reasoning.

*

It was not this report, however, that gave naval headquarters in Stockholm the first news of the German operation. Knowledge of it had already been gained by an aerial reconnaissance, during which five picket vessels had been sighted about 1200 around twenty nautical miles west of Vinga, followed about ten nautical miles astern by a task force described as three

Leberecht Maass-class

destroyers plus a cruiser and a very large warship [

Bismarck?

]—ten or twelve aircraft had overflown this task force, which was holding a northerly course. For her part, the

Gotland

reported having sighted two German battleships and three Maass-class destroyers to Nya Varvet about 1300. Thereafter she had raised steam in all boilers and followed the German task force on a northerly course along the edge of Swedish territorial waters. Around 1545 the

Gotland

reported that the German ships had gone out of sight on a northwesterly course.

|

Early in 1941, a few high-ranking officers in the Swedish intelligence service privately came to the conclusion that a weakening of Germany would be greatly to the advantage of their country. They considered the German invasion of Denmark and Norway an outrageous attack on the sovereignty of all Scandinavia, and, after February 1941, worked closely with the Norwegian underground. Some of their contacts with this movement were through the Norwegian government-in-exile’s military attaché in Stockholm, Colonel Roscher Lund, who had become a friend and trusted informant of the British naval attaché there, Captain Henry W. Denham.

On the evening of 20 May, Roscher Lund learned from Lieutenant Commander Egon Ternberg,

*

who belonged to the Swedish secret intelligence service, the so-called Bureau C of the armed forces’ high command in Stockholm, that, during the day, two large German warships and several merchantmen had passed through the Kattegat on a northerly course under air cover. He hastened to the British embassy, where he was told that Denham was at a certain restaurant in the city. He pursued him there and gave him the important news. Both returned immediately to the embassy and, with reference to an earlier observation that day, cabled the Admiralty in London: “Kattegat

today 20th May. (a) This afternoon eleven German merchant ships passed Lenker North; (b) at 1500 two large warships, escorted by three destroyers, five escort vessels, ten or twelve aircraft, passed Marstrand course north-west 2058/20.” On 23 May, Denham wrote Roscher Lund a letter of thanks:

Your very valuable report of enemy warships in the Kattegat two days ago, has enabled us to locate in the fjords near Bergen on 21st

one Bismark [sic] battleship

one Eugen cruiser.

Naturally there is no harm in your making use of this to enlighten your source.

Thank you so much for your very helpful efforts—let us hope your friend will continue to be such a valuable asset.

Ternberg had seen the

Gotland’s

sighting report in the Admiralty in Stockholm and immediately advised Roscher Lund of its contents, but for security reasons he did not reveal the source of his information. And it was routine for the

Gotland

to report the presence of foreign warships in or near Swedish territorial waters.

Of course, at the time, I did not know of these events, but even so, it did seem to me on 20 May that there had been far too many opportunities for our formation to be sighted and, when I thought about what this might do to our mission, I felt that a shadow had fallen over it.

*

I doubt that I was the only one in the ship who had such thoughts, yet none of my younger shipmates, at any rate, said anything about it. What good would it have done? Nothing could be changed. The only thing to do was hope for the best. No one in the

Bismarck

had any inkling of the rapidity with which the news would reach the British Admiralty or of the energetic and successively wider-reaching steps the sea lords would take.

*

Roscher Lund never divulged the name of this officer. He spoke of him as his “source.” Lieutenant Egon Ternberg had retired not long before but was recalled because of the war and assigned to Bureau C. In 1941 he was promoted to commander. He is likely to have had excellent contacts with Roscher Lund.

*

That indications of the

Bismarck’s

departure on an operation reached the British and Swedish by other means besides aerial reconnaissance and the sighting by the

Gotland

was worked out at an international conference of the Study Group for Military Research (Arbeitskreise für Wehrforschung) in Stuttgart in 1978. The relevant finding reads: “The Swedish intelligence service, which was also very active in code-breaking, had tapped the German telegraph lines to Norway, which had to run partly through Swedish territory, and obtained important information from them. Swedish intelligence officers who sympathized with the Allies gave this information to the military attaché of the Norwegian government in exile, who in turn relayed it to the British attachés in Stockholm, and the latter transmitted it—though never verbatim—to London. In this way, for example, the first information regarding the sailing of the battleship

Bismarck

came into British hands.” (Communication from Hans-Hennig von Schultz to the author.)

|