Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (48 page)

Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

Were Crummell’s worries justified? From one perspective, the black elite

could

in fact be charged with frivolous aping. They appeared to be unthinkingly replicating some of the silly pretensions of New York’s “Knickerbocracy” and its chief spokesperson, Ward McAllister, who in the early 1870s created the “Patriarchs,” a select club of the city’s best twenty-five men, and later established a list of New York’s “Four Hundred.”

13

Several impulses might have been at work. For one, society life is fun and pleasurable. Who doesn’t love to dress up, eat fine food, and dance the night away? For another, it’s possible that members of the black elite were convinced that their new lifestyle would serve as an effective counterargument to the scientific racists, serving as proof positive that they were just like white elites, monied, fashionable, socially adept, American citizens just like them. This strategy was fraught with peril, however. It risked mockery from whites of all classes, who could not take seriously the idea that blacks of any class could be their social and intellectual equals. More dangerously, it risked separation from the less fortunate of their race, from those who thought of the elite as whitewashed blacks.

Class distinctions had existed in the black community before the Civil War, but as demographic shifts swept the country at century’s end, they became even more sharply defined. Black migrants from the South flooded into the North: 70,000 arrived in the 1870s, followed by 88,000 in the 1880s, and 140,000 in the 1890s. Most of those who came to the New York area settled in Manhattan. Many fewer chose Brooklyn, where the black population only rose from 5,000 in 1870 to 10,300 in 1890, while the total population increased from 396,000 to 1,170,000. Furthermore, the number of blacks in Brooklyn was dwarfed by the influx of Irish- and German-born inhabitants, which stood at approximately 90,000 each, as well as by the rapidly increasing Italian and Russian populations. Stuck at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder, most blacks still maintained unskilled jobs, the men working as laborers, porters, whitewashers, and seamen, the women as domestics and laundresses. Only a few occupied skilled trades as barbers, tailors, carpenters, or dressmakers. In her memoir, Maritcha noted how much these postwar decades constrained black lives. With considerable bitterness, she

complained that competition with European immigrants, advances in technology, and the rise of labor unions had combined to create a “triangular” relationship of “cupidity, caste and callousness” that effectively “disbarred” blacks from economic life.

14

Concerned for its own social and economic stability, the elite was anxious about, if not threatened by, the influx of blacks into the area. As in the years before the Civil War, those who were well off feared that whites would lump upper- and lower-class blacks together and treat them all with the same degree of contempt. Some chose to wall themselves off, retreating into the privacy of their homes and clubs and attempting to reassure whites that they were no different from them. They distanced themselves from the newcomers by resorting to language analogous to that used by whites:

scum, criminals, loafers, riff-raff, lazy, shiftless, overdemonstrative, undesirable.

Himself a southern migrant, Fortune wrote an editorial trying to dissuade those who hoped to come north. “New York is a good place to shun unless you have plenty of money or a position secured before coming,” he warned, adding that it was not “simply a paradise where employment of all kinds can be had for the asking.”

15

Attitudes were more complicated, however. One Philadelphia observer insisted that it was just as natural for blacks to associate with their own class as it was for whites. “It is the prerogative of every man to select his own company,” he wrote to the Philadelphia-based

Christian Recorder

, “but it is not considered the proper thing for those filling the highest positions in our society to be accepting the hospitality of bootblacks.” Making a racial uplift argument similar to Crummell’s, he went on to argue that the standards of social behavior set by the elite would “benefit the masses and inspire young men and women to seek the best associates.” A New Yorker claimed the exact opposite. “Our aristocracy,” he declared, “is at present more hurtful than helpful, because it stands with frowning face and open sneers at the threshold and sends shivers down the spine of the working middle class.”

16

And reality was more complicated. The plain fact was that class in the black community was fluid, and a fair measure of social mobility did exist. Consider the following biographies of some of the younger members of Brooklyn’s elite.

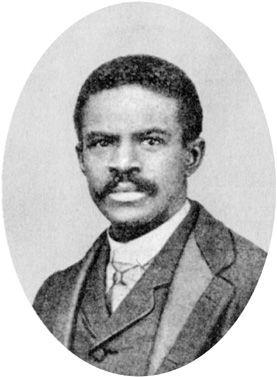

Portrait of T. McCants Stewart, from

Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive, and Rising

, by William J. Simmons (Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library)

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, T. McCants Stewart came from a relatively privileged background. As a child, he received the benefits of private schooling, then attended Avery Normal Institute. Determined to study law, he enrolled at Howard University in Washington, D.C.; he met Charles Sumner and helped lobby for the passage of his civil rights bill. Stewart then returned to his home state to finish his law studies at the University of South Carolina at Columbia, which had opened its doors to all students regardless of race in 1868; he received his bachelor of law degree in 1875. Contemplating a career in the ministry, he entered Princeton Theological Seminary, but left before obtaining a degree. By 1880, he was in New York City.

17

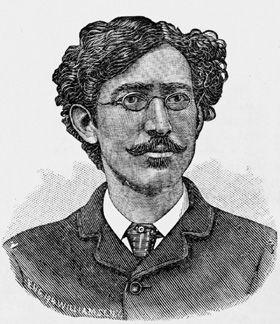

T. T. Fortune, artist unknown (Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library)

T. Thomas Fortune was born, not into privilege, but into slavery in rural Florida. After emancipation, his father moved the family to Jacksonville and served as a state senator during Reconstruction. The young Fortune availed himself of the limited schooling offered by the Freedmen’s Bureau, but also gained a more practical education by observing his father’s political career and working as an assistant printer for local newspapers. Like Stewart, he headed north to attend Howard University, while also working for the

People’s Advocate

where he was introduced to men like Crummell and Frederick Douglass. Fortune left Howard after a couple of semesters and arrived in New York around the same time as Stewart.

18

Unlike Stewart and Fortune, Samuel Scottron’s father was not oriented toward higher education. He moved his family from Philadelphia to New York when Samuel was still a child. According to Booker T. Washington, Scottron senior insisted that his son work with him on a

Hudson River steamer before the Civil War and as a sutler during the war. After the war, Scottron settled in Brooklyn with his mother and sister. Free to pursue his own interests, he attended Cooper Union and received a degree in algebra in 1875. His mother advertised for boarders in the pages of the

Weekly Anglo-African

while his sister promoted herself as a dressmaker. Scottron went on to become an inventor, devising gadgets of all kinds, most notably the adjustable mirror. Much like his father, he was always on the move, traveling far and wide to sell his products.

19

My grandfather, Jerome B. Peterson, was a native New Yorker. All I know about his parents is that his father hailed from Maine and worked as a barber on a ship, while his mother was the daughter of a South Carolina slaveholder and one of his slaves. Educated through high school in New York’s public schools, my grandfather then took a job as errand boy at the Freedman’s Bank. After the failure of the bank, he worked as a clerk in a brokerage business and law office before joining Fortune at the

Freeman

and

Age.

So I would emend Fortune’s dictum to read as follows: New York could be a paradise (relatively speaking) where employment of all kinds, plenty of money, and a secure position could be had for the

working.

Those who undertook this task, however, would need the “hardy muscle” and “strong fibre” that Crummell feared were weakening.

In its March 27, 1888, issue, the

Freeman

saw fit to reprint a speech that an obviously disgusted black businessman had recently delivered to an audience of his peers.

Knowing as we do that the avenues of trade and commerce are almost closed against us, this should tend to make us more economical and educate ourselves as much as possible in any commercial line we are employed, so as to be able to strike out for ourselves at some future date. But do we do it? I know young men who have gotten good situations, getting

good salaries, yet they are entirely ignorant of the business they are in outside of their own immediate duties. They look well, dress well, and have a good time socially.

While I believe that society to a certain extent is good, yet, when we, who can so ill afford it, make social pleasure the main object of our life, instead of trying to accumulate some money with which to embark into some business, I feel that we are doing that which is detrimental both to ourselves and our posterity.

20

The speaker was clearly worried that the younger generation had lost the energy and will to work for the economic betterment of the race and had instead become distracted by the pursuit of aesthetical culture. Had he wanted to offer models of emulation, he could have pointed to four men in my family—the three Peters (Ray Sr. and Jr. and Guignon), and Philip White—who were still actively engaged in their line of business. To buttress his case, he could have quoted from an earlier article in the

Freeman

that had singled out Philip White and Peter Guignon, among others, for praise: “We have traversed Broadway from Central Park to Bowling Green, and all their confluent streets, and we have not discovered one colored man engaged in any business requiring $5,000 capital—except indeed, the wholesale and retail drug business of Dr. Philip A. White, whose eminent success is particularly gratifying. … In Brooklyn we have three colored druggists—Mr. Kissam and Mr. Douglass, and Peter Guignon.”

21

To the names of Peter Guignon and Philip White could be added those of Peter Ray, father and son.

Peter Ray had crossed the East River in 1867 and settled in Williams-burgh on South Second Street, not far from his son and son-in-law’s drugstore. Even though he was in his seventies, Ray was doing extremely well thanks to the continued patronage of the Lorillards. “Four generations of the Lorillards have known his active services,” Ray’s obituary

writer observed, “from the grandfather of the present head to his two sons, who often found it useful to consult a man of his long experience.” When the Lorillards decided to expand their business after the Civil War, they built a factory in Jersey City and rewarded Ray with the position of superintendent, which he held until three weeks before his death in January 1882.

22

This was quite an accomplishment for a black man who had started with the company as an eleven-year-old errand boy. The Jersey City factory was a vast enterprise occupying an imposing red-brick structure that covered a full city block. Its army of workers was divided into different departments headed, according to one commentator, by a superintendent “whose experience has won him the position”; Ray was one of them. In turn, the departments were overseen by a supervisor “who requires a strict accounting from his various subordinates, and the great works are operated like a clock.” They needed to. Tobacco manufacturing was increasingly mechanized. To make plug tobacco, a plug-making machine cut the dried tobacco into the exact size required; hydraulic presses then smoothed the plugs into the finished product. For making chewing or smoking tobacco, the prepared leaf was placed in a trough on a long conveyer belt where it was cut by a knife at 1,200 revolutions per minute. Mechanization increased productivity. In 1883, the Jersey City factory employed 3,500 workers (men, women, and children), dispensed $35,000 a week in wages, manufactured over 25 million pounds of tobacco a year, collected approximately $10 million in annual sales, and paid $32.5 million in federal taxes over a sixteen-year period.

23