Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (39 page)

Read Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin Online

Authors: Timothy Snyder

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #European History, #Europe; Eastern - History - 1918-1945, #Political, #Holocaust; Jewish (1939-1945), #World War; 1939-1945 - Atrocities, #Europe, #Eastern, #Soviet Union - History - 1917-1936, #Germany, #Soviet Union, #Genocide - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Holocaust, #Massacres, #Genocide, #Military, #Europe; Eastern, #World War II, #Hitler; Adolf, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Massacres - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #20th Century, #Germany - History - 1933-1945, #Stalin; Joseph

At the end of the day, the Germans decided to kill Dina Pronicheva. Whether or not she was Jewish was moot; she had seen too much. In the darkness she was led to the edge of the ravine along with a few other people. She was not forced to undress. She survived in the only way possible in that situation: just as the shots began, she threw herself into the gorge, and then feigned death. She bore the weight of the German walking across her body, remaining motionless as the boots tread across her breast and her hand, “like a dead person.” She was able to keep open a small air hole as the dirt fell down around her. She heard a small child calling for its mother, and thought of her own children. She began to talk to herself: “Dina, get up, run away, run to your children.” Perhaps words made the difference, as they had earlier when her mother, now dead somewhere below, had whispered to her. She dug her way out, and crept away quietly.

34

Dina Pronicheva joined the perilous world of the few Jewish survivors in Kiev. The law required that Jews be turned in to the authorities. The Germans offered material incentives: money, and sometimes the keys to the Jew’s apartment. The local population, in Kiev as elsewhere in the Soviet Union, was of course accustomed to denouncing “enemies of the people.” Not so very long before, in 1937 and 1938, the main local enemy, denounced at that time to the NKVD, had been “Polish spies.” Now, as the Gestapo settled in to the former offices of the NKVD, the enemy was the Jew. Those who came to report Jews to the German police passed by a guard wearing a swastika armband—standing before friezes of the hammer and sickle. The office dealing with Jewish affairs was rather small, since the investigation of Jewish “crimes” was simple: a Soviet document with Jewish nationality recorded (or a penis without a foreskin) meant death. Iza Belozovskaia, a Kiev Jew in hiding, had a young son called Igor who was confused by all of this. He asked his mother: “What is a Jew?” In practice the answer was given by German policemen reading Soviet identity documents or by German doctors subjecting boys such as Igor to a “medical examination.”

35

Iza Belozovskaia felt death everywhere. “I felt a strong desire,” she remembered, “to sprinkle my head, my whole self, with ashes, to hear nothing, to be changed into dust.” But she kept going, and she lived. Those who gave up hope sometimes survived thanks to the devotion of their non-Jewish spouses or their families. The midwife Sofia Eizenshtayn, for example, was hidden by her husband in a pit he dug at the back of a courtyard. He led her there dressed as a beggar, and visited her every day as he walked their dog. He talked to her, pretending to talk to the dog. She pleaded with him to poison her. Instead he kept bringing her food and water. Those Jews who were caught by the police were killed. They were placed in cells of the Kiev prison that had held victims of the Great Terror three years before. When the prison was full, the Jews and other prisoners were driven away at dawn in a covered truck. Residents of Kiev learned to fear this truck, as they had feared the NKVD black ravens leaving these same gates. It took the Jews and other prisoners to Babi Yar, where they were forced to disrobe, kneel at the edge of the ravine, and wait for the shot.

36

Babi Yar confirmed the precedent of Kamianets-Podilskyi for the destruction of Jews in central, eastern, and southern Ukrainian cities. Because Army Group South had captured Kiev late, and because news of German policies spread quickly, most Jews of these regions had fled east and therefore survived. Those who remained almost always did not. On 13 October 1941 about 12,000 Jews were killed at Dnipropetrovsk. The Germans were able to use the local administrations, established by themselves, to facilitate the work of gathering and then killing Jews. In Kharkiv, it appears that Sonderkommando 4a of Einsatzgruppe C had the city administration settle the remaining Jews in a single district. On 15 and 16 December more than 10,000 Kharkiv Jews were taken to a tractor factory at the edge of town. There they were shot in groups by Order Police Battalion 314 and Sonderkommando 4a in January 1942. Some of them were gassed in a truck that piped its own exhaust into its own cargo trailer, and thus into the lungs of Jews who were locked inside. Gas vans were also tried in Kiev, but rejected when the Security Police complained that they disliked removing mangled corpses covered with blood and excrement. In Kiev the German policemen preferred shooting over ravines and pits.

37

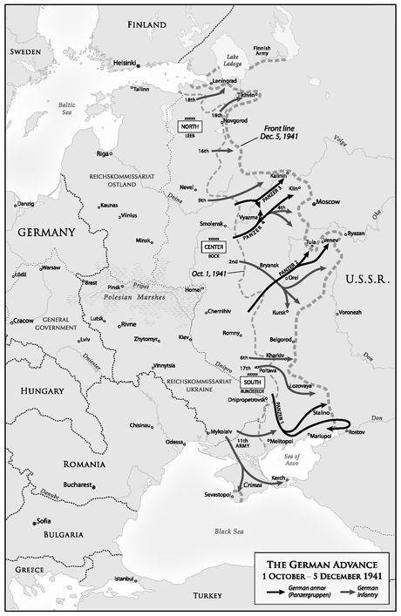

The timing of the mass murder was slightly different in occupied Soviet Belarus, behind the lines of Army Group Center. In the first eight weeks of the war, through August 1941, Einsatzgruppe B under Artur Nebe killed more Jews, in Vilnius and in Belarus, than any of the other Einsatzgruppen. But the further mass murder of Jews in Belarus was then delayed somewhat by a military consideration. Hitler decided to send divisions from Army Group Center to aid Army Group South in the battle for Kiev of September 1941. This decision of Hitler’s delayed the march of Army Group Center on Moscow, which was its main task.

38

Once Kiev was taken and the march on Moscow could resume, so did the killing. On 2 October 1941, Army Group Center began a secondary offensive on Moscow, code-named Operation Typhoon. Police and security divisions began to clear Jews from its rear. Army Group Center advanced with a force of 1.9 million men in seventy-eight divisions. Then the policy of general mass murder of Jews, including women and children, was extended throughout occupied Soviet Belarus. Throughout September 1941 Sonderkommando 4a and Einsatzkommando 5 of Einsatzgruppe B were already exterminating all Jews of villages and small towns. In early October that policy was applied to cities.

39

In October 1941, Mahileu became the first substantial city in occupied Soviet Belarus where almost all Jews were killed. A German (Austrian) policeman wrote to his wife of his feelings and experiences shooting the city’s Jews in the first days of the month. “During the first try, my hand trembled a bit as I shot, but one gets used to it. By the tenth try I aimed calmly and shot surely at the many women, children, and infants. I kept in mind that I have two infants at home, whom these hordes would treat just the same, if not ten times worse. The death that we gave them was a beautiful quick death, compared to the hellish torments of thousands and thousands in the jails of the GPU. Infants flew in great arcs through the air, and we shot them to pieces in flight, before their bodies fell into the pit and into the water.” On the second and third of October 1941, the Germans (with the help of auxiliary policemen from Ukraine) shot 2,273 men, women, and children at Mahileu. On 19 October another 3,726 followed.

40

Here in Belarus a direct order to kill women and children came from Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski, the Higher SS and Police Leader for “Russia Center,” the terrain behind Army Group Center. Bach, whom Hitler regarded as a “man who could wade through a sea of blood,” was the direct representative of Himmler, and was certainly acting in accordance with Himmler’s wishes. In occupied Soviet Belarus the accord between the SS and the army on the fate of the Jews was especially evident. General Gustav von Bechtolsheim, commander of the infantry division responsible for security in the Minsk area, fervently advocated the mass murder of Jews as a preventive measure. Had the Soviets invaded Europe, he was fond of saying, the Jews would have exterminated the Germans. Jews were “no longer humans in the European sense of the word,” and thus “must be destroyed.”

41

Himmler had endorsed the killing of women and children in July 1941, and then the total extermination of Jewish communities in August 1941, as a small taste of the paradise to come, the Garden of Eden that Hitler desired. It was a post-apocalyptic vision of exaltation after war, of life after death, the resurgence of one race after the extermination of others. Members of the SS shared the racism and the dream. The Order Police sometimes shared in this vision, and were of course corrupted by their own participation. The Wehrmacht officers and soldiers often held essentially the same views as the SS, girded by a certain interpretation of military practicality: that the elimination of the Jews could help bring an increasingly difficult war to a victorious conclusion, or prevent partisan resistance, or at least improve food supplies. Those who did not endorse the mass killing of Jews believed that they had no choice, since Himmler was closer to Hitler than they. Yet as time passed, even such military officers usually came to be convinced that the killing of Jews was necessary, not because the war was about to won, as Himmler and Hitler could still believe in summer 1941, but because the war could easily be lost.

42

Soviet power never collapsed. In September 1941, two months after the invasion, the NKVD was powerfully in evidence, directed against a most sensitive target: the Germans of the Soviet Union. By an order of 28 August, Stalin had 438,700 Soviet Germans deported to Kazakhstan in the first half of September 1941, most of them from an autonomous region in the Volga River. In its speed, competence, and territorial range, this one act of Stalin made a mockery of the confused and contradictory deportation actions that the Germans had carried out in the previous two years. It was at this moment of Stalin’s sharp defiance, in mid-September 1941, that Hitler took a strangely ambiguous decision: to send German Jews to the east. In October and November, the Germans began to deport German Jews to Minsk, Riga, Kaunas, and Łódź. Up to this point, German Jews had lost their rights and their property, but only rarely their lives. Now they were being sent, albeit without instructions to kill them, to places where Jews had been shot in large numbers. Perhaps Hitler wanted revenge. He could not have failed to notice that the Volga had not become Germany’s Mississippi. Rather than settling the Volga basin as triumphant colonists, Germans were being deported from it as repressed and humbled Soviet citizens.

43

Despair and euphoria were on intimate terms in Hitler’s mind, and so an entirely different interpretation is also possible. It is perfectly conceivable that Hitler began to deport German Jews because he wished to believe, or wished others to believe, that Operation Typhoon, the secondary offensive on Moscow that began on 2 October 1941, would bring the war to an end. In a moment of exaltation Hitler even claimed as much in a speech of 3 October: “The enemy is broken and will never rise again!” If the war was truly over, then the Final Solution, as a program of deportations for the postwar period, could begin.

44

Though Operation Typhoon brought no final victory, the Germans went ahead anyway with the deportations of German Jews to the east, which began a kind of chain reaction. The need to make room in these ghettos confirmed one mass killing method (in Riga, in occupied Latvia), and likely hastened the development of another (in Łódź, in occupied Poland).

In Riga, the police commander was now Friedrich Jeckeln, as Higher SS and Police Leader for Reichskommissariat Ostland. Jeckeln, a Riga native, had organized the first massive shooting of Jews at Kamianets-Podilskyi in August, in his former capacity as Higher SS and Police Leader for Reichskommissariat Ukraine. Now, after his transfer, he brought his industrial shooting methods to Latvia. First he had Soviet prisoners of war dig a series of pits in the Letbartskii woods, in the Rumbula Forest, near Riga. On a single day, 30 November 1941, Germans and Latvians marched some fourteen thousand Jews in columns to the shooting sites, forced them to lie down next to each other in pits, and shot them from above.

45