Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (36 page)

Read Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin Online

Authors: Timothy Snyder

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #European History, #Europe; Eastern - History - 1918-1945, #Political, #Holocaust; Jewish (1939-1945), #World War; 1939-1945 - Atrocities, #Europe, #Eastern, #Soviet Union - History - 1917-1936, #Germany, #Soviet Union, #Genocide - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Holocaust, #Massacres, #Genocide, #Military, #Europe; Eastern, #World War II, #Hitler; Adolf, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Massacres - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #20th Century, #Germany - History - 1933-1945, #Stalin; Joseph

The fate of some of the Soviet prisoners who were released from camps in the east suggested what was to come for the Jews. At Auschwitz in early September 1941, hundreds of Soviet prisoners were gassed with hydrogen cyanide, a pesticide (trade name Zyklon B) that had been used previously to fumigate the barracks of the Polish prisoners in the camp. Later, about a million Jews would be asphyxiated by Zyklon B at Auschwitz. At about the same time, other Soviet prisoners of war were used to test a gas van at Sachsenhausen. It pumped its own exhaust into its hold, thereby asphyxiating by carbon monoxide the people locked inside. That same autumn, gas vans would be used to kill Jews in occupied Soviet Belarus and occupied Soviet Ukraine. As of December 1941, carbon monoxide would also be used, in a parked gas van at Chełmno, to kill Polish Jews in lands annexed to Germany.

63

From among the terrorized and starving population of the prisoner-of-war camps, the Germans recruited no fewer than a million men for duties with the army and the police. At first, the idea was that they would help the Germans to control the territory of the Soviet Union after its government fell. When that did not happen, these Soviet citizens were assigned to assist in the mass crimes that Hitler and his associates pursued on occupied territory as the war continued. Many former prisoners were given shovels and ordered to dig trenches, over which the Germans would shoot Jews. Others were recruited for police formations, which were used to hunt down Jews. Some prisoners were sent to a training camp in Trawniki, where they learned to be guards. These Soviet citizens and war veterans, retrained to serve Nazi Germany, would spend 1942 in three death facilities in occupied Poland, Treblinka, Sobibór, and Bełżec, where more than a million Polish Jews would be gassed.

64

Thus some of the survivors of one German killing policy became accomplices in another, as a war to destroy the Soviet Union became a war to murder the Jews.

CHAPTER 6

FINAL SOLUTION

Hitler’s utopias crumbled upon contact with the Soviet Union, but they were refashioned rather than rejected. He was the Leader, and his henchmen owed their positions to their ability to divine and realize his will. When that will met resistance, as on the eastern front in the second half of 1941, the task of men such as Göring, Himmler, and Heydrich was to rearrange Hitler’s ideas such that Hitler’s genius was affirmed—along with their own positions in the Nazi regime. The utopias in summer 1941 had been four: a lightning victory that would destroy the Soviet Union in weeks; a Hunger Plan that would starve thirty million people in months; a Final Solution that would eliminate European Jews after the war; and a Generalplan Ost that would make of the western Soviet Union a German colony. Six months after Operation Barbarossa was launched, Hitler had reformulated the war aims such that the physical extermination of the Jews became the priority. By then, his closest associates had taken the ideological and administrative initiatives necessary to realize such a wish.

1

No lightning victory came. Although millions of Soviet citizens were starved, the Hunger Plan proved impossible. Generalplan Ost, or any variant of postwar colonization plans, would have to wait. As these utopias waned, political futures depended upon the extraction of what was feasible from the fantasies. Göring, Himmler, and Heydrich scrambled amidst the moving ruins, claiming what they could. Göring, charged with economics and the Hunger Plan, fared worst. Regarded as “the second man in the Reich” and as Hitler’s successor, Göring remained immensely prominent in Germany, but played an ever smaller role in the East. As economics became less a matter of grand planning for the postwar period and more a matter of improvising to continue the war, Göring lost his leading position to Albert Speer. Unlike Göring, Heydrich and Himmler were able to turn the unfavorable battlefield situation to their advantage, by reformulating the Final Solution so that it could be carried out during a war that was not going according to plan. They understood that the war was becoming, as Hitler began to say in August 1941, a “war against the Jews.”

2

Himmler and Heydrich saw the elimination of the Jews as their task. On 31 July 1941 Heydrich secured the formal authority from Göring to formulate the Final Solution. This still involved the coordination of prior deportation schemes with Heydrich’s plan of working the Jews to death in the conquered Soviet East. By November 1941, when Heydrich tried to schedule a meeting at Wannsee to coordinate the Final Solution, he still had such a vision in mind. Jews who could not work would be made to disappear. Jews capable of physical labor would work somewhere in the conquered Soviet Union until they died. Heydrich represented a broad consensus in the German government, though his was not an especially timely plan. The Ministry for the East, which oversaw the civilian occupation authorities established in September, took for granted that the Jews would disappear. Its head, Alfred Rosenberg, spoke in November of the “biological eradication of Jewry in Europe.” This would be achieved by sending the Jews across the Ural Mountains, Europe’s eastern boundary. But by November 1941 a certain vagueness had descended upon Heydrich’s vision of enslavement and deportation, since Germany had not destroyed the Soviet Union and Stalin still controlled the vast majority of its territory.

3

While Heydrich made bureaucratic arrangements in Berlin, it was Himmler who most ably extracted the practical and the prestigious from Hitler’s utopian thinking. From the Hunger Plan he took the categories of surplus populations and useless eaters, and would offer the Jews as the people from whom calories could be spared. From the lightning victory he extracted the four Einsatzgruppen. Their task had been to kill Soviet elites in order to hasten the Soviet collapse. Their first mission had not been to kill all Jews as such. The Einsatzgruppen had no such order when the invasion began, and their numbers were too small. But they had experience killing civilians, and they could find local help, and they could be reinforced. From Generalplan Ost, Himmler extracted the battalions of Order Police and thousands of local collaborators, whose preliminary assignment was to help control the conquered Soviet Union. Instead they provided the manpower that allowed the Germans to carry out truly massive shootings of Jews beginning in August 1941. These institutions, supported by the Wehrmacht and its Field Police, allowed the Germans to murder about a million Jews east of the Molotov-Ribbentrop line by the end of the year.

4

Himmler succeeded because he grasped extremes of the Nazi utopias that operated within Hitler’s mind, even as Hitler’s will faced the most determined resistance from the world outside. Himmler made the Final Solution more radical, by bringing it forward from the postwar period to the war itself, and by showing (after the failure of four previous deportation schemes) how it could be achieved: by the mass shooting of Jewish civilians. His prestige suffered little from the failures of the lightning victory and the Hunger Plan, which were the responsibility of the Wehrmacht and the economic authorities. Even as he moved the Final Solution into the realm of the realizable, he still nurtured the dream of the Generalplan Ost, Hitler’s “Garden of Eden.” He continued to order revisions of the plan, and arranged an experimental deportation in the Lublin district of the General Government, and would, as opportunities presented themselves, urge Hitler to raze cities.

5

In the summer and autumn of 1941, Himmler ignored what was impossible, pondered what was most glorious, and did what could be done: kill the Jews east of the Molotov-Ribbentrop line, in occupied eastern Poland, the Baltic States, and the Soviet Union. Aided by this realization of Nazi doctrine during the months when German power was challenged, Himmler and the SS would come to overshadow civilian and military authorities in the occupied Soviet Union, and in the German empire. As Himmler put it, “the East belongs to the SS.”

6

The East, until very recently, had belonged to the NKVD. One secret of Himmler’s success was that he was able to exploit the legacy of Soviet power in the places where it had most recently been installed.

In the first lands that German soldiers reached in Operation Barbarossa, they were the war’s second occupier. The first German gains in summer 1941 were the territories Germans had granted to the Soviets by the Treaty on Borders and Friendship of September 1939: what had been eastern Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, annexed in the meantime to the Soviet Union. In other words, in Operation Barbarossa German troops first entered lands that had been independent states through 1939 or 1940, and only then entered the prewar Soviet Union. Their Romanian ally meanwhile conquered the territories that it had lost to the Soviet Union in 1940.

7

The double occupation, first Soviet, then German, made the experience of the inhabitants of these lands all the more complicated and dangerous. A single occupation can fracture a society for generations; double occupation is even more painful and divisive. It created risks and temptations that were unknown in the West. The departure of one foreign ruler meant nothing more than the arrival of another. When foreign troops left, people had to reckon not with peace but with the policies of the next occupier. They had to deal with the consequences of their own previous commitments under one occupier when the next one came; or make choices under one occupation while anticipating another. For different groups, these alternations could have different meanings. Gentile Lithuanians (for example) could experience the departure of the Soviets in 1941 as a liberation; Jews could not see the arrival of the Germans that way.

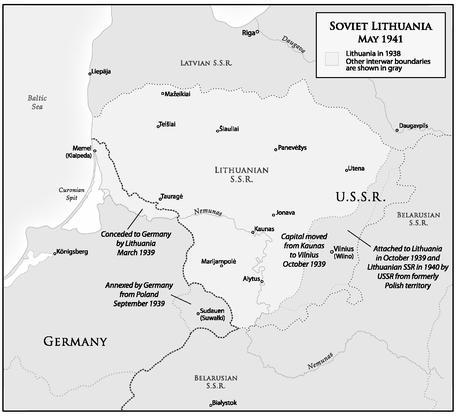

Lithuania had already undergone two major transformations by the time that German troops arrived in late June 1941. Lithuania, while still an independent state, had appeared to benefit from the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939. The Treaty on Borders and Friendship of September 1939 had granted Lithuania to the Soviets, but Lithuanians had no way of knowing that. What the Lithuanian leadership perceived that month was something else: Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union destroyed Poland, which throughout the interwar period had been Lithuania’s adversary. The Lithuanian government had considered Vilnius, a city in interwar Poland, as its capital. Lithuania, without taking part in any hostilities in September 1939, gained Polish lands for itself. In October 1939, the Soviet Union granted Lithuania Vilnius and the surrounding regions (2,750 square miles, 457,500 people). The price of Vilnius and other formerly Polish territories was basing rights for Soviet soldiers.

8

Then, just half a year after Lithuania had been enlarged thanks to Stalin, it was conquered by its seeming Soviet benefactor. In June 1940 Stalin seized control of Lithuania and the other Baltic States, Latvia and Estonia, and hastily incorporated them into the Soviet Union. After this annexation, the Soviet Union deported about twenty-one thousand people from Lithuania, including many Lithuanian elites. A Lithuanian prime minister and a Lithuanian foreign minister were among the exiled thousands. Some Lithuanian political and military leaders escaped the Gulag by fleeing to Germany. These were often people with some prior connections in Berlin, and always people embittered by their experience with Soviet aggression. The Germans favored the right-wing nationalists among the Lithuanian émigrés, and trained some of them to take part in the invasion of the Soviet Union.

9

Thus when the Germans invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Lithuania occupied a unique position. It had profited from the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact; then it had been conquered by the Soviets; now it would be occupied by the Germans. After the ruthless year of Soviet occupation, many Lithuanians welcomed this change; few Lithuanian Jews were among them. Two hundred thousand Jews lived in Lithuania in June 1941 (about the same number as in Germany). The Germans arrived in Lithuania with their handpicked nationalist Lithuanians and encountered local people who were willing to believe, or to act as if they believed, that Jews were responsible for Soviet repressions. The Soviet deportations had taken place that very month, and the NKVD had shot Lithuanians in prisons just a few days before the Germans arrived. The Lithuanian diplomat Kazys Škirpa, who returned with the Germans, used this suffering in his radio broadcasts to spur mobs to murder. Some 2,500 Jews were killed by Lithuanians in bloody pogroms in early July.

10