Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (71 page)

Read Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin Online

Authors: Timothy Snyder

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #European History, #Europe; Eastern - History - 1918-1945, #Political, #Holocaust; Jewish (1939-1945), #World War; 1939-1945 - Atrocities, #Europe, #Eastern, #Soviet Union - History - 1917-1936, #Germany, #Soviet Union, #Genocide - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Holocaust, #Massacres, #Genocide, #Military, #Europe; Eastern, #World War II, #Hitler; Adolf, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Massacres - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #20th Century, #Germany - History - 1933-1945, #Stalin; Joseph

Each of the dead became a number. Between them, the Nazi and Stalinist regimes murdered more than fourteen million people in the bloodlands. The killing began with a political famine that Stalin directed at Soviet Ukraine, which claimed more than three million lives. It continued with Stalin’s Great Terror of 1937 and 1938, in which some seven hundred thousand people were shot, most of them peasants or members of national minorities. The Soviets and the Germans then cooperated in the destruction of Poland and of its educated classes, killing some two hundred thousand people between 1939 and 1941. After Hitler betrayed Stalin and ordered the invasion of the Soviet Union, the Germans starved the Soviet prisoners of war and the inhabitants of besieged Leningrad, taking the lives of more than four million people. In the occupied Soviet Union, occupied Poland, and the occupied Baltic States, the Germans shot and gassed some 5.4 million Jews. The Germans and the Soviets provoked one another to ever greater crimes, as in the partisan wars for Belarus and Warsaw, where the Germans killed about half a million civilians.

These atrocities shared a place, and they shared a time: the bloodlands between 1933 and 1945. To describe their course has been to introduce to European history its central event. Without an account of all of the major killing policies in their common European historical setting, comparisons between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union must be inadequate. Now that this history of the bloodlands is complete, the comparison remains.

The Nazi and the Stalinist systems must be compared, not so much to understand the one or the other but to understand our times and ourselves. Hannah Arendt made this case in 1951, uniting the two regimes under the rubric of “totalitarianism.” Russian literature of the nineteenth century offered her the idea of the “superfluous man.” The pioneering Holocaust historian Raul Hilberg later showed her how the bureaucratic state could eradicate such people in the twentieth century. Arendt provided the enduring portrait of the modern superfluous man, made to feel so by the crush of mass society, then made so by totalitarian regimes capable of placing death within a story of progress and joy. It is Arendt’s portrayal of the killing epoch that has endured: of people (victims and perpetrators alike) slowly losing their humanity, first in the anonymity of mass society, then in a concentration camp. This is a powerful image, and it must be corrected before a historical comparison of Nazi and Soviet killing can begin.

1

The killing sites that most closely fit such a framework were the German prisoner-of-war camps. They were the only type of facility (German or Soviet) where the purpose of concentrating human beings was to kill them. Soviet prisoners of war, crushed together in the tens of thousands and denied food and medical care, died quickly and in great numbers: some three million perished, most of them in a few months. Yet this major example of killing by concentration had little to do with Arendt’s concept of modern society. Her analysis directs our attention to Berlin and Moscow, as the capitals of distinct states that exemplify the totalitarian system, each of them acting upon their own citizens. Yet the Soviet prisoners of war died as a result of the

interaction

of the two systems. Arendt’s account of totalitarianism centers on the dehumanization

within

modern mass industrial society, not on the historical overlap

between

German and Soviet aspirations and power. The crucial moment for these soldiers was their capture, when they passed from the control of their Soviet superior officers and the NKVD to that of the Wehrmacht and the SS. Their fate cannot be understood as progressive alienation within one modern society; it was a consequence of the belligerent encounter of two, of the criminal policies of Germany on the territory of the Soviet Union.

Elsewhere, concentration was not usually a step in a killing process but rather a method for correcting minds and extracting labor from bodies. With the important exception of the German prisoner-of-war camps, neither the Germans nor the Soviets intentionally killed by concentration. Camps were more often the alternative than the prelude to execution. During the Great Terror in the Soviet Union, two verdicts were possible: death or the Gulag. The first meant a bullet in the nape of the neck. The second meant hard labor in a faraway place, in a dark mine or a freezing forest or on the open steppe; but it also usually meant life. Under German rule, the concentration camps and the death factories operated under different principles. A sentence to the concentration camp Belsen was one thing, a transport to the death factory Bełżec something else. The first meant hunger and labor, but also the likelihood of survival; the second meant immediate and certain death by asphyxiation. This, ironically, is why people remember Belsen and forget Bełżec.

Nor did extermination policies arise from concentration policies. The Soviet concentration camp system was an integral part of a political economy that was meant to endure. The Gulag existed before, during, and after the famines of the early 1930s, and before, during, and after the shooting operations of the late 1930s. It reached its largest size in the early 1950s, after the Soviets had ceased to kill their own citizens in large numbers—in part for that very reason. The Germans began the mass killing of Jews in summer 1941 in the occupied Soviet Union, by gunfire over pits, far from a concentration camp system that had already been in operation for eight years. In a matter of a given few days in the second half of 1941, the Germans shot more Jews in the east than they had inmates in all of their concentration camps. The gas chambers were not developed for concentration camps, but for the medical killing facilities of the “euthanasia” program. Then came the mobile gas vans used to kill Jews in the Soviet east, then the parked gas van at Chełmno used to kill Polish Jews in lands annexed to Germany, then the permanent gassing facilities at Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka in the General Government. The gas chambers allowed the policy pursued in the occupied Soviet Union, the mass killing of Jews, to be continued west of the Molotov-Ribbentrop line. The vast majority of Jews killed in the Holocaust never saw a concentration camp.

2

The image of the German concentration camps as the worst element of National Socialism is an illusion, a dark mirage over an unknown desert. In the early months of 1945, as the German state collapsed, the chiefly non-Jewish prisoners in the SS concentration camp system were dying in large numbers. Their fate was much like that of Gulag prisoners in the Soviet Union between 1941 and 1943, when the Soviet system was stressed by the German invasion and occupation. Some of the starving victims were captured on film by the British and the Americans. These images led west Europeans and Americans toward erroneous conclusions about the German system. The concentration camps did kill hundreds of thousands of people at the end of the war, but they were not (in contrast to the death facilities) designed for mass killing. Although some Jews were sentenced to concentration camps as political prisoners and others were dispatched to them as laborers, the concentration camps were not chiefly for Jews. Jews who were sent to concentration camps were among the Jews who survived. This is another reason the concentration camps are familiar: they were described by survivors, people who would have been worked to death eventually, but who were liberated at war’s end. The German policy to kill all the Jews of Europe was implemented not in the concentration camps but over pits, in gas vans, and at the death facilities at Chełmno, Bełżec, Sobibór, Treblinka, Majdanek, and Auschwitz.

3

As Arendt recognized, Auschwitz was an unusual combination of an industrial camp complex and a killing facility. It stands as a symbol of both concentration and extermination, which creates a certain confusion. The camp first held Poles, and then Soviet prisoners of war, and then Jews and Roma. Once the death factory was added, some arriving Jews were selected for labor, worked until exhaustion, and then gassed. Thus chiefly at Auschwitz can an example be found of Arendt’s image of progressive alienation ending with death. It is a rendering that harmonizes with the literature of Auschwitz written by its survivors: Tadeusz Borowski, or Primo Levi, or Elie Wiesel. But this sequence is exceptional. It does not capture the usual course of the Holocaust, even at Auschwitz. Most of the Jews who died at Auschwitz were gassed upon arrival, never having spent time inside a camp. The journey of Jews from the camp to the gas chambers was a minor part of the history of the Auschwitz complex, and is misleading as a guide to the Holocaust or to mass killing generally.

Auschwitz was indeed a major site of the Holocaust: about one in six murdered Jews perished there. But though the death factory at Auschwitz was the last killing facility to function, it was not the height of the technology of death: the most efficient shooting squads killed faster, the starvation sites killed faster, and Treblinka killed faster. Auschwitz was also not the main place where the two largest Jewish communities in Europe, the Polish and the Soviet, were exterminated. Most Soviet and Polish Jews under German occupation had already been murdered by the time Auschwitz became the major death factory. By the time the gas chamber and crematoria complexes at Birkenau came on line in spring 1943, more than three quarters of the Jews who would be killed in the Holocaust were already dead. For that matter, the tremendous majority of all of the people who would be deliberately killed by the Soviet and the Nazi regimes, well over ninety percent, had already been killed by the time those gas chambers at Birkenau began their deadly work. Auschwitz is the coda to the death fugue.

Perhaps, as Arendt argued, Nazi and Soviet mass murder was a sign of some deeper dysfunctionality of modern society. But before we draw such theoretical conclusions, about modernity or anything else, we must understand what actually happened, in the Holocaust and in the bloodlands generally. For the time being, Europe’s epoch of mass killing is overtheorized and misunderstood.

Unlike Arendt, who was extraordinarily knowledgeable within the limits of the available documentation, we have little excuse for this disproportion of theory to knowledge. The numbers of the dead are now available to us, sometimes more precisely, sometimes less, but firmly enough to convey a sense of the destructiveness of each regime. In policies that were meant to kill civilians or prisoners of war, Nazi Germany murdered about ten million people in the bloodlands (and perhaps eleven million people total), the Soviet Union under Stalin over four million in the bloodlands (and about six million total). If foreseeable deaths resulting from famine, ethnic cleansing, and long stays in camps are added, the Stalinist total rises to perhaps nine million and the Nazi to perhaps twelve. These larger numbers can never be precise, not least because millions of civilians who died as an indirect result of the Second World War were victims, in one way or another, of

both

systems.

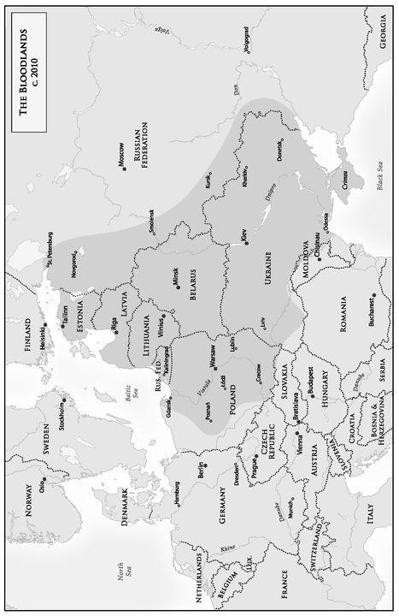

The region most touched by both the Nazi and Stalinist regimes was the bloodlands: in today’s terms, St. Petersburg and the western rim of the Russian Federation, most of Poland, the Baltic States, Belarus, and Ukraine. This is where the power and the malice of the Nazi and Soviet regimes overlapped and interacted. The bloodlands are important not only because most of the victims were its inhabitants but also because it was the center of the major policies that killed people from elsewhere. For example, the Germans killed about 5.4 million Jews. Of those, more than four million were natives of the bloodlands: Polish, Soviet, Lithuanian, and Latvian Jews. Most of the remainder were Jews from other east European countries. The largest group of Jewish victims from beyond the region, the Hungarian Jews, were killed in the bloodlands, at Auschwitz. If Romania and Czechoslovakia are also considered, then east European Jews account for nearly ninety percent of the victims of the Holocaust. The smaller Jewish populations of western and southern Europe were deported to the bloodlands to die.

Like the Jewish victims, the non-Jewish victims either were native to the bloodlands or were brought there to die. In their prisoner-of-war camps and in Leningrad and other cities, the Germans starved more than four million people to death. Most but not all of the victims of these deliberate starvation policies were natives of the bloodlands; perhaps a million were Soviet citizens from beyond the region. The victims of Stalin’s policies of mass murder lived across the length and breadth of the Soviet Union, the largest state in the history of the world. Even so, Stalin’s blow fell hardest in the western Soviet borderlands, in the bloodlands. The Soviets starved more than five million people to death during collectivization, most of them in Soviet Ukraine. The Soviets recorded the killing of 681,691 people in the Great Terror of 1937-1938, of whom a disproportionate number were Soviet Poles and Soviet Ukrainian peasants, two groups that inhabited the western Soviet Union, and thus the bloodlands. These numbers do not themselves constitute a comparison of the systems, but they are a point of departure, perhaps an obligatory one.

4