Book of Fire (52 page)

Throckmorton feared that when Pole ‘rode out as usual with five or six horses unarmed’, Phillips could destroy him ‘with the help of three or four hardy fellows’ and escape to the mountains –

‘this is the Italians’ practice, or poison’. Pole and Throckmorton persuaded the Venetians to force Phillips to quit their territory; Tebold reported that they were so thoroughly afraid of Phillips that ‘every wagging of a straw maketh them now afraid’.

Phillips himself approached Tebold for help, ‘pretending great repentance’. He claimed to be ‘so troubled and dismayed that half his life was gone’. Tebold refused to give him money. Desperately short of cash, Phillips sold his doublet of velvet and damask, and his cloak of English cloth. Tebold advised him to sue for pardon and grace in England, and he said he would return and submit himself.

Phillips was back in Flanders early in 1539, and seemingly contrite. The new English ambassador in Brussels, Sir Thomas Wriothesley, wrote in high excitement to Cromwell on 5 February 1539. ‘I trust by tomorrow night to have Henry Phillips yield himself to me as the King’s prisoner, or else lay him fast,’ he wrote. ‘If he come I shall send him to England, and for my word’s sake, be a suitor for his pardon.’ Wriothesley said that a repentant Phillips would be an ideal agent for the crown, ‘as his language in many tongues is excellent and his experience great’.

All appeared to go well. On 7 February, Wriothesley reported to Cromwell that Phillips ‘hath submitted himself to me as the King’s minister’. The ambassador did not interrogate him – ‘I forebore to examine him here, fearing that delay and curiousness in examination might frighten him’ – but was confident that Phillips would ‘perform what he has promised me’. He said that he had at first refused to shake Phillips’s hand, at which Phillips had knelt before him. ‘Sir,’ Phillips said, ‘I come to submit myself wholly to the King’s Majesty’s mercy. I have so offended that I am unworthy to live, yet perhaps report has made my doings seem worse than they were …’ Wriothesley warned him that a liar would deserve no mercy, but the king was a most merciful prince, and Phillips might be pardoned by ‘telling the whole truth of thy life since thou hast

been of this naughty sort’. Phillips ‘promised to follow my advice’, and the ambassador bid him stand and, trustingly, shook him by the hand. He was charmed by Phillips. ‘The fellow hath great wit,’ he wrote to Cromwell. ‘He is excellent in languages … he hath freely yielded himself, thinking it better to be hanged than to live like a traitor.’

The two men bid each other goodnight. It was agreed that Phillips would leave for England the next morning. He was given a chamber in Wriothesley’s house for the night, with two men to ‘keep him in sight until he was on horseback in the morning’.

Between 6 and 7 a.m. the next morning, 8 February, Phillips disappeared. So did ‘more or less to 2000 crowns of the sun’, and some rings and jewellery belonging to the ambassador, to a total value of 2400 crowns. ‘I sent out my horse every way, sent men to the seven gates here to watch for him,’ Wriothesley wrote on 9 February. ‘There was such running and riding and stirring about the town as has not been seen these hundred years.’ The ambassador offered a reward of 1000 gold guilders to any who brought Phillips back to him, and 100 crowns for information that led to his capture. Wriothesley railed and fumed – ‘Mr W takes his escape so heavily,’ an acquaintance wrote, ‘that I fear a return of his ague’ – to no effect. Phillips was gone.

In April 1539, he was reported to be in the service of the duke of Cleves. His name was included in a Bill of Attainder of 28 April 1539, as ‘having traitrously maintained the pope’s headship of the church of England’. He was later sighted in Italy.

Sir Thomas Seymour, writing to Henry VIII from the camp of the king of Hungary outside Buda, on 8 August 1542, reported that Phillips was in danger of having his eyes put out. Phillips had been in Vienna, where he had confessed to an Englishman ‘that he hath been ambassador for the Turk divers time by the space of V [five] years’. This made him a traitor to the Hungarian king, and in peril of losing his eyes or his life. He appears to have escaped

again, but the trail goes cold on the Hungarian plain. No more is heard of him, other than Foxe’s final comment that, or ‘the saying so goeth’, having lived from the blood of others, Phillips was finally ‘consumed at last with lice’.

Thomas Poyntz from the English House suffered poverty and the break-up of his family for his loyalty to Tyndale. He petitioned the king in 1536, having been ‘banished the Emperor’s countries for matters of religion, and repaired to England’, for the restoration of his son Fardinando Poyntz to him. Poyntz had placed the boy in a school in Burton upon Trent, but the lad had been taken away ‘by the petitioner’s wife, who remains apart from him in Antwerp’. He died in 1562 and is fondly remembered by a Latin epitaph near his tomb. It praises his ‘ardent profession of evangelical truth’ for which he ‘suffered bonds and imprisonment beyond the sea, and would plainly have been destined to death, had he not, trusting in divine providence, saved himself in a wonderful manner by breaking his prison. In this chapel he now sleeps peacefully in the Lord, 1562.’

Stokesley, the bishop of London, remained hostile to the English Bible. Archbishop Cranmer divided Tyndale’s New Testament into ‘portions’ which he distributed to the ‘best learned bishops’ so that they could correct any errors. Stokesley was assigned Acts. He refused even to read it. ‘I marvaile what my lorde of Canterbury meaneth,’ he wrote, ‘that thus abuseth the people in gyvyng them libertie to reade the scriptures, which doith nothing else but infecte them with herysies. I have bestowed never an hower apon my portion, nor never will.’ He also continued to oppose clerical marriage; he told a married priest that he ‘had better have a hundred whores than be married to his own wife’.

But he fell in with Cromwell’s regime happily enough. When colleagues of the martyred monks of the Charterhouse continued to mutter against the royal supremacy, Cromwell’s agent Sir John

Whalley suggested that reliable and amenable bishops such as Stokesley should preach to them. Stokesley duly won the monks over, and in January 1536, under his supervision, they wrote that they had been persuaded to submit to the crown not by ‘fear of bodily pain, penury or death’ but by ‘duty informed and ordered …’. Stokesley and Cranmer administered the Oath of Supremacy to them a few days later. Stokesley was no rebel or risk-taker. He died in 1539 and was buried before the altar of the Lady Chapel in St Paul’s, the cathedral having been draped in black cloth from the west door to the high altar.

Stephen Vaughan survived the dangers of his times and calling. After missions to France and Germany, in 1536 he was employed to spy on Queen Catherine in her retirement from court to Kimbolton Castle in Huntingdonshire. Vaughan was rewarded with a permanent post at the Mint from 1537, and with a grant of Church lands in 1544. He died as the well-respected Member of Parliament for Lancaster in 1549.

George Constantine remained a betrayer. He returned to England at a date before 1536 and became vicar of Llawhaden in Pembrokeshire, and was later registrar of St David’s diocese. In 1554, after the Catholic Queen Mary came to the throne, Constantine was one of those who accused the bishop of St David’s, Robert Ferrar, of heresy. Ferrar was burnt the following year ‘for the example and terror of such as he seduced and mis-taught’. Constantine took a wife – his daughter married a future archbishop of York – before his own death in 1559.

Nicholas Udall, survivor of the Oxford fish cellar, versifier and headmaster, was dismissed from Eton in 1541 for complicity in the theft of valuable silver images and college plate, and conduct unbecoming, and was imprisoned in the Marshalsea.

Thomas Cromwell went on to issue injunctions in 1536 and 1538 that every church should be provided with a Bible. He arranged the dissolution of the monasteries between 1536 and

1540, benefiting personally from confiscated estates. Conservative intrigues, and his arrangement of the marriage between Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves, whom the startled monarch described as ‘a Flemish mare’, cost him his head in 1540. Henry himself survived until 1547.

As to Sir Thomas More, posterity has treated him well. His general revelry in the stake and the fire, and his individual and obsessive hatred of William Tyndale, are largely forgotten. He progressed smoothly from beatification in 1886 to canonisation in 1935, sharing a feast day, 22 June, with the fiery bishop of Rochester, Saint John Fisher. He is plentifully honoured, in the names of schools, colleges, housing estates, and streets, by statues and monuments, and by the film,

A Man for All Seasons

.

John Paul II did him the ultimate honour on 31 October 2000, proclaiming him to be the patron saint of politicians. The pope’s motive, so Cardinal Roger Etchegaray explained, was to remind politicians ‘of the absolute priority of God in the heart of public affairs’. But is it wise – is it Christian? – to remind politicians of a man who held his incinerated opponents to be ‘well and worthily burned’?

Tyndale’s honours are less obvious. He is unsainted, of course, and few Anglican churches keep his feast day, October 6; his statues and memorials – on a slope of the Cotswolds, by the Victoria Embankment in London, in a car park in Vilvoorde – are obscure compared to those of his great enemy. But his life’s work triumphed. His ploughboy soon had his English Bible.

In 1535, Miles Coverdale had published the first complete English Bible, dedicated to Henry VIII, and probably printed at Zurich. Coverdale based this on Tyndale and the Vulgate, translating the outstanding Old Testament books from Luther and Zwingli, and with reference to the Vulgate.

‘Matthew’s Bible’, so called because its title page claimed it to be ‘truly and purely translated by Thomas Matthew’, the alias of John Rogers, was printed at Antwerp in 1537. It was dedicated to the king, who licensed 1500 copies. These were for legal sale in England and for general reading for the first time. Rogers, martyred at Smithfield under Queen Mary, was the chaplain to the English merchants at Antwerp and Tyndale’s friend. He used Tyndale’s New Testament, and Pentateuch, and other Old Testament books, from Joshua to 2 Chronicles, with the remaining OT books from Coverdale. The initials ‘W. T.’ between the two testaments recognise it as being predominantly Tyndale’s work.

Other Bibles followed. Copies of the ‘Great Bible’, printed under Thomas Cromwell’s patronage at Paris in 1539, were placed in all the churches of England. A definitive Tyndale Testament – ‘after the last copye corrected by his lyfe’ – was ‘imprynted at London by Richard Iugge, dwellynge in Paules churchyarde, at the signe of the Bible An. M.D.xlviii’. It seems fitting of Tyndale’s ultimate triumph that the first English printer to put his name to a Tyndale testament, in 1548, should have lived where so many Tyndale bibles had been burnt.

The ‘Geneva Bible’ of 1560 was also known as the ‘Breeches’ Bible’, for translating a phrase in Genesis as ‘they made themselves breeches’ instead of ‘aprons’. It had the full elaboration of the printer’s art: maps, tables, concordances, prefaces, illustrations, and marginal notes and glosses. The ‘Douai-Reims Bible’ of 1582 and 1610 were, ironically, Roman Catholic translations.

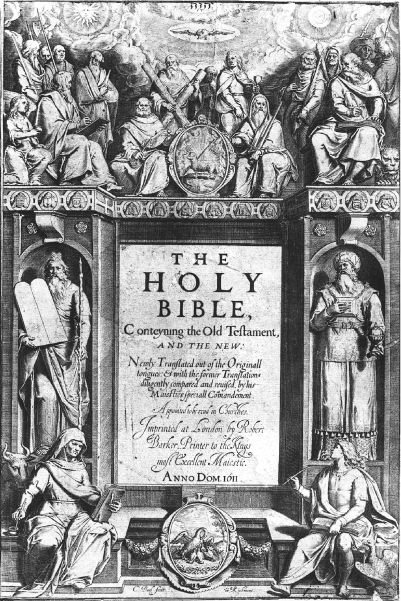

Tyndale’s genius was ultimately enshrined in the great ‘Authorised Version’ or ‘King James’ Bible. A body of fifty-four translators – all but one of them ordained – was appointed by James I to produce a new version. They were divided into six companies, two meeting at Westminster under the dean, and two apiece at Oxford and Cambridge under the direction of their

professors of Hebrew. They completed their work in 1611. Within a generation, it had displaced all its competitors. With its revisions, the Revised Version of 1881–5 and the American Standard Version of 1901, it has remained the most familiar – to many, the only – English Bible.

The title page of the King James Bible of 1611. Little of it was, as claimed, ‘Newly Translated out of the Originall Tongues’. It serves rather as Tyndale’s undying memorial. More than four-fifths of the New Testament is directly his, and three-quarters of the Old Testament books that he translated.

(Hulton Getty)

It is, as we have seen, overwhelmingly Tyndale’s Bible. Almost any passage in the New, and most in the Old Testament, can serve as his memorial. Let us take the opening of John’s gospel as our example:

In the begynnynge was the worde, [writes Tyndale], and the worde was with God: and the word was God. The same was in the begynnynge wyth God. All thinges were made by it and with out it was made nothinge that was made. In it was lyfe and the lyfe was the lyght of men. And the light shyneth in the darknes but the darknes comprehended it not.

In the beginning was the word, [echo King James’s fifty-four divines], and the word was with God, and the word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him, and without him was not any thing made that was made. In him was life and the life was the light of men. And the light shineth in darknesse, and the darknesse comprehended it not.