Book of Fire (51 page)

The last to be heard of him, while Tyndale was still alive, was that he had made his way from Rome to Paris. Here he was discovered, ‘all ragged and torn’, by an Oxford friend who found him clothes and lodging. True to form, Phillips rewarded this generosity by stealing from his benefactor.

At the last in Vilvoorde, so Foxe wrote, Tyndale ‘prayed that he might have some English divines come unto him: for the manners and ceremonies in religion in Dutchland (said he) did much differ from manners and ceremonies used in England’. It added that ‘divers divines from Louvain, whereof some were Englishmen’ were sent to him; other Catholic refugees had fled from England to join Phillips and Buckenham in Louvain. The note closes abruptly: ‘and after many examinations at the last they condemned him’.

Tyndale was found guilty of heresy in the first days of August 1536. He was told that he was to be degraded from the priesthood and relaxed to the secular power for sentence. John Hutton, the government agent in the Low Countries, wrote to Cromwell from Antwerp on 12 August to say that he had dined with the procurer general in the English House two days before. The official ‘certified to me that William Tyndale is degraded, and condemned into the hands of the secular power, so that he is very likely to suffer death this next week’. Hutton said that he had been unable to learn the articles on which Tyndale had been condemned; he promised that when he had the details, they ‘shall be sent to your lordship by the first’.

The degradation – or unhallowing, in which the disgraced man was ceremoniously stripped of his priestly dignity – almost certainly took place after 5 August and before Hutton’s dinner engagement on 10 August. A deed was signed in The Falcon Inn

at Vilvoorde on 5 August in which the inquisitor general for the Low Countries, Jacques de Lattre, delegated his powers to Ruard Tapper. The deed was witnessed by Latomus and by the other theologian in the case, Jan Doye. The way was now clear for Tapper to authorise the ceremony with Pierre Dufief, the procurer general.

Dufief submitted the expenses he ran up in staging the ‘unhallowing of Guillem Tindal, an Englishman’. They came to some £19 – the authorities paid them promptly at the end of the month – and covered the cost of hiring carriages for visiting dignitaries, and for fees for ‘the serjeants and servants of the town’. The interrogations and trial had been carried out in secret, but the degradation was a public spectacle, staged to strike fear into heretical hearts. It was carried out, so Dufief’s expenses record, by ‘the bishop suffragan and the two prelates assisting him … while other ecclesiastics and laymen were present’.

The ceremony may have been held in the main church of Vilvoorde, or on the large square in front of it, little more than 200 yards across the stagnant moat from the castle where Tyndale had his cell. Protocol demanded that the inquisitor general and his secretary, Willem van Caverschoen, be present together with the Louvain canons and the other commissioners from the case. An event of this drama will have attracted spectators from across the region, encouraged by their parish priests, anxious that their flock witness the humbling of the new religion. The inquisition had a fine sense of theatre; it transformed burnings and humiliations into

autos-da-fé

, acts of faith, in which ritual and entertainment blended into a living morality play in which a mass audience watched heretics pay the price for their evil.

The process was unchanged from the days of John Huss. The three bishops – the suffragan was from Cambrai – were seated on a high wooden platform. Tyndale was led to it, in the vestments of a priest about to celebrate mass, and made to kneel in front of the

bishops. His hands were scraped with the blade of a knife, symbolically removing the oil with which he had been anointed at his consecration. The sacraments were placed in his hands and taken away. As the cup was removed from him, the bishops intoned a solemn curse: ‘O cursed Judas, because you have abandoned the counsel of peace and have counselled with the Jews, we take away from you this cup of redemption.’ Other curses were pronounced as his stole and chasuble were stripped from him, one by one, and he was reclothed as a layman.

At the end, the bishops intoned the final curse: ‘We commit your soul to the devil.’ Having deprived him of all ecclesiastical rights, the bishops then ensured that the Church would not be stained with Tyndale’s blood by proclaiming: ‘We turn him over to the secular court.’ Ritual demanded that Dufief acknowledge this by saying: ‘I am the one who wields the temporal sword.’ Tyndale was now doubly condemned. The

poena sensus

was to be achieved by his strangulation and burning; this was to be followed by the

poena damni

, confirming his absolute separation from God in the eternity of hell.

Hutton expected that Tyndale would die within the week. Instead, he lived for two more months. We do not know the reason for the delay, but the Dominicans and priests assigned to the prisoner will have used the time to try to persuade him to recant. A condemned man who reconciled himself to the Church saved his immortal soul, if not his life and body; and a coterie of monks accompanied him to the stake in the hope of a last-minute change of heart. When a prisoner accepted the faith at Logrono in Spain, as the torch was waved before his eyes, the Dominicans attending him, in the moments before his pyre was lit, ‘began to embrace him with tenderness and gave infinite thanks to God for having opened to them a door for his conversion …’. Tyndale denied his interrogators the famous victory they sought. He

reminded himself no doubt of the advice that he had given to Frith in the same circumstances; to ‘cleave fast to the rock of the help of God, and commit the end of all things to him’, and, when the friars tempted him to abjure, to ‘be not overcome of men’s persuasions’.

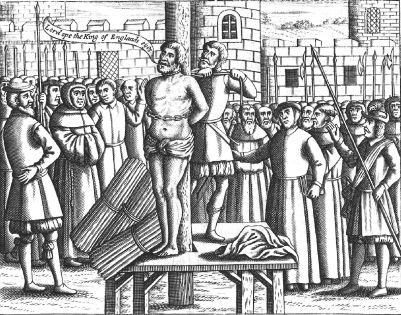

The executioner strangles Tyndale moments before burning him at the stake in Vilvoorde. His last words – ‘Lord ope the King of Englands eyes’‘ – became part of Protestant mythology. Contemporaries noted no such words, however, only that the strangling was bungled and that he suffered terribly.

(Hulton Getty)

He was executed early in October 1536, probably before noon on 6 October. A stout stake or beam was set up in a public place, perhaps in the main town square between the church and the castle, now, prosaically, a parking area and pedestrian zone leading to a supermarket and shopping arcade. Iron chains were fastened to the top of the stake, and a noose of rope passed through it at

neck height. Kindling and faggots were piled up in a pyramid around the stake. Dufief and the commissioners were present to witness the event. Tyndale was brought from the castle, with a small retinue of guards and friars. After refusing a final opportunity to recant, he was securely bound to the stake, by his feet, and by the iron chains around his calves and chest. The noose was placed round his neck. He had then a brief period in which to pray. Foxe says that he cried, with fervent zeal and loud voice: ‘Lord, open the king of England’s eyes.’ The executioner, standing immediately behind the stake, tightened the noose at Dufief ’s signal. It had not been shown that Tyndale was a relapsed heretic, and he qualified for the mercy of being strangled in the moments before the fire was lit.

It appears that the executioner bungled his work, however, and that Tyndale was still alive as the flames engulfed him. ‘They speak much of the patient sufferance of Master Tyndale at the time of his execution,’ Hutton later wrote to Cromwell.

The executioner added fuel to the fire until the body was utterly consumed. The ashes were then disposed of, probably by throwing them into the sullen waters of the River Zenne, so that no trace of the heretic remained to defile the earth.

But Tyndale’s traces are everywhere, of course. ‘That old tongue, with its clang and its flavour,’ as the critic Edmund Wilson wrote of the Bible, ‘that we have been living with all our lives’, is Tyndale’s tongue. Its cadence, its rolling and happy phrases, its consolations and the elegance of its solace, are his.

Eight years before, he had anticipated his death. ‘There is none other way into the kingdom of life than through persecution and suffering of pain,’ he wrote, ‘and of very death after the ensample of Christ.’ In this belief, at least, and in the firmness of their faith, he and More are at one.

He did not write his own epitaph. A passage he left from I Corinthians serves as well: ‘And though I gave my body even that

I burned, and yet had no love, it profiteth me nothing.’ That he used love and not charity was technical evidence of his heresy, of course, and a prime reason why More wanted him burnt. But Tyndale did not die for charity; he died for love, for the love of God’s words and of their readers, and the most familiar work in the English language is thereby given the added grace of being a labour of love.

B

ack among the living, we catch several later glimpses of Harry Phillips. He fled from Paris to escape further English accusations. He was back in Louvain in 1537, where he tried to charm his way into the entourage of Reginald Pole. Pole was a former favourite of Henry VIII, who became passionately opposed to the divorce and the royal supremacy. He left England for Italy in 1532. The pope created him a cardinal and sent him as papal legate to the Low Countries. Henry declared Pole a traitor, and set a price on his head. In England, Pole’s brother and mother were beheaded.

Phillips had long since squandered his Tyndale pieces of silver. He may have intended to betray Pole for the reward money. Certainly, this is what Pole and his entourage feared.

John Hutton, the English agent in Brussels, was instructed by Cromwell to have Pole seized as a traitor in Liège in May 1537. Hutton wrote to Cromwell on 26 May to explain that the Regent, Margaret, had refused to arrest Pole on the grounds that ‘in all treaties the Pope’s legate was exempt’. Hutton added, however, that a renegade named Vaughan – not Stephen, but another of the same name who had ‘fled from England for manslaughter’ – had

revealed to him that he had ‘applied to Henry Phillippis, an Englishman in Louvayn, who offered to get him in to service with Card. Pole, knowing one of his gentlemen named Thrognorton.’ Vaughan told Hutton that Phillips was soon to sail for Cornwall with Throckmorton, carrying letters to Cardinal Pole’s friends as well as to Phillips’s father, ‘baked within a loaf of bread’. ‘I advised him to encourage the enterprise,’ Hutton wrote to Cromwell, ‘and gave him forty shillings.’

It was, of course, the last that Hutton saw of his money. Phillips was not found landing in Cornwall. But he did write a series of begging letters to his family that have survived. God knows the anxiety and poverty he had suffered, he said, and what ‘jeopardy’ he was now in. Unless he was helped, he said, he ‘must go to the wars or be a serving man’. He pleaded with his father for cash and reconciliation. ‘I call upon you for succour your miserable child Henry Phyllypps,’ he wrote. ‘I desire your blessing and help

contra calumniam

, which has followed me through Flanders, Allmaygne, Italy, and France. I have offended you, but never my country as my adversaries

falso asserunt

. I desire that the error of my youth may not destroy the hope of your goodness.’

Another screed was sent to Dr Brerewood, the chancellor of Exeter, who had taught him and whom he flattered as ‘my Maecenas’. He asked for help in his ‘extreme necessity’. He has been falsely vilified, he wrote, and ‘cannot bear to be deprived of both country and literature at the same time’. He asked if he might become a servant of anyone whom Brerewood had educated in the arts. He wrote to his brother Thomas, saying that he acknowledged that he had ‘dyvasted’ his claim on the family fortune, but that ‘I desire to purchase grace for other three years’ study’. He said that he was now but ten days’ journey from Thomas. ‘Only they who gave the bearer these letters know where I am,’ he ended. ‘Whoever is sent must be instructed by this bearer, where he got these.’

When this failed, he wrote to his brother William, this time giving an address: ‘it is in your hand to save or spill me … you may be here within 10 days … it is in Brabant, at Lovayn, in the house of Lambert Croolys, who knows always where I am’.

He realised that he was vulnerable himself – Hutton was looking for him – and fled from Louvain. He was back in the town in January 1538, sending further begging letters to Chancellor Brerewood in Exeter.

On 1 October 1538, Cromwell had further news of Phillips and ‘Michael Frognorton’ from his godson Thomas Tebold at Padua in Italy. It appeared that Throckmorton had indeed been in England. Tebold reported that Throckmorton was ‘merrily disposed and boasted how he had deceived Cromwell’ when he had taken Cardinal Pole’s messages to England, saying that ‘but for his crafty and subtle conveyance, Cromwell could have beheaded him’.

It was soon clear that Throckmorton was far from being a friend of Phillips, as Hutton had suggested. The next time he met Tebold, Throckmorton was ‘clothed in a coat of wolf skins and a cap of mail, as pale as ashes, blowing and puffing like unto a raging lion’. He said he had not slept all night. The reason was that ‘one Harry Philleps, sometime student in Lovayn, where he betrayed good Tyndall, had come out of Flanders, either driven by poverty to ask help of Pole, or because of evil behaviour.’ Phillips had been serving with the imperial army to keep body and soul together. He was ‘arrayed like a Svycer’, a Schweizer, a Swiss mercenary; he was ‘a ruffling man of war, with a pair of Almain boots’. He had arrived on foot, but Pole’s entourage, ‘thinking they perceived he had worn spurs, and for other suspicions, concluded he had been sent by Cromwell to destroy Pole or be a spy on him’.