Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (8 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

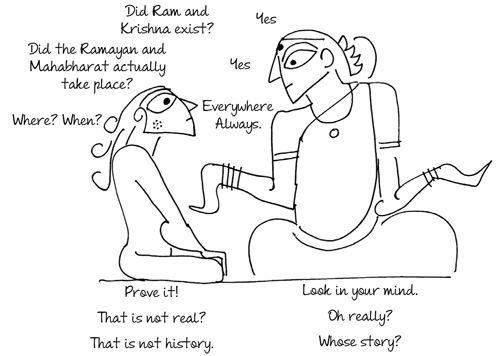

"Who is better," the West will ask, "the rule-following Ram or the rule-breaking Krishna?"

The Indian will answer, "Both are Vishnu."

"Who is better, the hermit Shiva, or the householder Vishnu?" the Chinese will ask.

The Indian will answer, "Both are God."

"So you don't have one God?"

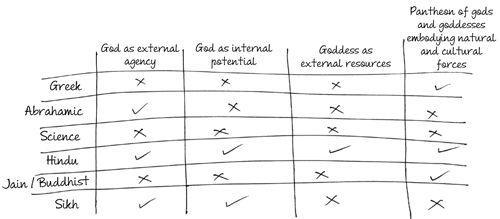

To this the Indian will respond, "We have one God. We also have many gods, who are manifestations of that same one God. But our God is distinct from Goddess. Depending on the context, God can be an external agency, a historical figure, or even inner human potential awaiting realization. What God do you refer to?"

Such answers will naturally exasperate the goal-focused Western mind and the order-seeking Chinese mind. They seek clarity. Indians are comfortable with ambiguity and contextual thinking, which manifests most visibly in the bobbing Indian headshake.

Steve wanted to enter into a joint venture with an Indian company. So Rahul decided to take him out to lunch. They went to a very famous hotel in New York, which served a four-course meal: soup, salad, the main course, followed by dessert. There was cutlery on the table, such as spoons, forks, knives, to eat each dish. In the evening, Rahul took him to an Indian restaurant where a thali was served. All items were served simultaneously, the sweet, the sour, the rice, the roti, the crispy papad, the spicy pickles. Everyone had to eat by hand, though spoons were provided for those who were embarrassed to do so or not too adventurous. Rahul then told Steve, "Lunch is like the West, organized and controlled by the chef. Dinner is like India, totally customized by the customer. You can mix and match and eat whatever you wish in any order you like. The joint venture will be a union of two very different cultures. They will never be equal. They will always be unique. Are you ready for it? Or do you want to wait till one changes his beliefs and customs for the benefit of the other?"

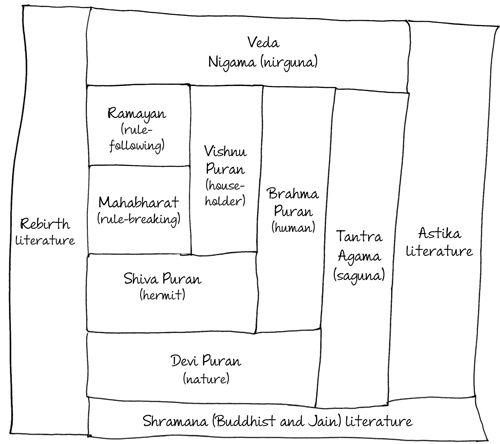

Not surprisingly, there is not one single clearly defined holy book in India. The Ramayan of the rule-following Ram complements the Mahabharat of the rule-breaking Krishna, both of which are subsets of the Vishnu Puran that tells the story of Vishnu. The Vishnu Puran speaks of the householder's way of life, and complements the Shiva Puran, which speaks of the hermit's way of life. Both make sense under the larger umbrella of the Brahma Puran, which speaks of human desire and dissatisfaction with nature that is described as the Goddess in the complementary text, the Devi Puran. All these fall in the category of Agama or Tantra where thoughts are personified as characters and made 'saguna'. These complement Nigama or Veda where thoughts remain abstract, hence stay 'nirguna'.

Vedic texts came to be known as astika because they expressed themselves using theistic vocabulary. But many chose to explain similar ideas without using theistic vocabulary. These were the nastikas, also known as shramanas, or the strivers, who believed more in austerity, meditation, contemplation and experience rather than transmitted rituals and prayers favoured by priests known as brahmins. The astikas and nastikas differed on the idea of God, but agreed on the idea of rebirth and karma, which forms the cornerstone of mythologies of Indian origin.

Over two thousand years ago, the nastikas distanced themselves from the ritualistic brahmins as well as their language, Sanskrit, and chose the language of the masses, Prakrit. They did not speak so much about God as they did about a state of mind: kaivalya, when all thoughts are realized, or nirvana when all forms dissolve. The one to achieve this state was Jina or tirthankar according to the Jains, and Buddha according to the Buddhists. The shramanas also believed that there have always existed Jinas and Buddhas in the cosmos.

The astikas came to be known as Hindus. For centuries, the word Hindu was used to indicate all those who lived in the Indian subcontinent. The British made it a category for administrative convenience to distinguish people who were residents of India but not Muslims. Later, Hindus were further distinguished from Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs. Thus, Hinduism, an umbrella term for all astika faiths, became a religion, fitting neatly into the Western template.

Sikhism emerged over the past 500 years in Punjab, as a result of two major forces: the arrival of Islam that came down heavily against idolatry, and the bhakti movement that approached divinity through emotion, not rituals. Like Hinduism it is theistic but it prefers the formless to the form.

These religions that value rebirth can be seen as fruits of the same tree or different trees in the same forest. All of them value thought over things, the timeless over the time-bound, the infinite over the finite, the limitless over the limited. They differentiate between truth that is bound by space, time and imagination (maya) from truth that has no such fetters (satya). They can be grouped under a single umbrella called 'sanatan'. Right-wing fundamentalists tend to appropriate this word more out of chauvinism than curiosity.

Sanatan means timeless. It refers to wisdom that has no founder and is best described as open-source freeware. Every idea is accepted but only that which survives the test of time, space and situation eventually matters. Unfettered by history and geography, sanatan is like a flowing river with many tributaries. At different times, at different places, different teachers have presented different aspects of sanatan in different ways, using different words, resulting in many overlaps yet many distinguishing features.

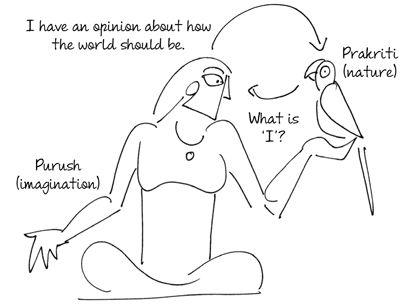

- Sanatan is rooted in the belief that nothing is permanent, not even death. What exists will wither away and what has withered away will always come back. This is the nature of nature. This is prakriti, which is visualized as the Goddess (feminine gender). The law of karma, according to which every event has a cause and consequence, governs prakriti.

- The human mind observes nature, yearns for permanence, and seeks to appreciate its own position in the grand scheme of things. The human mind can do this because it can imagine and separate itself from the rest of nature, as a purush. As man realizes the potential of a purush, he walks on the path of his dharma.

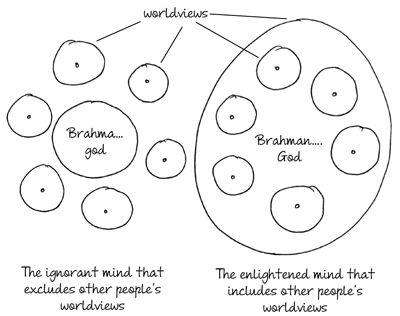

This is the Indian differentiator: the value given to imagination, to the human mind, to subjectivity. While truth in the West exists outside human imagination, in India, it exists within the imagination. In the West, imagination makes us irrational. In India, imagination reveals our potential, makes us both kind and cruel.

In sanatan, fear of death separates the animate (sajiva) from the inanimate (nirjiva). The animate respond to death in different ways: plants grow, animals run, while humans imagine and create subjective realities.

Of all living creatures, humans are special as they alone have the ability to outgrow the fear of death and change, and thus experience immortality. He who does so is God or bhagavan, worthy of worship. Those who have yet to achieve this state are gods or devatas.

Since every human is potentially God—hence god—every subjective truth is valid. Respect for all subjective realities gave rise to the doctrine of doubt (syad-vada) and pluralism (anekanta-vada) in Jainism, the doctrine of nothingness (shunya-vaad) in Buddhism and the doctrines of monism (advaita-vaad) as well as dualism (dvaita-vaad) in Hinduism.