Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (10 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

When India secured political freedom, the founding fathers of the nation state, mostly educated in Europe, shied away from all things religious and mythological as the partition of India on religious grounds had made these volatile issues. The pursuit of secular, scientific and vocational goals meant that all things sanatan were sidelined.

Most understanding of Indian thought today is derived from the works of nineteenth century European Orientalists, twentieth century American academicians, and the writings of Indians that tend to be reactionary, defensive and apologetic. In other words, Indianness today is understood within the Western template, with the Western lens and the Western gaze. These are so widespread that conclusions that emerge from them are assumed to be correct, as no one knows any better. Thus India, especially Hinduism, finds itself increasingly force-fitted into a Western religious framework complete with a definitive holy book (Bhagavad Gita), a trinity (Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva), a set of commandments (Manu Smriti), its own Latin (Sanskrit), a Protestant revolution (Buddhism versus Hinduism), a heretical tradition (Tantra), a class struggle (caste hierarchy), a race theory (Aryans and Dravidians), a forgotten pre-history (the Indus valley cities), a disputed Jerusalem-like geography (Ayodhya), a authoritarian clergy who need to be overthrown (brahmins), a pagan side that needs to be outgrown (worship of trees) and even a goal that needs to be pursued (liberation from materialism). Any attempt to join the dots differently, and reveal a different pattern is met with fierce resistance and is dismissed as cultural chauvinism. This academic tsunami is only now withdrawing.

Words such as 'gaze', 'construct', 'code' and 'design' that are more suited to explaining the Indian way entered the English language only after the 1970s with the rise of postmodern studies and the works of Foucault, Derrida, Barthes and Berger. These were not available to early writers who sought to express Indian thoughts in Indian terms, like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Vivekananda, Jyotibha Phule, Rabindranath Tagore, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, C. Rajagopalachari and Iravati Karve. Only in recent times have a few Indian scholars started taking up the challenge to re-evaluate ancient Indian ideas on Indian terms.

Indian universities dare not touch mythology for fear of angering traditionalists and fundamentalists who still suffer from the colonial hangover of seeking literal, rational, historical and scientific interpretations for sacred stories, symbols and rituals. Western universities continue to approach Indian mythology with extreme Western prejudice, without any empathy for its followers, angering many Indians, especially Hindus. As a result of this, an entire generation of Indians has been alienated from its vast mythic inheritance.

Caution!

There is vast difference between what we claim to believe in and what we actually believe in. Often, we are not even aware of what we actually believe in, which is why there is a huge gap between what we say and what we actually do.

- A corporation may believe that it is taking people towards the Promised Land, when, in fact, it may actually be compelling people to build its own pyramid.

- An entrepreneur may believe he is making his way to Elysium, when, in fact, he is one of the Olympian gods casting the rest into the monotony of Tartarus.

- Every 'jugadu' following the Indian way may believe that he is Ram or Krishna, creating ranga-bhoomi to attract Lakshmi, when, in fact, he may be the very opposite, Ravan and Duryodhan, establishing ranabhoomi to capture Lakshmi.

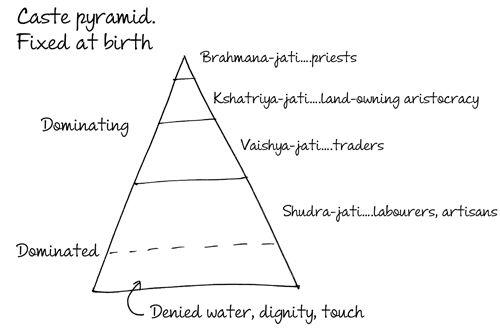

A hospitable home in India prides itself on providing every visitor to the house at least a glass of water on arrival; yet it is in this very same India that large portions of the population have been denied water from the village well, a dehumanizing act that costs India its moral standing. No discussion of India can be complete without referring to the plight of the dalits, a term meaning downtrodden that was chosen by the members of communities who face caste discrimination.

It is another matter that the problem of caste is used by the West to make Indians constantly defensive. Every time someone tries to say anything good about India, they are shouted down by pointing to this social injustice. With a typical Western sense of urgency, one expects a problem that established itself over the millennia to be solved in a single lifetime.

Caste is not so much a religious directive as it is an unwritten social practice, seen in non-Hindu communities of India as well, amplified by a scarcity of resources. So the attempt to wipe it out by standard Western prescriptions, such as changing laws and demanding behavioral modification, is not as effective as one would like it to be. A systemic, rather than cosmetic, change demands a greater line of sight, more empathy rather than judgment, something that seems rather counter-intuitive for the impatient social reformer.

The colloquial word for caste in India is jati; it traditionally referred to the family profession that one was obliged to follow. Jobs were classified as higher and lower depending on the level of ritual pollution. The priest and the teacher rose to the top of the pyramid while sweepers, undertakers, butchers, cobblers, were pushed to the bottom, often even denied the dignity of touch. In between the purest and the lowest were the landed gentry and the traders.

A person's jati was his identity and his support system, beyond the family. It determined social station. Whether a person belonged to a higher or lower jati, he avoided eating with, or marrying, members of other jatis. This institutionalized the jati system very organically over centuries. When members of one jati became economically more prosperous or politically more powerful, they did not seek to break the caste system; they sought to rise up the social ladder by emulating the behaviour of the more dominant caste of the village, which was not always the priest but often the landed gentry. This peculiar behaviour was termed Sanskritization by sociologists. Thus, the jati system was not as rigid as one is given to believe. At the same time it was not as open to individual choice as one would have liked it to be.

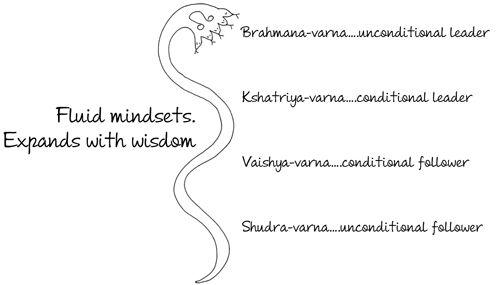

In the Mahabharat, the sage Markandeya tells the Pandavs the story of a butcher who reveals to a hermit that what matters is not what we do but why we do what we do. In other words, varna matters more than jati.

Varna, a word found even in the Vedic Samhitas, the earliest of Hindu scriptures, means 'colour'. Orientalists of the nineteenth century, predictably, took it literally and saw the varna-based division of society in racial terms. Symbolically, it refers to the 'colour of thought', or mindset, a meaning that is promptly dismissed as defensive.

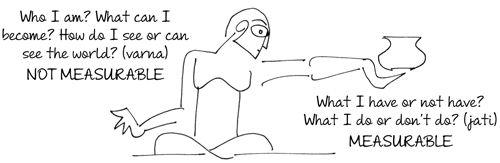

The sages of India did not value jati as much as they valued varna. Jati is tangible or saguna, a product of human customs. Varna is intangible, or nirguna, a product of the human imagination. Jati is fixed by virtue of birth but varna can flow and rise, or fall. A mind that expands in wisdom will see jati in functional terms, while a mind that is contracted in fear will turn jati into a tool for domination and exploitation.

Once, a teacher gave a great discourse on the value of thoughts over things. As he was leaving, a chandala blocked his path. A chandala is the keeper of the crematorium, hence belongs to the shudra jati. The teacher and his students tried to shoo him away. "What do you want me to move?" chuckled the chandala, "My mind has wandered away long ago, but my body is still here." The teacher had no reply. The chandala had truly understood what the teacher only preached. The chandala clearly belonged to the brahmana varna. But because he belonged to the shudra jati, he was shunned by society. Society chose to revere the teacher instead, valuing his caste, more than his mind. Observing this, the teacher realized society was heading for collapse, for when the mind values the fixed over the flexible, it cannot adapt, change or grow.

In medieval times, many brahmins wrote several dharma-shastras giving their views on how society should be organized. One of the dharma-shastras known as Atreya Smriti stated that every child is born in the shudra-varna and can rise to the brahman-varna through learning. Another dharma-shastra known as Manu Smriti, however, saw varna and jati as synonyms, assuming that people of a particular profession have, or should have, a particular mindset. Atri was proposing the path of wisdom while Manu was proposing the path of domination.