Candide (9 page)

Authors: Voltaire

XIV

How Candide and Cacambo were received by the Jesuits in Paraguay

C

andide had brought with him from Cadiz such a footman as one often meets with on the coast of Spain and in the Colonies. He was one-quarter Spanish, the son of a half-breed and was born in Tucuman.

ar

He had been a singing boy, sexton, sailor, monk, pedlar, soldier, and lackey. His name was Cacambo. He had a great affection for his master, because his master was a very good man. He immediately saddled the two Andalusian horses. “Come, my good master, let’s follow the old woman’s advice, and hurry to leave this place without a backward glance.” Candide burst into a flood of tears: “Oh, my dear Cunégonde, must I leave you just as the governor was going to marry us? Cunégonde, so long lost and found again, what will now become of you?” “Lord,” said Cacambo, “she must do as well as she can: women are never at a loss. God takes care of them, and so let’s get going.” “But where will you take me? Where can we go? What can we do without Cunégonde?” cried the disconsolate Candide. “By St James of Compostella,” said Cacambo “you were going to fight against the Jesuits of Paraguay; now let’s go and fight for them. I know the road perfectly well; I’ll take you to their kingdom; they will be delighted with a captain that understands the Bulgarian drill; you will certainly make a prodigious fortune. If we cannot find our account in one world, we’ll find it in another. It is a great pleasure to see new objects and perform new exploits.”

andide had brought with him from Cadiz such a footman as one often meets with on the coast of Spain and in the Colonies. He was one-quarter Spanish, the son of a half-breed and was born in Tucuman.

ar

He had been a singing boy, sexton, sailor, monk, pedlar, soldier, and lackey. His name was Cacambo. He had a great affection for his master, because his master was a very good man. He immediately saddled the two Andalusian horses. “Come, my good master, let’s follow the old woman’s advice, and hurry to leave this place without a backward glance.” Candide burst into a flood of tears: “Oh, my dear Cunégonde, must I leave you just as the governor was going to marry us? Cunégonde, so long lost and found again, what will now become of you?” “Lord,” said Cacambo, “she must do as well as she can: women are never at a loss. God takes care of them, and so let’s get going.” “But where will you take me? Where can we go? What can we do without Cunégonde?” cried the disconsolate Candide. “By St James of Compostella,” said Cacambo “you were going to fight against the Jesuits of Paraguay; now let’s go and fight for them. I know the road perfectly well; I’ll take you to their kingdom; they will be delighted with a captain that understands the Bulgarian drill; you will certainly make a prodigious fortune. If we cannot find our account in one world, we’ll find it in another. It is a great pleasure to see new objects and perform new exploits.”

“Then you have been to Paraguay,” said Candide. “Indeed I have,” replied Cacambo. “I was a cook in the College of the Assumption,and I know the new government of Los Padres

as

as well as I know the streets of Cadiz. Oh, it is an admirable government, that is most certain! The kingdom is at present more than three hundred leagues in diameter, and divided into thirty provinces; Los Padres own everything there, and the people have no money at all. This you must allow is the masterpiece of justice and reason. For my part, I see nothing so divine as Los Padres, who wage war in this part of the world against the troops of Spain and Portugal, and at the same time they hear the confessions of those very princes in Europe who kill Spaniards in America, and in Madrid they send them to heaven. This pleases me exceedingly; but let us get going; you are going to see the happiest and most fortunate of all mortals. How charmed will Los Padres be to hear that a captain who understands the Bulgarian drill is coming.”

as

as well as I know the streets of Cadiz. Oh, it is an admirable government, that is most certain! The kingdom is at present more than three hundred leagues in diameter, and divided into thirty provinces; Los Padres own everything there, and the people have no money at all. This you must allow is the masterpiece of justice and reason. For my part, I see nothing so divine as Los Padres, who wage war in this part of the world against the troops of Spain and Portugal, and at the same time they hear the confessions of those very princes in Europe who kill Spaniards in America, and in Madrid they send them to heaven. This pleases me exceedingly; but let us get going; you are going to see the happiest and most fortunate of all mortals. How charmed will Los Padres be to hear that a captain who understands the Bulgarian drill is coming.”

As soon as they reached the first barrier, Cacambo called to the advance-guard, and told them that a captain wanted to speak to my lord the general. Notice was given to the main-guard, and immediately a Paraguayan officer ran to throw himself at the feet of the commandant, to impart this news to him. Candide and Cacambo were immediately disarmed, and their two Andalusian horses were seized. The two strangers were placed between two files of soldiers. The commandant was at the farther end with a three-cornered cap on his head, his gown tucked up, a sword by his side, and a half-pike in his hand. He made a sign, and instantly twenty-four soldiers surrounded the new-comers. A sergeant told them that they must wait, the commander could not speak to them; and that the reverend father provincial had forbidden any Spaniard to open his mouth except in his presence, or to stay longer than three hours in the province. “And where is the reverend father provincial?” said Cacambo. “He has just said mass, and is at the parade,” replied the sergeant, “and in about three hours time you may possibly have the honour of kissing his spurs.” “But,” said Cacambo, “the captain, who as well as myself is dying of hunger, is no Spaniard but a German; can’t we have some breakfast while waiting for his reverence?”

The sergeant immediately went off to report this speech to the commandant. “God be praised,” said the reverend commandant; “since he is a German I will hear what he has to say; bring him to my arbour.” They immediately led Candide to a beautiful pavilion adorned with a colonnade of green marble spotted with yellow, and with an inter-texture of vines, which served as a kind of cage for parrots, humming-birds, fly-birds, Guinea hens, and all other curious kinds of birds. An excellent breakfast was provided in vessels of gold, and while the Paraguayans were eating coarse Indian corn out of wooden dishes in the open air, and exposed to the burning heat of the sun, the reverend father commandant retired to his cool arbour.

He was a very handsome young man, round-faced, fair, and fresh-coloured, his eyebrows were finely arched, he had a piercing eye, the tips of his ears were red, his lips vermilion, and he had a bold and commanding air; but such a boldness as neither resembled that of a Spaniard nor of a Jesuit. Their confiscated weapons were returned to Candide and Cacambo, together with their two Andalusian horses. Cacambo gave the poor beasts some oats to eat close by the arbour, keeping a strict eye on them all the while for fear of ambush.

Candide first kissed the hem of the commandant’s robe, then they sat down at the table. “It seems you are a German,” says the Jesuit to him in that language. “Yes, reverend father,” answered Candide. As they pronounced these words they looked at each other with great amazement, and with an emotion that neither could conceal. “Which part of Germany are you from?” said the Jesuit. “From the dirty province of Westphalia,” answered Candide. “I was born in the castle of Thunder-ten-tronckh.” “Oh heavens! is it possible?” said the commandant. “What a miracle!” cried Candide. “Can it be you?” said the commandant. At this they both fell back a few steps, then running into each other’s arms, embraced, and let fall a shower of tears. “Is it you, then, reverend father? You are the brother of the fair Miss Cunégonde? you that were slain by the Bulgarians! you the baron’s son! you a Jesuit in Paraguay! I must confess this is a strange world we live in. O Pangloss! Pangloss! what joy would this have given you if you had not been hanged.”

The commandant dismissed the negro slaves and the Paraguayans, who presented them with liquor in crystal goblets. He returned thanks to God and St Ignatius a thousand times; he clasped Candide in his arms, and both their faces were bathed in tears. “You will be more surprised, more affected, more beside yourself,” said Candide “when I tell you that Miss Cunégonde, your sister, whose body was supposed to have been ripped open, is in perfect health.” “Where?” “In your neighborhood, with the governor of Buenos Ayres; and I myself was going to fight against you.” Every word they uttered during this long conversation added some new matter of astonishment. Their souls fluttered on their tongues, listened in their ears and sparkled in their eyes. Like true Germans, they continued a long while at table, waiting for the reverend father, and the commandant spoke to his dear Candide as follows:

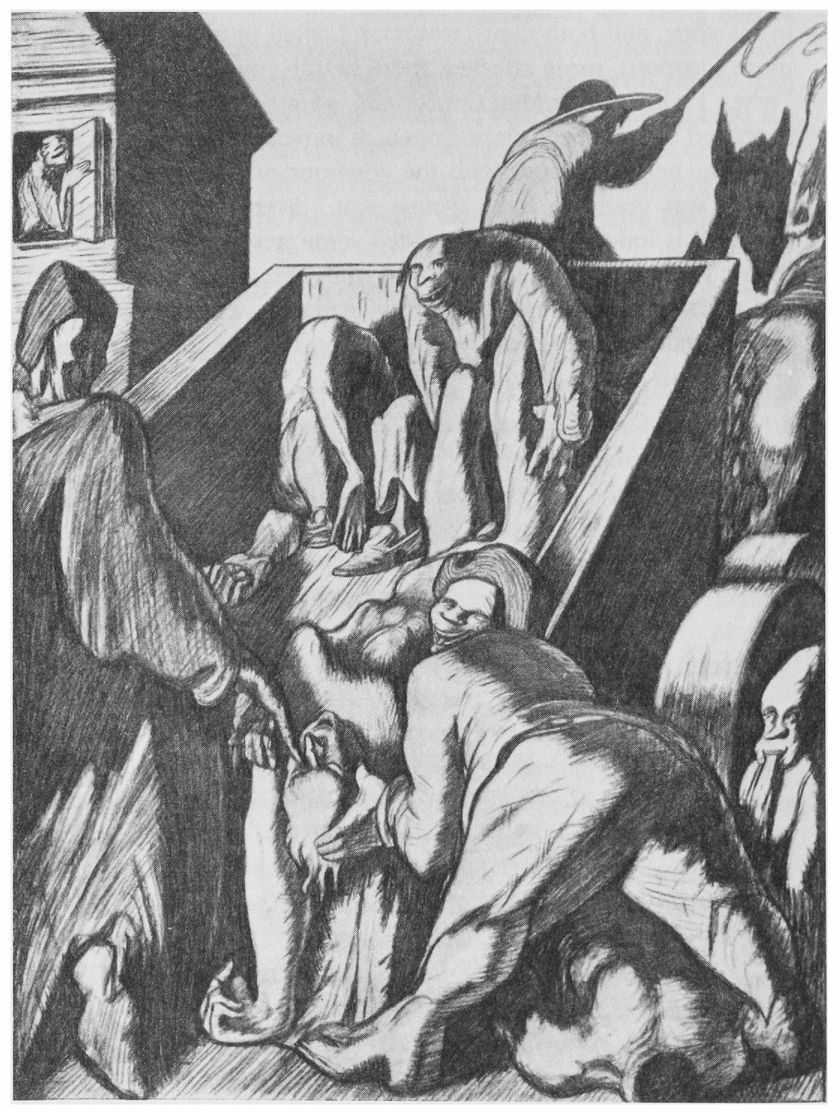

THE RESCUE OF THE BARON

XV

How Candide killed the Brother of his dear Cunégonde

“N

ever while I live shall I lose the remembrance of that horrible day on which I saw my father and brother barbarously butchered before my eyes, and my sister ravished. When the Bulgarians retired we searched in vain for my dear sister. She was nowhere to be found; but the bodies of my father, mother and myself, with two maid-servants and three little boys, all of whom had been murdered by the remorseless enemy, were thrown into a cart to be buried in a chapel belonging to the Jesuits, within two leagues of our ancestral castle. A Jesuit sprinkled us with some holy water, which was horribly salty, and a few drops of it went into my eyes. The father perceived that my eyelids stirred a little; he put his hand upon my breast, and felt my heart beat; I was rescued and at the end of three weeks I had perfectly recovered. You know, my dear Candide, I was very handsome. I became still more so, and the reverend father Croust,

at

superior of that house, took a great fancy to me. He gave me the habit of the order, and some years afterwards I was sent to Rome. Our general needed new recruitments of young German Jesuits. The sovereigns of Paraguay admit of as few Spanish Jesuits as possible; they prefer those of other nations, whom they believe to be more obedient to command. The reverend father-general judged me fit to work in that vineyard. I set out with a Pole and a Tyrolese. Upon my arrival I was honoured with a sub-deaconship and a lieutenancy. Now I am colonel and priest. We shall give a warm reception to the King of Spain’s troops; I can assure you they will be well excommunicated and beaten. Providence has sent you hither to assist us. But is it true that my dear sister Cunégonde is in the neighbourhood with the governor of Buenos Ayres?” Candide swore that nothing could be more true; and the tears began to trickle down their cheeks again.

ever while I live shall I lose the remembrance of that horrible day on which I saw my father and brother barbarously butchered before my eyes, and my sister ravished. When the Bulgarians retired we searched in vain for my dear sister. She was nowhere to be found; but the bodies of my father, mother and myself, with two maid-servants and three little boys, all of whom had been murdered by the remorseless enemy, were thrown into a cart to be buried in a chapel belonging to the Jesuits, within two leagues of our ancestral castle. A Jesuit sprinkled us with some holy water, which was horribly salty, and a few drops of it went into my eyes. The father perceived that my eyelids stirred a little; he put his hand upon my breast, and felt my heart beat; I was rescued and at the end of three weeks I had perfectly recovered. You know, my dear Candide, I was very handsome. I became still more so, and the reverend father Croust,

at

superior of that house, took a great fancy to me. He gave me the habit of the order, and some years afterwards I was sent to Rome. Our general needed new recruitments of young German Jesuits. The sovereigns of Paraguay admit of as few Spanish Jesuits as possible; they prefer those of other nations, whom they believe to be more obedient to command. The reverend father-general judged me fit to work in that vineyard. I set out with a Pole and a Tyrolese. Upon my arrival I was honoured with a sub-deaconship and a lieutenancy. Now I am colonel and priest. We shall give a warm reception to the King of Spain’s troops; I can assure you they will be well excommunicated and beaten. Providence has sent you hither to assist us. But is it true that my dear sister Cunégonde is in the neighbourhood with the governor of Buenos Ayres?” Candide swore that nothing could be more true; and the tears began to trickle down their cheeks again.

The baron knew no end of embracing Candide; he called him his brother, his deliverer. “Perhaps,” said he, “my dear Candide, we shall be fortunate enough to enter the town sword in hand, and recover my sister Cunégonde.” “Ah! that is all I desire,” replied Candide, “for I intended to marry her; and I hope I shall still be able to.” “Insolent fellow!” replied the baron. “You! you have the impudence to marry my sister, who bears seventy-two quarterings! Really I think you are very presumptuous to dare so much as to mention such an audacious design to me.” Candide, thunderstruck at the oddness of this speech, answered: “Reverend father, all the quarterings in the world are of no significance. I have rescued your sister from a Jew and an Inquisitor; she is under many obligations to me, and she wants to marry me. My master Pangloss always told me that all people are by nature equal. Therefore, I will certainly marry your sister.” “We will see about that, villain!” said the Jesuit baron of Thunder-ten-tronckh, and struck him across the face with the flat side of his sword. Candide in an instant drew his rapier, and plunged it up to the hilt in the Jesuit’s body; but in pulling it out, reeking hot, he burst into tears. “Good God,” cried he, “I have killed my old master, my friend, my brother-in-law. I am the best man in the world, and yet I have already killed three men; and of these three two were priests.”

Cacambo, who was standing sentry near the door of the arbour, instantly ran up. “We can do nothing,” said his master, “but sell our lives as dearly as possible. They will undoubtedly look into the arbour; we must die sword in hand.” Cacambo, who had seen many of these kind of adventures, was not discouraged. He stripped the baron of his Jesuit’s habit and put it upon Candide, then gave him the dead man’s three-cornered cap, and made him mount on horse-back. All this was done in the wink of an eye. “Gallop, master,” cried Cacambo; “everybody will take you for a Jesuit going to give orders, and we will have passed the frontiers before they can overtake us.” He flew as he spoke these words, crying out aloud in Spanish: “Make way! make way for the reverend father-colonel!”

XVI

What happened to our two Travellers with two Girls, two Monkeys, and the savages called Oreillons

au

au

C

andide and his valet had already passed the frontiers before it was known that the German Jesuit was dead. The wary Cacambo had taken care to fill his satchel with bread, chocolate, some ham, some fruit, and a few bottles of wine. They pushed their Andalusian horses forward into a strange country, where there were no roads. At length, a beautiful meadow, divided by several streams, opened to their view. Cacambo suggested to his master that they eat, and he promptly set the example. “How can you expect me to feast upon ham when I have killed the baron’s son, and am doomed never more to see the beautiful Cunégonde? How will it serve me to prolong a wretched life that might be spent far from her in remorse and despair? And then what will the journal of Trevoux

av

say about all this?”

andide and his valet had already passed the frontiers before it was known that the German Jesuit was dead. The wary Cacambo had taken care to fill his satchel with bread, chocolate, some ham, some fruit, and a few bottles of wine. They pushed their Andalusian horses forward into a strange country, where there were no roads. At length, a beautiful meadow, divided by several streams, opened to their view. Cacambo suggested to his master that they eat, and he promptly set the example. “How can you expect me to feast upon ham when I have killed the baron’s son, and am doomed never more to see the beautiful Cunégonde? How will it serve me to prolong a wretched life that might be spent far from her in remorse and despair? And then what will the journal of Trevoux

av

say about all this?”

While he was making these reflections he still continued eating. The sun was now at the point of setting when our two wanderers heard cries which seemed to be uttered by a female voice. They could not tell whether these were cries of grief or joy; however, they instantly started up, full of that inquietude and apprehension which a strange place naturally inspires. The cries came from two young women who were tripping stark naked along the meadow while two monkeys followed close at their heels, biting their backs. Candide was moved to pity; he had learned to shoot while he was among the Bulgarians, and he could hit a nut off a bush without touching a leaf. Accordingly he took up his double-barrel Spanish rifle, pulled the trigger, and killed the two monkeys. “God be praised, my dear Cacambo, I have rescued two poor creatures from a perilous situation. If I have committed a sin in killing an Inquisitor and a Jesuit, I made ample amends by saving the lives of these two distressed girls. Perhaps they are young ladies of rank, and this assistance I have been so happy to give them may gain us great advantages in this country.”

Other books

What You Desire (Anything for Love, Book 1) by Clee, Adele

Ready to Kill by Andrew Peterson

Amanda Scott by The Dauntless Miss Wingrave

Harbinger by Cyndi Friberg

The Maze: Three tales of the future by Tahmaseb, Charity

Once Upon A Wedding Night by Sophie Jordan

Taking Care of Mrs. Carroll by Paul Monette

The Stranger Master (Vol. 2 - Total Control) by Paz, Sofia

The Woman I Wanted to Be by Diane von Furstenberg

Vann's Victory by Sydney Presley