Carrier (1999) (40 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

As planned, the F/A-18E (single seat) and -F (two-seat trainer) are more than just -C/D models with minor improvements. They are in fact brand-new airframes, with less than 30% commonality with the older Hornets. The airframe itself has been enlarged to accommodate the internal fuel load that was lacking in the earlier F/A-18’s. With a fuel fraction of around .3 (as opposed to the .23 of the earlier Hornets), much of the range/endurance problems of the earlier birds should be resolved. The twin engines are new General Electric F414-GE-400’s, which will each now deliver 22,000 lb/9,979 kg of thrust in afterburner. There is also a new wing, with enough room for an extra weapons pylon inboard of the wing fold line on each side, which should help resolve some of the complaints about the Hornet’s weapons load. To ensure that the Super Hornet can land safely with a heavier fuel/weapons load than earlier F/A-18’s, the airframe structure and landing gear have also been strengthened. Since most of the-E/F’s weapons load is planned to be expensive PGMs, which must be brought back if not expended, this is essential.

The Super Hornet will also be the first USN aircraft to make use of radar and infrared signature-reduction technologies. Most of the work in this area can be seen in the modified engine inlets, which have been squared off to reduce their signature and coated with radar-absorbing material. This should greatly increase the survivability and penetration capabilities of the new bird.

Finally, the Super Hornet will be the first naval aircraft to carry a new generation of electronic-countermeasures gear including the ALE-50, a towed decoy system that is proving highly effective in tests against the newest threats in the arsenals of our potential enemies.

To back up the new airframe and engines, the avionics of the new Hornet will be among the best in the world. The radar will be the same APG- 73 fitted to the late-production models of the F/A-18C/D. An even newer radar, based on the same fixed-phased-array technology as the APG-77 on the USAF’s F-22A Raptor, is under development as well. To replace the sometimes troublesome Nighthawk pod, Hughes has recently been selected to develop a third-generation FLIR/targeting system for the Super Hornet, which will give it the best targeting resolution of any strike aircraft in the world.

The cockpit, designed again by the incomparable Eugene Adam and his team, will have a mix of “glass” MFDs (in full color!), and an improved user interface for the pilot. One part of this will be a helmet-mounted sighting system for use with the new AIM-9X version of the Sidewinder AAM. Other weapons will include the current array of iron ordnance and PGMs, as well as the new GBU-29/30/31/32 JDAMS, AGM-154 JSOW, and AGM-84E SLAM-ER cruise missile.

There will also be provisions for the Super Hornet to carry larger external drop tanks as well as the same “buddy” refueling store used by the S-3/ES-3 to tank other aircraft.

All this capability comes at a cost, though. At a maximum gross weight of some 66,000 lb/29,937 kg, the Super Hornet will weigh more than any other aircraft on a flight deck, including the F-14 Tomcat.

When McDonnell Douglas (now part of Boeing Military Aircraft) was given the contract to develop the Super Hornet, they set out to have a high level of commonality with the existing F/A-18 fleet. Early on in the design process, though, it became apparent that only a small percentage of the parts and systems could be carried over to the new bird. Despite this lack of true commonality, the Super Hornet was the only new tactical aircraft in the Navy pipeline, and so the Navy went forward with its development.

Today, the aircraft is well into its test program, with low-rate production approved by Congress.

61

At around $58 million a copy (when full production is reached), the Super Hornet will hardly be a bargain ( -C/-D-model Hornets cost about half that). On the other hand, when stacked next to the estimated $158-million-dollar-per-unit cost of the USAF’s new F-22A Raptor stealth fighter, the Super Hornet looks like quite a deal! Considering the current budget problems within the Department of Defense, there is a real possibility that one program or the other might be canceled. Since the Super Hornet is already in production (the F-22A has just begun flight tests), it may have an edge in the funding battles ahead.

61

At around $58 million a copy (when full production is reached), the Super Hornet will hardly be a bargain ( -C/-D-model Hornets cost about half that). On the other hand, when stacked next to the estimated $158-million-dollar-per-unit cost of the USAF’s new F-22A Raptor stealth fighter, the Super Hornet looks like quite a deal! Considering the current budget problems within the Department of Defense, there is a real possibility that one program or the other might be canceled. Since the Super Hornet is already in production (the F-22A has just begun flight tests), it may have an edge in the funding battles ahead.

If the Super Hornet survives the budget wars, current plans have the Navy buying at least five hundred of them in the next decade. This means they will begin to replace early model F-14As when the first fleet squadron stands up and goes to sea in 2001. Meanwhile, there is advanced work on several Super Hornet derivatives, including a two-seat all-weather strike version (that would restore the lost capabilities of the A-6 Intruder) and an electronic combat version of the F/A-18F (the so-called “Electric Hornet”) that would replace the EA-6B Prowler.

The Future: Joint Strike Fighter (JSF)Airmen and other warfighters often get testy when they hear somebody trying to sell them a “joint” project. All too often, “joint” has meant, “Let’s pretend to cooperate, so the damned bean-counters and politicians won’t slash our pet projects again.” One of the longest-running of these joint dreams has looked to find a common airframe that

all

the services could use to satisfy their tactical fighter and strike requirements. The newest incarnation of this dream is called the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF). The lure of potential multi-billion-dollar savings from such a program is the basis for the JSF program, which is an attempt to reverse the historic trend of escalating unit cost for combat aircraft. Taxpayer “sticker shock” at the price of aircraft like the F-22 Raptor and F/A-18E/F Super Hornet is threatening to unleash a political backlash against the entire military aerospace complex. Thus the JSF program is aiming for a flyaway cost in the $30-to-$40-million range, for the first time emphasizing affordability rather than maximum performance.

all

the services could use to satisfy their tactical fighter and strike requirements. The newest incarnation of this dream is called the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF). The lure of potential multi-billion-dollar savings from such a program is the basis for the JSF program, which is an attempt to reverse the historic trend of escalating unit cost for combat aircraft. Taxpayer “sticker shock” at the price of aircraft like the F-22 Raptor and F/A-18E/F Super Hornet is threatening to unleash a political backlash against the entire military aerospace complex. Thus the JSF program is aiming for a flyaway cost in the $30-to-$40-million range, for the first time emphasizing affordability rather than maximum performance.

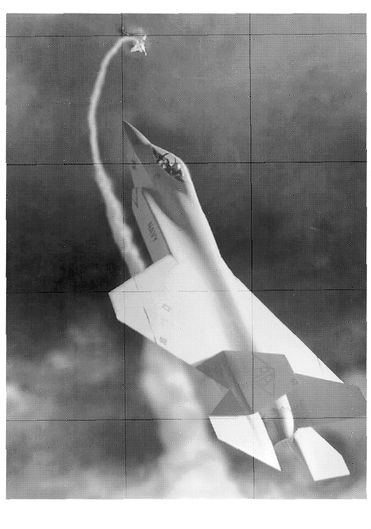

An artist’s concept of the Lockheed Martin Navy variant of the proposed Joint Strike Fighter (JSF).

LOCKHEED MARTIN, FORT WORTH

The contracting battle for JSF will pit Lockheed Martin against Boeing (newly merged with McDonnell Douglas), with the winner possibly becoming the builder of the last manned tactical aircraft of all time. With a planned buy of some two thousand aircraft, it certainly will be the most expensive combat aircraft program in history. Meanwhile, for this program to succeed, it will have to satisfy four demanding customers—the USAF, the USN, the USMC, and the British Royal Navy. To satisfy these customers, the JSF Program Office envisions a family of three closely related but not totally identical airframes.

The USAF sees JSF as a conventional, multi-role strike fighter to replace the F-16. With many foreign air forces planning to retire their F-16 fleets around 2020, there is a huge potential export market for such an aircraft. In addition, the Marine Corps needs some six hundred STOVL (Short Takeoff/ Vertical Landing) aircraft to replace both the F/A-18C/D Hornet and the AV-8B Harrier. The similar Royal Navy requirement is for just sixty STOVL aircraft to replace the FRS.2 Sea Harriers embarked on their small

Invincible-

class (R 05) aircraft carriers. In December of 1995, the United Kingdom signed a memorandum of understanding as a collaborative partner in developing the aircraft with the United States, and is contributing $200 million toward the program. The Royal Navy plans to replace the aging V/STOL Sea Harrier with a short-takeoff-and-vertical-landing version of the JSF.

Invincible-

class (R 05) aircraft carriers. In December of 1995, the United Kingdom signed a memorandum of understanding as a collaborative partner in developing the aircraft with the United States, and is contributing $200 million toward the program. The Royal Navy plans to replace the aging V/STOL Sea Harrier with a short-takeoff-and-vertical-landing version of the JSF.

The U.S. Navy’s requirement is for three hundred “highly survivable” (meaning “stealthy”), carrier-based strike fighters to replace early-model F/A-18’s and the last of the F-14 Tomcats. Its version of the aircraft will have a number of differences with the other variants. For instance, the landing gear will have a longer stroke and higher load capacity than the USAF and USMC versions. To help during low-speed approaches, the Navy version will have a larger wing and larger tail control surfaces than the other JSF variants. The larger wing also means increased range and payload capability for the Navy variant, with almost twice the range of an F-18C on internal fuel.

As you would expect, the internal structure of the Navy variant will be strengthened in order to handle the loads associated with catapult launches and arrested landings. There will be a carrier-suitable tailhook, though this may not have to be as strong as on previous naval aircraft, because the JSF will be powered by the same Pratt & Whitney F119-PW-100 turbofan planned for use on the USAF F-22A Raptor. This engine has a “2-Dimensional” nozzle (it will rotate in the vertical plane), which will allow it to have much lower landing approach speeds than current carrier aircraft, and may allow the next generation of carriers (CVX) to do away with catapults altogether.

The Navy’s need for survivability means that the JSF design will have a level of stealth technology comparable with the F-22 or B-2 stealth designs, which are the current gold standard in that area. All ordnance will be internally carried, and plans are for it to carry two 2,000-lb/909.1-kg-class weapons in addition to an internal gun and AAMs

Boeing and Lockheed Martin are scheduled to conduct a fly-off of their competing JSF designs in the year 2000, with a contract award the following year. The Boeing model is known as the X-32, while the Lockheed Martin design has been designated X-35. The winning entry should become operational sometime around 2010, at which time it will begin to replace the remaining F/A-18C/D aircraft in service. This is a make-or-break program for all the armed services of the United States. If it works, then the U.S. and our allies will have the pre-eminent strike fighter of the 21st century at their command.

The Future: Common Support AircraftWhile fighters and strike aircraft are important, the various support aircraft like the S-3 Viking and E-2 Hawkeye play equally vital roles in a CVW. And like fighters, they will someday have to be replaced. While this is not going to happen soon, planning for what will be known as the Common Support Aircraft (CSA) is already underway. This aircraft will take over the AEW, COD, ESM/SIGINT, and perhaps even tanker roles currently handled by no less than three different airframes. As always, funding is a problem. Right now, there is very little money available for the development of a new medium-lift airframe that could be made carrier-capable. In current-year dollars, it would probably cost something like $3 billion just to design and develop the airframe. And the price of the various mission equipment packages for each role is anybody’s guess.

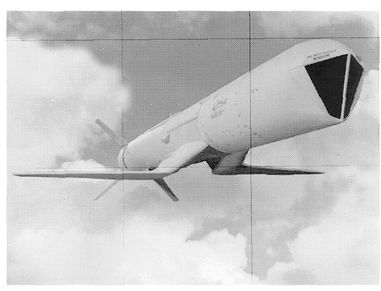

An artist’s concept of an AGM-84 SLAM-ER cruise missile. The SLAM-ER is headed into production, and will be the long-range strike weapon for naval aviation into the 21st century.

BOEING MISSILE SYSTEMS

One likely way around this dilemma might involve adapting for the Navy the new V-22 Osprey tilt-rotor transport currently entering production for the USMC and USAF. A V-22-based CSA could eliminate much of the airframe development costs and allow the design of state-of-the-art mission-equipment packages. It might even replace the SH-60Rs and CH-60’s when they begin to wear out.

The Future: Bombs and MissilesWith the introduction of GPS-guided air-to-ground ordnance and improved versions of a number of older PGM systems, the era of Navy aircraft dropping and firing unguided ordnance is dead.

62

In Operation Deliberate Force in Bosnia, for example, something like 70% of the weapons expended in that short but effective air campaign were PGMs. This percentage is likely to rise in future conflicts. What follows is a quick look at the programs that are important to naval aviators.

AGM-84E SLAM Expanded Response Missile62

In Operation Deliberate Force in Bosnia, for example, something like 70% of the weapons expended in that short but effective air campaign were PGMs. This percentage is likely to rise in future conflicts. What follows is a quick look at the programs that are important to naval aviators.

As mentioned earlier, the engineers at Boeing Missile Systems have been working on an improved version of the AGM-84E SLAM missile, which they call SLAM Expanded Response (SLAM-ER). SLAM-ER is designed to add a new generation of technology to the solid foundation laid by Harpoon and SLAM. This new missile will give the Navy a standoff strike weapon with unprecedented lethal power and accuracy. Improvements to the basic SLAM include a pair of “pop-out” wings (similar to those on the TLAM), which will give it more range (out to 150 nm/278 km) and better maneuverability. A new warhead utilizes the same kind of reactive titanium casing used on the Block III TLAM, while its nose has been modified with a new seeker window to give the seeker a better field-of-view. The guidance system of SLAM-ER incorporates a new software technology developed by Boeing and the labs at Naval Weapons Center at China Lake, California. Known as Automatic Target Acquisition (ATA, also known as Direct Attack Munition Affordable Seeker—DAMASK), it allows the SLAM-ER seeker to automatically pick out a target from the background clutter. The seeker then “locks” it up and flies the missile to a precise hit (within three meters/ten feet of the planned aimpoint). The SLAM-ER is already in low-rate production and has passed all of its tests with flying colors. In fact, this program has become so successful that the Navy has deleted its funding for the planned Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSAM), since SLAM-ER completely meets the requirements for that. Current plans have SLAM-ER entering the fleet in 1999.

Other books

An Apple a Day Keeps the Dragon Away by Amber D Sistla

Be My Baby by Fiona Harper

Entangled by Elliott, K

Warlock Unbound: Heart's Desire, Book 4 by Dana Marie Bell

Hell's Corner by David Baldacci

Cressida's Dilemma by Beverley Oakley

Testimonies: A Novel by O'Brian, Patrick

The Hidden Life by Erin Noelle