Carrier (1999) (37 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

On board, the crew of five is busy, for they’re doing a job that on the larger E-3 Sentry takes several dozen personnel. The pilot and copilot fly precisely positioned and timed racetrack-shaped patterns, designed to optimize the performance of the E-2C’s sensors. In back, the three radar-systems operators are tasked with tracking and sorting the contacts detected by the Hawkeye’s APS-145 radar. This Westinghouse-built system is optimized for operations over water and can detect both aircraft and surface contacts out to a range of up to 300 nm/345 mi/552 km. To off-load as much of the workload as possible, a great deal of the raw data is sent back to the task force’s ships via a digital data link. With this off-board support, the three console operators are able to control a number of duties, including intercepts, strike and tanker operations, air traffic control, search and rescue missions, and even surface surveillance and OTH targeting.

Along with the 141 E-2Cs produced for the USN, the Hawkeye has had considerable export success. No less than six foreign governments have bought them: Israel (four), Egypt (six), France (two for their new carrier

Charles de Gaulle),

Japan (thirteen), Singapore (four), and Taiwan (four). There are more Hawkeyes in use throughout the world than any other AEW aircraft ever built.

Charles de Gaulle),

Japan (thirteen), Singapore (four), and Taiwan (four). There are more Hawkeyes in use throughout the world than any other AEW aircraft ever built.

There also has been one major variant of the Hawkeye, a transport version known as the C-2A Greyhound. Basically an E-2 airframe with a broader fuselage and the radar rotodome deleted, it can deliver cargo and passengers hundreds of miles/kilometers out to sea. Known as a COD (for Carrier Onboard Delivery) aircraft, it replaced the elderly C-1 Trader, which is itself a variant of the earlier E-1 Tracker. With its broad rear loading ramp and fuselage, the C-2 can carry up to twenty-eight passengers, twenty stretcher cases, or cargo up to the size of an F-110 engine for the F-14.

The Hawkeye has had a long run in USN service. The original -A model was first flown in October 1960, to provide early warning services for the new generation of supercarriers then coming into service. In January 1964, the first of fifty-nine E-2As were delivered to their squadrons, and were shortly headed into combat in Southeast Asia. These were later updated to the E-2B standard, which remained in use until replaced by the E-2C in the 1970’s. The first E-2Cs entered USN service with Airborne Early Warning Squadron (VAW) 123 at NAS Norfolk, Virginia, in November of 1973. The -C-model Hawkeye was produced in order to provide the F-14 Tomcat with an AEW platform matched to the new fighter’s capabilities. Though visually identical to the earlier models, the E-2C was equipped with new-technology digital computers that provided a greatly increased capability for the new Hawkeye. These gave the operators the ability to track and intercept the dozens of Soviet bombers and hundreds of ASMs and SSMs that were expected to be fired at CVBGs if the Cold War ever turned “hot.”

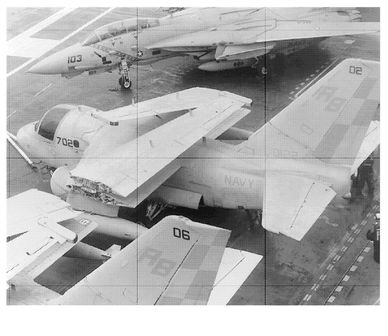

E-2C Hawkeye AEW aircraft on the deck of the USS

George Washington

(CVN-73). They generally parked alongside the island structure, on a spot called “the Hummer Hole.”

George Washington

(CVN-73). They generally parked alongside the island structure, on a spot called “the Hummer Hole.”

JOHN D. GRESHAM

In any event, the E-2Cs never directed the massive air battles they had been designed for. Instead, the Hawkeye crews spent the declining years of the Cold War flying their racetrack patterns over the fleets, maintaining their lonely vigil for a threat that never came. Carrier-based Hawkeyes were not strangers to combat, however. E-2Cs guided F-14 Tomcat fighters flying combat air patrols during the 1981 and 1989 air-to-air encounters with the Libyan Air Force, as well as the joint USN/USAF strike against terrorist-related Libyan targets in 1986. Israeli E-2Cs provided AEW support during their strikes into Lebanon in 1982, and again during the larger invasion the following year. More recently, E-2Cs provided the command and control for successful operations during the Persian Gulf War, directing both land strike and CAP missions over Iraq and providing control for the shoot-down of the two Iraqi F-7/MiG-21 fighters by carrier-based F/A-18’s. E-2 aircraft have also worked extremely effectively with U.S. law enforcement agencies in drug interdictions.

Today the entire Hawkeye fleet is being upgraded under what is called the Group II program. Along with thirty-six new-production aircraft, the entire USN E-2C fleet is being given the improved APS-145 radar, new computers, avionics, data links, and a GPS/INS system to improve flight path and targeting accuracy. This means that a single Hawkeye can now track up to two thousand targets at once in a volume of six million cubic miles of airspace and 150,000 square miles of territory. Current plans have the Hawkeye/ Greyhound fleet serving until at least the year 2020, when a new airframe known as the Common Support Aircraft (CSA) will be built in an AEW version. By that time, the basic E-2 airframe will have served for almost six decades!

A VS-32 S-3B Viking ASW aircraft on the deck of the USS George

Washington

(CVN-73) with wings folded. The S-3B has rapidly taken over many critical roles in carrier operations, espcially in-flight refueling of other aircraft.

Washington

(CVN-73) with wings folded. The S-3B has rapidly taken over many critical roles in carrier operations, espcially in-flight refueling of other aircraft.

JOHN D. GRESHAM

Antisubmarine warfare (ASW) is probably the most complex, frustrating, operationally challenging, and technically secretive mission that any aircraft can be called upon to perform. To locate, track, classify, and destroy a target as elusive as a nuclear submarine in the open ocean often seems virtually impossible. And against a quiet modern diesel boat in noisy coastal waters, the odds are even worse. In fact, the ASW mission doesn’t have to be that successful. It has succeeded as long as enemy subs are forced to go deep, run quiet, and keep their distance from a Naval task force or convoy. It is a matter of record that the most effective weapon against submarines during the Second World War was the ASW patrol aircraft. Such aircraft have continued to do this job ever since.

Today, the USN operates two fixed-wing ASW aircraft. One is the venerable four engined P-3C Orion, which operates from land bases. The other is its “little brother” from the Lockheed Martin stable, the S-3B Viking, which is carrier-capable. Airborne ASW has long been a Lockheed specialty. Their land-based Hudson and Ventura patrol bombers played a key role in World War II against German U-boats. More recently, their P-2V Neptune and P-3 Orions have kept vigil over the world’s oceans, watching for everything from submarines to drug-running speedboats. The so-called “sea control” mission is thankless work, with nearly day-long missions, most of which are flown over inhospitable and empty seas. The boredom arising from these missions in no way reduces their importance. A maritime nation that cannot monitor and control the sea-lanes it uses is destined to sail at the whims of other powers.

Early on, carrier aviators knew that they too needed the services of such aircraft, and began to build specially configured ASW/patrol aircraft shortly after the end of World War II. The first modern carrier-based ASW aircraft was Grumman’s twin-engine S-2 Tracker, which entered service in 1954 and remained in the fleet for over twenty-five years with more than six hundred built.

54

In 1967, the growing sophistication of the Soviet submarine threat led the Navy to launch a competition for a radically new generation of carrier ASW aircraft. Known as the VSX program, it was designed both to replace the Tracker and to provide a utility airframe for other applications. In 1969, the design submitted by Lockheed and Vought was declared the winner and designated S-3. The prototype S-3A first flew on January 21 st, 1971, and the type entered service in 1974 with VS-41 at NAS North Island, California. By the time S-3A production ended in 1978, 179 had been delivered.

54

In 1967, the growing sophistication of the Soviet submarine threat led the Navy to launch a competition for a radically new generation of carrier ASW aircraft. Known as the VSX program, it was designed both to replace the Tracker and to provide a utility airframe for other applications. In 1969, the design submitted by Lockheed and Vought was declared the winner and designated S-3. The prototype S-3A first flew on January 21 st, 1971, and the type entered service in 1974 with VS-41 at NAS North Island, California. By the time S-3A production ended in 1978, 179 had been delivered.

The S-3 Viking is a compact aircraft, with prominent engine pods for its twin TF-34-GE-2 engines. This is the same basic non-afterburning turbofan used on the Air Force’s A-10 “Warthog,” and its relatively quiet “vacuum-cleaner” sound gives the Viking its nickname: the “Hoover.” The crew of four sits on individual ejection seats, with the pilot and copilot in front, and the tactical coordinator (TACCO) and sensor operator (SENSO) in back. A retractable aerial refueling probe is fitted in the top of the fuselage, and all S-3B aircraft are capable of carrying an in-flight refueling “buddy” store. This allows the transfer of fuel from the Viking aircraft to other Naval aircraft. Because ASW is a time-consuming business that requires a lot of patience and equipment, the Viking is relatively slow, with a long range and loiter time. This means the S-3 is pretty much a “truck” for the array of sensors, computers, weapons, and other gear necessary to find and hunt submarines. But don’t think that the Viking is a sitting duck for anyone with a gun or AAM. The S-3 is surprisingly nimble, and it’s able to survive even in areas where AAW threats exist.

There are three primary ways to find a submarine that does not want to be found. You can listen for sounds, you can find it magnetically (something like the way compass needles find north), or you can locate a surfaced sub with radar. Since sound waves can travel a long way underwater, a sub’s most important “signature” is acoustic. But how can an aircraft noisily zooming through the sky listen for a submarine gliding beneath the waves? The answer, developed during World War II, is the sonobuoy. This is an expendable float with a battery-powered radio and a super-sensitive microphone. “Passive” sonobuoys simply listen. “Active” sonobuoys add a noise-makerthat sends out sound waves in hope of creating an echo. By dropping a pattern of sonobuoys and monitoring them, an ASW aircraft can spread a wide net to catch the faint sounds of the sub’s machinery, or even the terrifying “transient” of a torpedo or missile launch.

Another detectable submarine signature is magnetism. Since most submarines are made of steel, they create a tiny distortion of the earth’s magnetic field as they move.

55

The distortion is

very

small, but it is detectable. A “magnetic anomaly detector” (MAD) can sense this signature, but it is so weak that the aircraft must practically fly directly over the sub at low altitude to do so.

56

In order to isolate the MAD from the plane’s own electromagnetic field, it is mounted on the end of a long, retractable “stinger” at the tail of the aircraft.

55

The distortion is

very

small, but it is detectable. A “magnetic anomaly detector” (MAD) can sense this signature, but it is so weak that the aircraft must practically fly directly over the sub at low altitude to do so.

56

In order to isolate the MAD from the plane’s own electromagnetic field, it is mounted on the end of a long, retractable “stinger” at the tail of the aircraft.

Eventually, every submarine must come to periscope depth to communicate, snorkel, or just take a quick look around. Although periscope, snorkel, and communications masts are usually treated with radar-absorbing material, at close range sufficiently powerful and sensitive radar may obtain a fleeting detection. Finally, there are more conventional means of detection. For example, an airborne receiver and direction finder may pick up a sub’s radio signals, if it is foolish or unlucky enough to transmit when an enemy is listening. And sometimes the telltale “feather” from a mast can be seen visually or through an FLIR system.

The integrated ASW package of the initial version of the Viking, the S-3A, was designed to exploit all of these possible detection signatures. Sixty launch tubes for sonobuoys are located in the underside of the rear fuselage. In addition, the designers provided the ASQ-81 MAD system, an APS-116 surface search radar, a FLIR system, a passive ALR-47 ESM system to detect enemy radars, and the computer systems that tie all of these together. Once a submarine has been found, it is essential that all efforts be made to kill it. To this end, the S-3 was not designed to be just be a hunter; it was also a killer. An internal weapons bay can accommodate up to four Mk. 46 torpedoes or a variety of bombs, depth charges, and mines. Two wing pylons can also be fitted to carry additional weapons, rocket pods, flare launchers, auxiliary fuel tanks, or a refueling “buddy store.”

All this made the S-3A one of the best sub-hunting aircraft in the world, which was good enough in its first decade of service. By 1981, though, the -A model Viking clearly needed improvement in light of the growth in numbers and capabilities of the Soviet submarine fleet. In particular, the improved quieting of the Russian boats made hunting even more of a challenge. In order to improve the S-3’s avionics, sonobuoy, ESM and radar data processing, and weapons, a conversion program was started. The result was the S-3B, which upgraded basic -A model airframes to the new standard. The first S-3Bs began to arrive in the fleet in 1987, and they quickly showed both their new sea control abilities and capability to fire AGM-84 Harpoon antiship missiles. This is the version that serves today.

Other books

The Architect by Connell, Brendan

Canyon Secret by Patrick Lee

Hard Case Crime: Fake I.D. by Starr, Jason

'Tis the Season by Jennifer Gracen

The Book of Feasts & Seasons by John C. Wright

The Curious Quests of Brigadier Ffellowes by Sterling E. Lanier

Beauty in Breeches by Helen Dickson

Deceitfully (Sinfully Series) by Riley, Leighton

At My Door by Deb Fitzpatrick

His Reboot Girl (Emerald City #3) by Sofia Grey