Carrier (1999) (18 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

The new nuggets, meanwhile, are getting ready for their first overseas deployment. But before that happens, they are assigned a “call sign” (frequently “hung” on the new aviator during a squadron meeting). Call signs are nicknames used around the squadron to differentiate all the Toms, Dicks, Jacks, and Harrys that clutter up a ready room and make identification over a crowded radio circuit difficult. Most call signs get “hung” on a pilot because of some unique characteristic. Sometimes they are inevitable. Thus, every pilot named Rhodes is going to be named “Dusty,” just as any Davidson will be “Harley.” Others are more unique. One F-4 RIO (Radar Intercept Officer) who lost several fingers during an ejection over North Vietnam became “Fingers.” Another pilot became “Hoser” because of his tendency to rapidly fire 20mm cannon ammunition like water out of a fire hose. Most call signs last for life, and become a part of each naval aviator’s personality.

New pilots and NFOs normally arrive in a squadron during the first few months after it comes home from its last deployment. There they will be expected to get up to speed in the squadron’s aircraft, weapons, and other systems, as well as in the proper tactics for employing all of these. Thus by the time the squadron deploys, it is hoped the nuggets will be more dangerous to a potential enemy than to themselves or their squadron mates. To help them get started, new aviators are usually teamed with an older and more experienced member of the squadron. For example, in F-14 squadrons you normally see a nugget pilot teamed with a senior (second or third tour) RIO, who is probably a lieutenant commander. If the squadron flies single-seat aircraft like the F/A-18 Hornet, then the nugget pilot will be made the wingman to a more senior section leader. The final six months prior to the nugget’s first deployment are spent “working up” with the rest of the squadron, air wing, and carrier as they mold into a working team.

During the cruise, nuggets are expected to fly their share of missions in the flight rotation, stand watches as duty officers, and generally avoid killing themselves or anyone else without permission. If the nugget does these tasks well on his or her first overseas cruise (normally lasting six months), it is likely he or she has a future in the Naval aviation trade. It is further hoped that the rookie will have become proficient in flying all the various missions assigned to the squadron, and qualified to lead flights of the squadron’s aircraft. When the squadron returns from the cruise, the nuggets will (hopefully) have enough experience and enthusiasm to do it again the following year.

Most naval aviators have by this time been promoted to lieutenant (O-3), and have been entrusted with minor squadron jobs like public affairs, welfare, or morale duty. It is also the time that the Navy begins to notice those young officers who have promise. One sign you’ve been noticed is to be sent to school. If you are a good “stick” in an F-14 or F/A-18 squadron, for example, you may get a chance to head west to NAS Fallon near Reno, Nevada, to attend what the service calls the Naval Fighter Weapons School, which you probably know better as Topgun). Topgun is a deadly serious post-graduate-level school designed to create squadron-level experts on tactics and weapons employment. The E-2C community also has its own school co-resident at NAS Fallon, called Topdome, after the large rotating radar domes on their aircraft. Graduates of these schools have an automatic “leg up” on other aviators at their level, and will likely get choice assignments if they continue to shine. More than a few Topgun graduates have gone on to the Navy’s Test Pilot School at Patuxtents River, Maryland, or even to fly the Space Shuttle.

All too soon however, the second cruise arrives. Though second-cruise aviators are expected to show some leadership and help the new nugget air crews with their first cruises, most of what they do is fly. They fly a lot! Now is the time when taxpayers begin to get back the million-dollar-plus investments made in these young officers. Most naval aviators find life good at this stage. With a cruise of seniority over the nuggets, and none of the command responsibilities that will burden them later in their career, it is a nice time to be a naval aviation professional.

The Good Years—The Second and Third ToursThe Navy, wisely, is well aware that after two cruises, young naval aviators tend to be burned out and need shore duty to recharge their batteries. During this first shore tour (which lasts about three years), a young man or woman can earn a master’s degree (a necessity for higher promotion these days), start a family, and perhaps build a “real” home.

An officer who shows special promise for higher command may also be offered graduate work at one of the service universities (such as the Naval Post-Graduate School, the Naval War College, the National War College at Fort McNair, in Washington, D.C., or the Air University at Maxwell AFB, Alabama). Staff schools like these are designed to teach officers the skills needed for high-level jobs like running a squadron, planning for an air wing or battle group staff, or working for a regional commander in chief. There may also be an opportunity for the young officer to get some time as an IP at one of the FRSs. They might also serve in a staff job for an admiral or other major commander.

By the end of this three-year period, they will probably be ready to go back to a flying unit at sea. Our aviator is by now around thirty years old, with over eight years of service in the Navy, meaning that this flying tour represents a halfway point in his or her flying career. Here they will do some of their most demanding work. The second sea tour (of three to four years) puts the aviator out on a carrier for another two cruises—either as a member of a squadron, or perhaps as an officer on an air wing staff. Whatever the case, the aviator will get another heavy dose of flying, though this time there’ll be a great deal more responsibility. For it is during this time that officer enters the Navy equivalent of middle management. Specifically, this means that officers now have to provide more flight and strike leadership on missions, as well as expertise in the various planning cells that support flight operations.

Once this tour is completed, the aviator is almost guaranteed a two-year shore tour as an IP at either a training squadron or a FRS. There will also probably be a significant raise in pay, since promotion to lieutenant commander (O-4) normally occurs during this time. After the IP shore tour comes a department head tour, which is the start of their rise to command.

Command—The Top of the HeapFor naval aviators, the path to combat command starts when they arrive at their squadron for their third flying tour (another three-to-four-year, two-cruise sea tour) and are assigned a major squadron department (maintenance, training, operations, safety, supply, etc.) to run. How well they do here will ultimately determine how far they will go in the Navy. After the department head tour, officers who prove to be “only” average will go back to another shore tour, perhaps on a staff or to a project office at the Naval Air Systems Command, and will probably be allowed to serve their twenty years and retire. But if the Navy feels an officer has command potential, then things begin to happen quickly, starting with a two-year “joint” staff tour, which is designed to “round out” the officer’s career and provide the “vision” for working effectively with officers and personnel from other services and countries. Following this, the officer heads back to what will probably be his or her final flying tour, as the executive officer (XO) of a squadron. If the first cruise as XO goes well, the second cruise comes with a bonus—promotion to full commander (O-5) and the job of commanding officer (CO) of a squadron of naval aircraft.

It also is the beginning of the end of the officer’s squadron life. In less than eighteen months, our aviator will be handing over command of the unit to

his or her

XO, and the cycle moves on. From here on, aviators take one of two paths. They can take another staff tour, followed by “fleeting up” to take over their own air wing (with a promotion to captain, O-6). The other option is that they can take the path to command of an aircraft carrier. This includes nuclear power school, an O-6 promotion, and a two-year tour as a carrier XO. Following this comes a command tour of a “deep draft” ship (like a tanker, amphibious or logistics ship), and eventually command of their own carrier. Beyond that comes possible promotion to rear admiral and higher command. However, it is the “flying” years that make a naval aviator’s career worth the effort. Years later when they have retired or moved on to other pursuits, the aviators will likely look back and think about the “good years,” when they were young and free to burn holes in the sky, before heading back to the “boat.”

his or her

XO, and the cycle moves on. From here on, aviators take one of two paths. They can take another staff tour, followed by “fleeting up” to take over their own air wing (with a promotion to captain, O-6). The other option is that they can take the path to command of an aircraft carrier. This includes nuclear power school, an O-6 promotion, and a two-year tour as a carrier XO. Following this comes a command tour of a “deep draft” ship (like a tanker, amphibious or logistics ship), and eventually command of their own carrier. Beyond that comes possible promotion to rear admiral and higher command. However, it is the “flying” years that make a naval aviator’s career worth the effort. Years later when they have retired or moved on to other pursuits, the aviators will likely look back and think about the “good years,” when they were young and free to burn holes in the sky, before heading back to the “boat.”

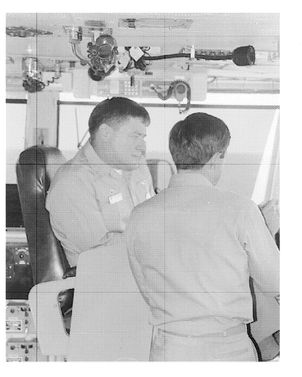

Captain Lindell “Yank” Rutheford, commanding officer of the aircraft carrier USS

George Washington

(CVN-73). Rutheford is a longtime F-14 Tomcat pilot who has risen to the top of his profession.

George Washington

(CVN-73). Rutheford is a longtime F-14 Tomcat pilot who has risen to the top of his profession.

JOHN D. GRESHAM

Building the Boats

O

fficially, the Navy calls it a “CV” or “CVN.” Sailors on the escorts call it a “bird farm.” Submariners wryly call it a target. But naval aviators call it—with something like reverence and religious awe—“the boat.” It is the central icon of

their

naval careers. In addition to being their home and air base, aircraft carriers hold an almost mystical place in the world of naval aviators. As we’ve already seen, young naval aviators’ skills (and future chances of promotion) are judged mainly on their ability to take off and land safely on “the boat.” Later, as they gain seniority, they’ll strive to command one of the giant supercarriers. Finally, at the sunset of their naval careers, they will be expected to lead the fight to obtain authorization and funding for construction of the new carriers that will serve several future generations of naval aviators.

fficially, the Navy calls it a “CV” or “CVN.” Sailors on the escorts call it a “bird farm.” Submariners wryly call it a target. But naval aviators call it—with something like reverence and religious awe—“the boat.” It is the central icon of

their

naval careers. In addition to being their home and air base, aircraft carriers hold an almost mystical place in the world of naval aviators. As we’ve already seen, young naval aviators’ skills (and future chances of promotion) are judged mainly on their ability to take off and land safely on “the boat.” Later, as they gain seniority, they’ll strive to command one of the giant supercarriers. Finally, at the sunset of their naval careers, they will be expected to lead the fight to obtain authorization and funding for construction of the new carriers that will serve several future generations of naval aviators.

Why this community obsession about “the boat”? The answers are both simple and complex. In the first chapter, I pointed out some of the reasons why sea-based aviation is a valuable national asset. However, for the Navy there is a practical, institutional answer aimed at preserving naval aviation as a community: “If you build it, they will come!” That is to say, as long as America is committed to building more aircraft carriers, the nation will also continue to design and build new aircraft and weapons to launch from them, and train air crews to man the planes. In other words, the operation of aircraft carriers and the building of new ones represent a commitment by the Navy and the nation to all of the other areas of naval aviation. New carriers mean that the profession has a future, and that young men and women have a rationale for making naval aviation a career. The continued designing and building of new carriers gives the brand-new “nugget” pilot or Naval Flight Officer (NFO), a star to steer for—a goal to justify a twenty-year career of danger, family separation, and sometimes thankless work.

This is fine, as far as it goes. And yet, as we head toward the end of a century in which aircraft carriers have been the dominant naval weapon, it is worth assessing their value for the century ahead. More than a few serious naval analysts have asked whether the kind of carriers being built today have a future, while everyone from Air Force generals to Navy submariners would like the funds spent on carrier construction to be reprogrammed for their pet weapons systems. Two hard facts remain. First, big-deck aircraft carriers are still the most flexible and efficient way to deploy sea-based airpower, and will remain so for the foreseeable future. Second, sea-based airpower gives national leaders unequaled options in a time of international crisis.

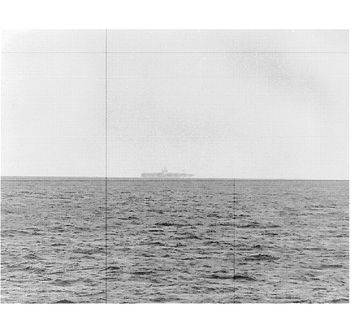

The USS

George Washington

in the Atlantic during JTFEX 97-3 in 1997. Once “worked up,” carrier groups are the “big sticks” of American foreign policy.

George Washington

in the Atlantic during JTFEX 97-3 in 1997. Once “worked up,” carrier groups are the “big sticks” of American foreign policy.

JOHN D. GRESHAM

With this in mind, let’s take a quick tour of the “boats” that America has been building for the past half century. In that way, you’ll get an idea not only of the design, development, and building of aircraft carriers, but also of the size, scope, and sophistication of the industrial effort all that takes.

Other books

Deception by Ken McClure

Sword Play by Linda Joy Singleton

Evidence of the Gods by Daniken, Erich von

Falling Idols by Brian Hodge

Sacrificed to the Demon (Beast Erotica) by Sims, Christie, Branwen, Alara

Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng

Birds Without Wings by Louis de Bernieres

The Blind Side by Michael Lewis

The Sky Is Falling by Caroline Adderson

What I'd Say to the Martians by Jack Handey