Carrier (1999) (20 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

By the late 1960’s the characteristics of what was initially known as SCB-102 (Ship Control Board Design 102) were firming up, with the following providing some idea of what the Navy desired:

•

Displacement—

Approximately 95,000 tons fully loaded.

Displacement—

Approximately 95,000 tons fully loaded.

•

Size—

A length of 1,092 feet/332.9 meters, beam of 134 feet/40.85 meters, a flight deck width of 250 feet/76.5 meters, and a maximum loaded draft of no more than 39 feet/11.9 meters.

Size—

A length of 1,092 feet/332.9 meters, beam of 134 feet/40.85 meters, a flight deck width of 250 feet/76.5 meters, and a maximum loaded draft of no more than 39 feet/11.9 meters.

•

Power Plant

—Two Westinghouse A4W nuclear reactors driving four General Electric steam turbines, turning four screws for a total of 280,000 shp. While the top speed is still classified, it is

well

over thirty-three knots.

Power Plant

—Two Westinghouse A4W nuclear reactors driving four General Electric steam turbines, turning four screws for a total of 280,000 shp. While the top speed is still classified, it is

well

over thirty-three knots.

•

Manning

—SCB-102 provided for a ship’s company of 2,900 enlisted personnel and 160 officers. Room was additionally provided for two thousand air wing personnel, thirty Marines, and seventy members of the flag staff. This added up to almost 5,200 embarked personnel.

Manning

—SCB-102 provided for a ship’s company of 2,900 enlisted personnel and 160 officers. Room was additionally provided for two thousand air wing personnel, thirty Marines, and seventy members of the flag staff. This added up to almost 5,200 embarked personnel.

•

Aircraft Complement

—Approximately ninety aircraft. These would include improved models of aircraft like the F-4 Phantom II, A-6 Intruder, A-7 Corsair II, and E-2 Hawkeye, as well as newer and larger planes like the F-14 Tomcat, S-3 Viking, and EA-6B Prowler.

Aircraft Complement

—Approximately ninety aircraft. These would include improved models of aircraft like the F-4 Phantom II, A-6 Intruder, A-7 Corsair II, and E-2 Hawkeye, as well as newer and larger planes like the F-14 Tomcat, S-3 Viking, and EA-6B Prowler.

•

Defensive Armament

—Three eight-round RIM-7 Sea Sparrow SAM point-defense missile systems.

Defensive Armament

—Three eight-round RIM-7 Sea Sparrow SAM point-defense missile systems.

All of these features added up to the biggest class of warships ever built. Only the Enterprise had dimensions, displacement, and performance anything like the proposed SCB-102 design, and “the Big E” was lugging around eight nuclear reactors, the power of which could not be fully used. SCB-102 would be a much better balanced design—a fully integrated warship that would grow and modernize as the Cold War moved into the post-Vietnam era.

On the other hand, this very impressive package was going to be expensive and difficult to build. Because of foreign competition, America’s private shipbuilding industry was in decline during the late 1960’s. At the same time, government-owned yards run by the Navy were getting out of the ship construction business altogether to concentrate on overhauls and modernization work. This meant that only one shipyard in America was large enough to build the ships of the SCB-102 design—Newport News Shipbuilding (NNS) in Virginia. By 1967, NNS had been awarded a sole-source contract for the initial units of the new

Nimitz

class (CVN- 68). These eventually included the lead ship, which was named for the World War II Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC), Admiral Chester Nimitz, and two other ships would be the

Dwight D. Eisenhower

(CVN-69—named for the former President) and the

Carl Vinson

(CVN-70—named for the Georgia senator and political architect of America’s World War II “Two Ocean Navy”).

Nimitz

class (CVN- 68). These eventually included the lead ship, which was named for the World War II Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC), Admiral Chester Nimitz, and two other ships would be the

Dwight D. Eisenhower

(CVN-69—named for the former President) and the

Carl Vinson

(CVN-70—named for the Georgia senator and political architect of America’s World War II “Two Ocean Navy”).

Secretary of the Navy John Lehman, who headed the Navy Department from 1981 to 1986 during the Administration of President Ronald W. Reagan.

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO FROM THE COLLECTION OF A. D. BAKER

It would, however, be years until all three of the new ships were completed. Labor strikes and management problems plagued the construction of

Nimitz,

which took over seven years to complete (compared with four years for

Enterprise).

All three ships wound up costing hundreds of millions of dollars more than planned, making them fat targets for Congressional critics of Pentagon “fraud, waste, and abuse.” The multi-billion-dollar price tag of the new ships meant that new carriers were going to be hard to sell to a nation that increasingly saw the military as a liability. In fact, not one new carrier was authorized by the Administration of President Jimmy Carter. However, a fourth unit of the

Nimitz

class,

Theodore Roosevelt

(CVN-71—after the late President and father of the “Great White Fleet”), was forced upon President Carter by Congress, who funded the unit in Fiscal Year 1980 (FY-80). Others would follow.

Nimitz,

which took over seven years to complete (compared with four years for

Enterprise).

All three ships wound up costing hundreds of millions of dollars more than planned, making them fat targets for Congressional critics of Pentagon “fraud, waste, and abuse.” The multi-billion-dollar price tag of the new ships meant that new carriers were going to be hard to sell to a nation that increasingly saw the military as a liability. In fact, not one new carrier was authorized by the Administration of President Jimmy Carter. However, a fourth unit of the

Nimitz

class,

Theodore Roosevelt

(CVN-71—after the late President and father of the “Great White Fleet”), was forced upon President Carter by Congress, who funded the unit in Fiscal Year 1980 (FY-80). Others would follow.

The election of President Ronald Reagan launched a period of rebirth for the Navy. This rebirth, directed at the perceived threat of a growing and aggressive Soviet “Evil Empire,” was the personal achievement of one man: then-Secretary of the Navy John Lehman. Lehman, himself a Naval aviator and heir to the wealth of a great Wall Street investment firm, called for a “600 Ship Navy,” with fifteen aircraft carriers at its core.

30

Fiscal Year 1983 (FY-83) saw the authorization of two

Nimitz-

class nuclear-powered aircraft carriers,

Abraham Lincoln

(CVN-72) and

George Washington

(CVN-73). Navy leaders dubbed this program the “Presidential Mountain,” because three of the presidents honored are carved on the Mount Rushmore monu-ment,and were strong supporters of the Navy.

31

Along with the three new carriers, over a hundred new nuclear submarines, guided-missile cruisers, destroyers, frigates, and support ships were authorized by the end of the 1980’s. It was the biggest Naval building program since the Second World War.

30

Fiscal Year 1983 (FY-83) saw the authorization of two

Nimitz-

class nuclear-powered aircraft carriers,

Abraham Lincoln

(CVN-72) and

George Washington

(CVN-73). Navy leaders dubbed this program the “Presidential Mountain,” because three of the presidents honored are carved on the Mount Rushmore monu-ment,and were strong supporters of the Navy.

31

Along with the three new carriers, over a hundred new nuclear submarines, guided-missile cruisers, destroyers, frigates, and support ships were authorized by the end of the 1980’s. It was the biggest Naval building program since the Second World War.

Before the “Presidential Mountain” was completed, the global oceanic conflict they were designed to fight (or deter, if you thought that way) evaporated. With the end of the Cold War in 1991, the supercarriers acquired new roles and missions. In operations like Desert Shield/Desert Storm (Persian Gulf—1990/1991) and Uphold Democracy (Haiti—1994), they showed their great staying power and flexibility. Meanwhile, two more

Nimitz

-class carriers had been authorized in FY-88 to replace the last two units of the

Midway

class. This was just enough to keep the NNS shipyard alive. By the early 1990’s it was time to plan on replacing the fossil-fueled carriers like

Forrestal

(CV-59) and

America

(CV-66), which were due to retire. Though at one point the Clinton Administration cut the number of carriers to eleven, the number was eventually stabilized at an even dozen (considered the minimum needed to sustain two or three forward-deployed carrier battle groups). In addition, in FY-95, another

Nimitz-

class ship was authorized, rounding out the third group of three. These three ships,

John C. Stennis

(CVN-74),

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75), and

Ronald Reagan

(CVN-76), will hold the force level at twelve.

32

Nimitz

-class carriers had been authorized in FY-88 to replace the last two units of the

Midway

class. This was just enough to keep the NNS shipyard alive. By the early 1990’s it was time to plan on replacing the fossil-fueled carriers like

Forrestal

(CV-59) and

America

(CV-66), which were due to retire. Though at one point the Clinton Administration cut the number of carriers to eleven, the number was eventually stabilized at an even dozen (considered the minimum needed to sustain two or three forward-deployed carrier battle groups). In addition, in FY-95, another

Nimitz-

class ship was authorized, rounding out the third group of three. These three ships,

John C. Stennis

(CVN-74),

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75), and

Ronald Reagan

(CVN-76), will hold the force level at twelve.

32

In many ways, the

Nimitz-

class ships represent a “worst-case” design, able to accommodate the most difficult conditions and threats. Designed against a Cold War expectation of immense Soviet conventional and nuclear firepower, they are almost too much warship for an age where there is no credible threat against them. Whether America needs so much capability right now and in the near future is a matter I’ll take up shortly. Meanwhile, let’s look at how these great ships are put together.

Newport News Shipbuilding: Home of the SupercarriersNimitz-

class ships represent a “worst-case” design, able to accommodate the most difficult conditions and threats. Designed against a Cold War expectation of immense Soviet conventional and nuclear firepower, they are almost too much warship for an age where there is no credible threat against them. Whether America needs so much capability right now and in the near future is a matter I’ll take up shortly. Meanwhile, let’s look at how these great ships are put together.

The Virginia Tidewater has been a cradle of American maritime tradition for almost four centuries. The first English colony in North America was established in 1607 on the south bank of the York Peninsula at Jamestown. Later, Hampton Roads was the scene of the world’s first fight between ironclad ships, when the USS

Monitor

and CSS

Virginia

dueled in 1862.

33

Across the James River is the port of Norfolk, the most important naval base in the United States. And along the north bank of the James River is the town of Newport News, a twenty-mile-long snake-shaped community that is the birth-place of American aircraft carriers.

Monitor

and CSS

Virginia

dueled in 1862.

33

Across the James River is the port of Norfolk, the most important naval base in the United States. And along the north bank of the James River is the town of Newport News, a twenty-mile-long snake-shaped community that is the birth-place of American aircraft carriers.

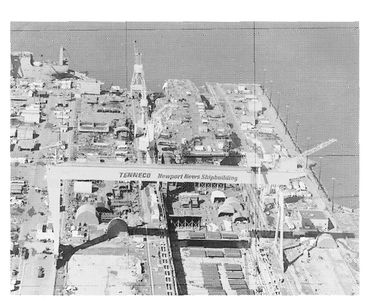

The nuclear-powered aircraft carrier

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75) being constructed at Dry Dock 12 in the Newport News Shipbuilding (NNS) yard. The large bridge crane in the foreground is used to place superlifts and other components into the dock.

Harry S. Truman

(CVN-75) being constructed at Dry Dock 12 in the Newport News Shipbuilding (NNS) yard. The large bridge crane in the foreground is used to place superlifts and other components into the dock.

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO

As you drive from Interstate 64 south onto Interstate 664, the yard makes its first appearance in the form of the huge pea-green-painted construction cranes that dominate the skyline of the city. And then as you turn off onto Washington Avenue, you will see the name on those cranes: Newport News Shipbuilding. Founded in 1886 by Collis P. Huntington, Newport News Shipbuilding (NNS) is the largest and most prosperous survivor of the American shipbuilding industry.

34

Seven of the battleships in “Teddy” Roosevelt’s “Great White Fleet” were built here. Now one of just five U.S. yards still building deep-draft warships, NNS is the largest private employer in the state of Virginia, with some eighteen thousand workers (about half of the Cold War peak). The builder of the

Ranger

(CV-4—America’s first carrier built from the keel up), NNS is the last U.S. shipyard capable of building big-deck nuclear carriers. Like most shipyards, NNS was originally built along a deep-channel river with inclined construction ways. Many of the original machine shops and dry docks are still in use after over a century of service. However, the facility has gradually been rebuilt into one of the most technically advanced and efficient shipyards in the world.

34

Seven of the battleships in “Teddy” Roosevelt’s “Great White Fleet” were built here. Now one of just five U.S. yards still building deep-draft warships, NNS is the largest private employer in the state of Virginia, with some eighteen thousand workers (about half of the Cold War peak). The builder of the

Ranger

(CV-4—America’s first carrier built from the keel up), NNS is the last U.S. shipyard capable of building big-deck nuclear carriers. Like most shipyards, NNS was originally built along a deep-channel river with inclined construction ways. Many of the original machine shops and dry docks are still in use after over a century of service. However, the facility has gradually been rebuilt into one of the most technically advanced and efficient shipyards in the world.

On the northern end of the yard you find the building area for aircraft carriers and other large ships. The centerpiece of this area is Dry Dock 12, where deep-draft ships are constructed. Almost 2,200 feet/670.6 meters long and over five stories deep, it is the largest construction dock in the Western Hemisphere. The entire area is built on landfill, with a concrete foundation supported on pilings driven through the James River silt into bedrock several hundred feet below. The concrete floor of Dry Dock 12 is particularly thick, to bear the immense weight of the ships built there. The end of the dock extends into the deep channel of the river, and is sealed off by a removable caisson (a hollow steel box). Running on tracks the length of Dry Dock 12 is a huge bridge crane, capable of lifting up to 900 tons/816.2 metric tons, while a number of smaller cranes run along the edge of the building dock. Dry Dock 12 can be split into two watertight sections by the movable caisson, so that one carrier and one or more smaller ships can be constructed at the same time.

Only a decade ago NNS could expect to start a new

Nimitz-

class aircraft carrier every two years or so. NNS also had a share of the twenty-nine planned

Seawolf-

class (SSN-21) submarines on order. There were also new classes of maritime prepositioning ships, as well as massive overhaul and modification contracts to support John Lehman’s “600 Ship Navy.” But today the outlook is dramatically different, and the number of projects under way has been scaled back radically:

Nimitz-

class aircraft carrier every two years or so. NNS also had a share of the twenty-nine planned

Seawolf-

class (SSN-21) submarines on order. There were also new classes of maritime prepositioning ships, as well as massive overhaul and modification contracts to support John Lehman’s “600 Ship Navy.” But today the outlook is dramatically different, and the number of projects under way has been scaled back radically:

• With the carrier force set at twelve flattops instead of fifteen, the U.S. only needs to build a carrier about every four years.

• The

Seawolf

program was terminated at just three boats, and the work on all three went to the General Dynamics Electric Boat Division. Thus the massive investment in specialized facilities and tooling for submarine construction will lie unused at NNS until the start of the New Attack Submarine (NSSN) program in the early 21st century.

Seawolf

program was terminated at just three boats, and the work on all three went to the General Dynamics Electric Boat Division. Thus the massive investment in specialized facilities and tooling for submarine construction will lie unused at NNS until the start of the New Attack Submarine (NSSN) program in the early 21st century.

• Now that several hundred U.S. Naval vessels are being retired because of cost and manpower, the massive overhaul and modification program is only a fraction of what was originally planned.

NNS nevertheless remains the only American shipyard capable of building nuclear-powered surface warships. If future carriers or any of their escorts are to be nuclear-powered, then NNS will build them. Since at least one more

Nimitz

-class carrier is planned (the as-yet-unnamed CVN-77), the yard will stay fat in flattop construction for another decade. Meanwhile, Congress has guaranteed NNS a share of the NSSN production with Electric Boat, allowing the company to utilize its investment in submarine construction facilities built for the

Seawolf

program years ago. There has also been a steady flow of Navy and commercial refit and modernization work, and this is proving to be highly lucrative. In fact, NNS is preparing for one of the biggest refits ever, when USS

Nimitz

(CVN-68) comes back into the yard for its first nuclear refueling.

Nimitz

-class carrier is planned (the as-yet-unnamed CVN-77), the yard will stay fat in flattop construction for another decade. Meanwhile, Congress has guaranteed NNS a share of the NSSN production with Electric Boat, allowing the company to utilize its investment in submarine construction facilities built for the

Seawolf

program years ago. There has also been a steady flow of Navy and commercial refit and modernization work, and this is proving to be highly lucrative. In fact, NNS is preparing for one of the biggest refits ever, when USS

Nimitz

(CVN-68) comes back into the yard for its first nuclear refueling.

Other books

A Shameful Secret by Ireland, Anne

El lenguaje de los muertos by Brian Lumley

Water Balloon by Audrey Vernick

Never Let You Go (a modern fairytale) by Katy Regnery

Omelette and a Glass of Wine by David, Elizabeth

Lovers and Takers by Cachitorie, Katherine

Magpie by Dare, Kim

Loving Lucius (Werescape) by Moncrief, Skhye

Grace Alive: a Christian Romance by Natasha House

The Black Witch of Mexico by Colin Falconer