Carrier (1999) (8 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

So what comes next? You have hit an “OK Three” trap, your aircraft’s tailhook has successfully caught a wire, yet you are still hurtling forward at a breathtaking speed and may fly off the forward deck edge of the “angle” at any moment if all doesn’t go well. In other words, the excitement isn’t over. Each end of the arresting wire runs though a mechanism in the deck down to a series of hydraulic ram buffers, which act to hold tension on the wire. When the aircraft’s tailhook hits the wire, the buffers dampen the energy from the aircraft, yanking it to a rapid halt. Once the aircraft stops, the pilot retracts the hook, and is rapidly taxied out of the landing zone guided by a plane handler. While this is happening, the wires are retracted to their “ready landing” position, so that another aircraft can be landed as quickly as possible. When it is done properly, modern carriers can land an aircraft every twenty to thirty seconds.

Aircraft Structures: Controlled CrashesAny combat aircraft is subjected to extraordinary stresses and strains. However, compared with your average Boeing 737 running between, say, Baltimore and Pittsburgh, carrier-capable aircraft have the added stresses of catapult launches and wire-caught landings that are actually “controlled crashes.” That means your average carrier-capable fighter or support aircraft is going to lug around a bit more muscle in its airframes than, say, a USAF F-16 operating from a land base with a nice, long, wide, concrete runway. This added robustness of carrier aircraft (compared with their land-based counterparts) is a good thing when surface-to-air missiles and antiaircraft guns are pumping ordnance in their direction. But it also means that carrier aircraft, because of their greater structural weight, have always paid a penalty in performance, payload, and range compared with similar land-based aircraft.

This structural penalty, however, may well be becoming a thing of the past. Today, aircraft designers are armed with a growing family of non-metallic structural materials (composites, carbon-carbon, etc.), as well as new design tools, such as computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) equipment. They have been finding ways to make the most recent generation of carrier aircraft light and strong, while giving them the performance to keep up with the best land-based aircraft. This is why carrier-capable aircraft like the F/A-18 Hornet have done well in export sales (Australia, Finland, and Switzerland have bought them). The Hornet gives up nothing in performance to its competitors from Lockheed Martin, Dassault-Breguet, Saab, MiG, and Sukhoi. In fact, the new generation of U.S. tactical aircraft, the JSF, may not pay any “structural” penalty at all. Current plans have all three versions (land-based, carrier-capable, and V/STOL) using the same basic structural components, which means that all three should have similar performance characteristics. Not bad for a flying machine that has to lug around the hundreds of pounds of extra structure and equipment that allow it to operate off aircraft carriers.

All of these technologies have brought carrier aircraft to their current state of the art. However, plan on seeing important changes in the next few years. For example, developments in engine technology may mean aircraft with steerable nozzles that will allow for takeoffs and landings independent of catapults and arresting wires. Whatever happens in the technology arena, count on naval aircraft designers to take advantage of every trick that will buy them a pound of payload, or a knot of speed or range. That’s because it’s a mean, cruel world out there these days!

Hand on the Helm: An Interview with Admiral Jay Johnson

Guiding Principals: Operational Primacy, Leadership,

Teamwork, and Pride.

Teamwork, and Pride.

Steer by the Stars

D

uring the long history of the U.S. Navy, there have been many inspirational examples of individuals coming out of nowhere at the time of need to lead ships, planes, and fleets on to victory. During the American Civil War, for example, a bearded, bespectacled gnome of an officer named Lieutenant John Worden took a new and untried little ship named the

Monitor

into battle. When Worden faced the mighty Confederate ironclad ram

Virginia

at Hampton Roads in 1862, his actions with the

Mon

itor saved the Union frigate

Minnesota,

the Union blockade fleet, and General George McClellan’s army from destruction.

14

More importantly, his inspired use of the little turreted ironclad forever changed the course of naval design technology, and made the wooden ship obsolete forever. There are other examples.

uring the long history of the U.S. Navy, there have been many inspirational examples of individuals coming out of nowhere at the time of need to lead ships, planes, and fleets on to victory. During the American Civil War, for example, a bearded, bespectacled gnome of an officer named Lieutenant John Worden took a new and untried little ship named the

Monitor

into battle. When Worden faced the mighty Confederate ironclad ram

Virginia

at Hampton Roads in 1862, his actions with the

Mon

itor saved the Union frigate

Minnesota,

the Union blockade fleet, and General George McClellan’s army from destruction.

14

More importantly, his inspired use of the little turreted ironclad forever changed the course of naval design technology, and made the wooden ship obsolete forever. There are other examples.

A mere half century ago, the United States Pacific Fleet was nearly destroyed by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor. Within days of the raid that brought the United States into World War II, a gravelly-voiced, leather-faced Texan named Chester Nimitz was picked to lead what was left of the Pacific Fleet against the powerful forces of Imperial Japan. Nimitz’s early Naval service (mostly spent quietly in the “pig boats” that the U.S. Navy passed off as submarines in those days) gave no indication that he was the man for the job. Nor did his later career in virtually invisible jobs at obscure (to ordinary folks) places like the Bureau of Navigation add much to that aura. When he was made CINCPAC (Commander in Chief of the Pacific), few Americans outside of his friends in the Navy even knew the man’s name. With fleet morale shattered by the events at Pearl Harbor, he hardly seemed an inspiring choice.

That opinion began to change almost immediately, when Nimitz retained many of the staff officers present at Pearl Harbor, rather than cashiering them and bringing in his own people. The men responded with total loyalty, and many were instrumental in the subsequent Allied victory in the Pacific. His action in retaining these officers, even though some commanders would have gotten rid of them for their perceived “responsibility” for the disaster, proved to be the first of an unbroken string of brilliant personnel, planning, and operational decisions. These eventually brought Nimitz to the deck of the USS

Missouri

(BB-63) in 1945 as the Navy’s representative to accept the Japanese surrender.

Missouri

(BB-63) in 1945 as the Navy’s representative to accept the Japanese surrender.

Though the Navy has been blessed with many fine leaders in its illustrious history, all the successes of the past are meaningless unless it can serve effectively today and in the future. The late 1980s and early 1990s have tested the faith of even the most fervent U.S. Navy supporters. Following what some felt was a mediocre performance during Desert Storm in 1991, the Navy suffered a string of public relations “black eyes” that included the infamous 1991 Tailhook scandal. There was worse to come. In the spring of 1996, after a media frenzy and an intense round of public criticism over both his handling of personnel matters and his own character, the popular Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), Admiral Mike Boorda, died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. The suicide of this much-admired sailor cast a pall over the entire fleet; and many in and out of the Navy began to question the quality of Navy leadership. Clearly, it was time for a top-notch leader to step up and take the helm. The man selected to take over as Chief of Naval Operations was actually much closer at hand than some would have thought—in fact, just a few doors away in the office of the Vice Chief of Naval Operations. Admiral Jay Johnson would soon start the Navy back on the road to excellence.

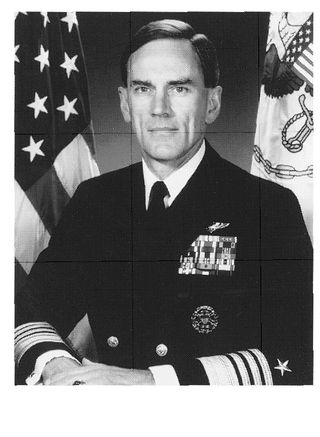

Johnson, a career naval aviator and fighter pilot, has quietly served his country and his Navy for more than three decades. A slim and trim officer who looks years younger than his age, Johnson is a quiet and sometimes shy man. But the quiet demeanor is something of a smoke screen. This man is a “doer,” who has chosen to make the hard decisions that will give the U.S. Navy a real future in the 21st century. Johnson is a passionate man, one who cares deeply about his country, his Navy, and the sailors who serve under him. He channels all that emotion into one goal: to build the U.S. Navy into a superb fighting machine, an organization that is once again the envy of military officers everywhere in the world.

Jay L. Johnson came into the world in Great Falls, Montana, on June 5th, 1946. The son of a soldier in the Army Air Corps, he spent the bulk of his youth in West Salem, Wisconsin. Let’s let him tell the story of his journey into naval service:

Admiral Jay L. Johnson, USN

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO

Tom Clancy:

Could you please tell us a little about your background and Navy career?

Could you please tell us a little about your background and Navy career?

Admiral Johnson:

I was born in Montana. My dad was serving there at the time. I didn’t stay there long—only about a year. I spent the rest of my youth in Wisconsin, in a little town with a lake near it, not far from the headwaters of the Mississippi River. That’s the total exposure to water that I had in my early years.

I was born in Montana. My dad was serving there at the time. I didn’t stay there long—only about a year. I spent the rest of my youth in Wisconsin, in a little town with a lake near it, not far from the headwaters of the Mississippi River. That’s the total exposure to water that I had in my early years.

Tom Clancy

: What made you choose the Navy as a career?

: What made you choose the Navy as a career?

Admiral Johnson:

I’d been intrigued by the military service academies as I was growing up. I had a distant relative who had gone to West Point, and was thinking about applying there myself. Then I went to a Boy Scout National Jamboree out in Colorado Springs, Colorado, in what is now the Black Forest, just down the road from the Air Force Academy. It was in 1960, I believe, about a year after the Air Force Academy had come into being. As part of our stay, we were invited to a tour there. We also got to see a show by the Thunderbirds [the Air Force precision-flight demonstration team]. As I watched that performance, and looked at that academy, I said to myself, “I can do this!” When I returned home, I decided that I’d apply to the Air Force Academy. Before I did so, I found that I had an option to go to the Naval Academy at Annapolis. I looked into it, found out a bit about carrier aviation, and decided that was what I wanted. I took that opportunity, and here I am.

I’d been intrigued by the military service academies as I was growing up. I had a distant relative who had gone to West Point, and was thinking about applying there myself. Then I went to a Boy Scout National Jamboree out in Colorado Springs, Colorado, in what is now the Black Forest, just down the road from the Air Force Academy. It was in 1960, I believe, about a year after the Air Force Academy had come into being. As part of our stay, we were invited to a tour there. We also got to see a show by the Thunderbirds [the Air Force precision-flight demonstration team]. As I watched that performance, and looked at that academy, I said to myself, “I can do this!” When I returned home, I decided that I’d apply to the Air Force Academy. Before I did so, I found that I had an option to go to the Naval Academy at Annapolis. I looked into it, found out a bit about carrier aviation, and decided that was what I wanted. I took that opportunity, and here I am.

Admiral Jay Johnson, in his Pentagon office with the author.

JOHN D. GHESHAM

Tom Clancy:

Did you have any particular “defining” experiences while at the Academy?

Did you have any particular “defining” experiences while at the Academy?

Admiral Johnson:

Well ... I got to watch Roger Staubach [the great Naval Academy and Dallas Cowboys star quarterback] play football. On a more serious note, the most striking thing I remember about my time there is how close my company mates and I became. To this day, we’re inseparable. A lot of them are still in the Navy today. Admiral Willie Moore, who is the USS

Independence

[CV-62] battle group commander, was a company mate of mine. My former roommate is the Naval attaché to India. Rear Admiral Paul Gaffney, who is the Chief of Naval Research, was also in my company. These are just a few of the people I met at the Academy who are special to me personally.

Well ... I got to watch Roger Staubach [the great Naval Academy and Dallas Cowboys star quarterback] play football. On a more serious note, the most striking thing I remember about my time there is how close my company mates and I became. To this day, we’re inseparable. A lot of them are still in the Navy today. Admiral Willie Moore, who is the USS

Independence

[CV-62] battle group commander, was a company mate of mine. My former roommate is the Naval attaché to India. Rear Admiral Paul Gaffney, who is the Chief of Naval Research, was also in my company. These are just a few of the people I met at the Academy who are special to me personally.

Tom Clancy:

Were there other notable members of the Academy classes while you were there?

Were there other notable members of the Academy classes while you were there?

Admiral Johnson:

Guys like Ollie North and Jim Webb [the former Secretary of the Navy]—and of course Roger Staubach from the class of ‘65. I have always admired him. Even then, he was a man of great integrity, courage, and superb physical prowess. What I see of Roger today matches exactly what I saw then. It’s nice to see a guy who is that solid early in his life, remain so through a highly visible career, retirement, and new career.

Guys like Ollie North and Jim Webb [the former Secretary of the Navy]—and of course Roger Staubach from the class of ‘65. I have always admired him. Even then, he was a man of great integrity, courage, and superb physical prowess. What I see of Roger today matches exactly what I saw then. It’s nice to see a guy who is that solid early in his life, remain so through a highly visible career, retirement, and new career.

Tom Clancy:

You graduated during the depths of the Vietnam conflict [1968]. Were you immediately sent out to flight school and into the Replacement Air Group [RAG]?

You graduated during the depths of the Vietnam conflict [1968]. Were you immediately sent out to flight school and into the Replacement Air Group [RAG]?

Admiral Johnson: Well, they did move us through at a nice pace, though I don’t remember it being any kind of “rush” job. I went through flight training in pretty much a normal time frame. I got my wings in October of 1969. From there I headed out to San Diego and NAS Miramar to learn to fly the F-8 Crusader.

Tom Clancy:

You must have been there with some living legends, men like “Hot Dog” Brown and Jim “Ruff” Ruffelson, right?

You must have been there with some living legends, men like “Hot Dog” Brown and Jim “Ruff” Ruffelson, right?

Other books

Lost Between Houses by David Gilmour

7 Tales of Sex and Betrayal by Zita Weber

The Changelings (War of the Fae: Book 1) by Casey, Elle

Curse of the Fae King by Fortune, Kryssie

Dark World: Into the Shadows with the Lead Investigator of the Ghost Adventures Crew by Crigger, Kelly, Bagans, Zak

The Greatcoat by Helen Dunmore

Behind Her Smile by Rosemary Hines

Lemonade Mouth by Mark Peter Hughes

Sugar Cube by Kir Jensen

Love is for Ever by Barbara Rowan