Carrier (1999) (9 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

Admiral Johnson:

Yes, they were there. Being one of the F-8 “MiG Killers” was kind of the unusual for a new guy back then. It was the time when a lot of the guys fresh out of the Academy were getting orders to F-4’s [Phantom IIs], and most of us were lined up to get into the Phantom community because they were new and they were hot! More than a few of us wound up flying F-8’s though, and in retrospect it was the best thing that ever happened to me. The F-8 was an awesome airplane. And, as good as the airplane was, the community of people who flew and supported it was even better. We’re all still pretty tight. We have F-8 Crusader reunions every year.

Yes, they were there. Being one of the F-8 “MiG Killers” was kind of the unusual for a new guy back then. It was the time when a lot of the guys fresh out of the Academy were getting orders to F-4’s [Phantom IIs], and most of us were lined up to get into the Phantom community because they were new and they were hot! More than a few of us wound up flying F-8’s though, and in retrospect it was the best thing that ever happened to me. The F-8 was an awesome airplane. And, as good as the airplane was, the community of people who flew and supported it was even better. We’re all still pretty tight. We have F-8 Crusader reunions every year.

Tom Clancy:

Could you tell us a little about your experiences in the Crusader?

Could you tell us a little about your experiences in the Crusader?

Admiral Johnson:

I had about a thousand hours in the Crusader. I did two combat cruises to Vietnam in VF-191 aboard the USS

Oriskany

[CVA-34], in 1970 and 1972. As I recall, we went out for a long cruise, came back for a short time, and then did an even longer cruise. In all that time, I only had one backseat ride in a Phantom. I think I may be one of the few naval aviators of my generation who has never flown an F-4. From the Crusader I went straight into the F-14 Tomcat.

I had about a thousand hours in the Crusader. I did two combat cruises to Vietnam in VF-191 aboard the USS

Oriskany

[CVA-34], in 1970 and 1972. As I recall, we went out for a long cruise, came back for a short time, and then did an even longer cruise. In all that time, I only had one backseat ride in a Phantom. I think I may be one of the few naval aviators of my generation who has never flown an F-4. From the Crusader I went straight into the F-14 Tomcat.

Tom Clancy:

From your record, it looks like you spent the majority of your career in the Tomcat community.

From your record, it looks like you spent the majority of your career in the Tomcat community.

Admiral Johnson:

That’s right. I did my department head tour and my squadron command tour in Tomcats. However, when I went to become an air wing commander, I tried to fly most of the air wing airplanes. The planes I flew back then included the A-7 Corsair, which is like a stubby-nosed cousin to the F-8 without an afterburner. I also flew the A-6 Intruder. Later, on my second CAG [Commander, Air Group—the traditional nickname for an Air Wing Commander dating back to the beginnings of carrier aviation], on my battle group command tour, I wound up flying the F/A-18 Hornet. I still remember flying the F-8, though. Your first jet assignment is like your first love. It’s where everything is defined for you.

That’s right. I did my department head tour and my squadron command tour in Tomcats. However, when I went to become an air wing commander, I tried to fly most of the air wing airplanes. The planes I flew back then included the A-7 Corsair, which is like a stubby-nosed cousin to the F-8 without an afterburner. I also flew the A-6 Intruder. Later, on my second CAG [Commander, Air Group—the traditional nickname for an Air Wing Commander dating back to the beginnings of carrier aviation], on my battle group command tour, I wound up flying the F/A-18 Hornet. I still remember flying the F-8, though. Your first jet assignment is like your first love. It’s where everything is defined for you.

Tom Clancy:

Following your time in F-8’s, you seem to have spent most of your time in the East Coast units. Is that correct?

Following your time in F-8’s, you seem to have spent most of your time in the East Coast units. Is that correct?

Admiral Johnson:

It’s correct, but it really wasn’t a conscious decision on my part. I guess it just worked out that way. Initially, when I learned to fly the Tomcat, I headed back out to the West Coast and went through the F-14 RAG [Replacement Air Group], VF-124. Then I was moved back to the East Coast, where I have pretty much stayed ever since.

It’s correct, but it really wasn’t a conscious decision on my part. I guess it just worked out that way. Initially, when I learned to fly the Tomcat, I headed back out to the West Coast and went through the F-14 RAG [Replacement Air Group], VF-124. Then I was moved back to the East Coast, where I have pretty much stayed ever since.

Tom Clancy:

Obviously, you spent an eventful couple of decades with the fleet in the 1970’s and 80’s. Can you tell us a few of the things that stand out in your mind?

Obviously, you spent an eventful couple of decades with the fleet in the 1970’s and 80’s. Can you tell us a few of the things that stand out in your mind?

Admiral Johnson:

The Vietnam experience stands out, of course. The operations against Libya in the 80’s were interesting—Operations Prairie Fire and Eldorado Canyon [the bombing of Libya in April 1986]. I was in and out of there several times during that period. I also remember the day that Commander Hank Kleeman and the guys from VF-41 [the Black Aces] “splashed” two Libyan Sukhois back in [August] 1981. I was sitting in flight deck control [on the USS

Nimitz

[CVN-68], getting ready to man up and recycle one of the combat air patrol [CAP] stations. The plan was to land the first pair of F-14 Tomcats. Then I was going to be part of the second “go” of the day. It was announced over the 1MC [the master public address system on board the ship] that something “big” had just happened. When the two F-14’s that had shot down the two Libyan fighter-bombers got back aboard, everyone wanted to look at the planes and see what had happened.

The Vietnam experience stands out, of course. The operations against Libya in the 80’s were interesting—Operations Prairie Fire and Eldorado Canyon [the bombing of Libya in April 1986]. I was in and out of there several times during that period. I also remember the day that Commander Hank Kleeman and the guys from VF-41 [the Black Aces] “splashed” two Libyan Sukhois back in [August] 1981. I was sitting in flight deck control [on the USS

Nimitz

[CVN-68], getting ready to man up and recycle one of the combat air patrol [CAP] stations. The plan was to land the first pair of F-14 Tomcats. Then I was going to be part of the second “go” of the day. It was announced over the 1MC [the master public address system on board the ship] that something “big” had just happened. When the two F-14’s that had shot down the two Libyan fighter-bombers got back aboard, everyone wanted to look at the planes and see what had happened.

Tom Clancy:

You came into this job [as Chief of Naval Operations, or CNO] at a time of great crisis and turmoil for the Navy. Among other issues, Admiral Boorda’s death was a great blow to the Navy. What were the important things that you had to do when you arrived?

You came into this job [as Chief of Naval Operations, or CNO] at a time of great crisis and turmoil for the Navy. Among other issues, Admiral Boorda’s death was a great blow to the Navy. What were the important things that you had to do when you arrived?

Admiral Johnson:

It was important to me to make sure, because of Admiral Boorda’s reputation as a sailor in the fleet, that the officers and sailors in the fleet knew that things were going to be “O.K.” I sent out an “all hands” message to that effect, and spent the next eight or nine months traveling around the world to get the message out to the people in the fleet.

It was important to me to make sure, because of Admiral Boorda’s reputation as a sailor in the fleet, that the officers and sailors in the fleet knew that things were going to be “O.K.” I sent out an “all hands” message to that effect, and spent the next eight or nine months traveling around the world to get the message out to the people in the fleet.

Tom Clancy:

As CNO, you seem to have a unique working partnership with Secretary of the Navy John Dalton, and the Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Charles “Chuck” Krulak. Can you tell us about that relationship?

As CNO, you seem to have a unique working partnership with Secretary of the Navy John Dalton, and the Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Charles “Chuck” Krulak. Can you tell us about that relationship?

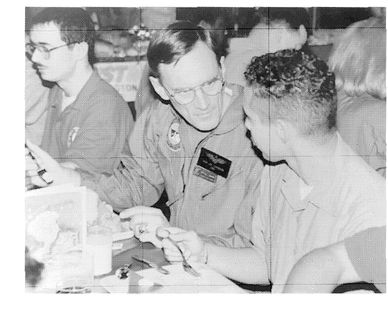

Admiral Jay Johnson eating a 1997 holiday meal with sailors aboard ship in the Persian Gulf.

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO

Admiral Johnson:

As you know, before I got here, Secretary Dalton made the decision to relocate the Commandant of the Marine Corps and most of his staff from the old Navy Annex up the hill to the E-Ring of the Pentagon. So now Secretary Dalton’s office is bracketed by the Commandant’s office on one side, and the CNO’s on the other. He’s got us in stereo! The decision to move the Marine Corps Commandant was a powerful one, in my opinion. The relationship between Secretary Dalton and Chuck Krulak was already in place even before I arrived. When I got here as Vice CNO, and particularly as I made the transition to CNO, both men were very understanding, supportive, and helpful. I could not have asked for a better welcome.

As you know, before I got here, Secretary Dalton made the decision to relocate the Commandant of the Marine Corps and most of his staff from the old Navy Annex up the hill to the E-Ring of the Pentagon. So now Secretary Dalton’s office is bracketed by the Commandant’s office on one side, and the CNO’s on the other. He’s got us in stereo! The decision to move the Marine Corps Commandant was a powerful one, in my opinion. The relationship between Secretary Dalton and Chuck Krulak was already in place even before I arrived. When I got here as Vice CNO, and particularly as I made the transition to CNO, both men were very understanding, supportive, and helpful. I could not have asked for a better welcome.

Tom Clancy:

It sounds like the three of you have forged a special working relationship on this end of the E-Ring corridor. Is that true?

It sounds like the three of you have forged a special working relationship on this end of the E-Ring corridor. Is that true?

Admiral Johnson:

The short answer is

yes!

These relationships work very well due to a number of factors. First of all, Chuck Krulak and I are friends. He and I are close personally, as are our wives. That’s a good start to a professional relationship, but there’s more to it than that. We share some important common goals. For example, we are both making a concerted effort to lead our sailors and marines to work well together in this age of cooperation and coordination between the various branches of the military. I mean, how the hell are you going to do that, if the top sailor and marine can’t get along?

The short answer is

yes!

These relationships work very well due to a number of factors. First of all, Chuck Krulak and I are friends. He and I are close personally, as are our wives. That’s a good start to a professional relationship, but there’s more to it than that. We share some important common goals. For example, we are both making a concerted effort to lead our sailors and marines to work well together in this age of cooperation and coordination between the various branches of the military. I mean, how the hell are you going to do that, if the top sailor and marine can’t get along?

The relevance of the sea services, both the Navy

and

the Marine Corps, is that we’re the forward presence for our country in virtually any military operation. We’re there first, and we’re out last. It’s essential that we coordinate our forces to do the job as well as it can be done. We’re proud of our mission, proud of our people, and proud of our ability to do the job together. That’s the strength that we give to the country.

and

the Marine Corps, is that we’re the forward presence for our country in virtually any military operation. We’re there first, and we’re out last. It’s essential that we coordinate our forces to do the job as well as it can be done. We’re proud of our mission, proud of our people, and proud of our ability to do the job together. That’s the strength that we give to the country.

Now, just because we’re trying to work together on our various missions does not mean that the job of coordinating the Navy and the Marine Corps is an easy one, either for Chuck and me, or for the other officers and enlisted soldiers on our staffs. We work with some very challenging issues, and we aren’t always able to agree completely on every point we discuss. As in any working relationship, there are occasional conflicts.

Admiral Jay Johnson relaxing in his Pentagon office during his interview with the author.

JOHN D. GRESHAM

But we’re committed to working through them and formulating solutions. The principles that underlie our working partnership and the friendship between Chuck and me girds it all and makes it possible for us to work through those hard decisions. This benefits both services. Both Chuck and I have the support and guidance of Secretary Dalton as well. I think we have a pretty good team.

Tom Clancy:

As we all know, it’s been a challenging decade for the Navy. In addition to issues like Tailhook and Admiral Boorda’s death, there were real problems that had been building for over two decades. You were placed in charge of a Navy whose ships had been run hard during the Cold War years. Can you tell us a bit about the state of the fleet today?

As we all know, it’s been a challenging decade for the Navy. In addition to issues like Tailhook and Admiral Boorda’s death, there were real problems that had been building for over two decades. You were placed in charge of a Navy whose ships had been run hard during the Cold War years. Can you tell us a bit about the state of the fleet today?

Admiral Johnson:

Despite the many challenges we’re had to endure, the Navy has carried on wonderfully, in my view, in terms of reacting to the requirements that have been levied upon it. Our mission as the nation’s forward-deployed force means we have to be prepared to respond at all times to any situation in which we are needed. The relevance of that mission will not change as we go into the 21 st century. I believe we are ready. That’s what we do, seven days a week, 365 days a year. I think that one of the greatest challenges that we face in the Navy is reassuring the American people of the level of our commitment to the mission to serve and protect them. This is important, because for a lot of people, what we do is sort of “off of the radarscope.”

Despite the many challenges we’re had to endure, the Navy has carried on wonderfully, in my view, in terms of reacting to the requirements that have been levied upon it. Our mission as the nation’s forward-deployed force means we have to be prepared to respond at all times to any situation in which we are needed. The relevance of that mission will not change as we go into the 21 st century. I believe we are ready. That’s what we do, seven days a week, 365 days a year. I think that one of the greatest challenges that we face in the Navy is reassuring the American people of the level of our commitment to the mission to serve and protect them. This is important, because for a lot of people, what we do is sort of “off of the radarscope.”

Tom Clancy:

Given what you have just said, how is the fleet bearing up under this extremely high Operations Tempo [Optempo]?

Given what you have just said, how is the fleet bearing up under this extremely high Operations Tempo [Optempo]?

Admiral Johnson:

That’s a question that requires an answer on more than one level. There is no denying that our sailors, by the very nature of their work, spend time away from their homes and families. Some of the things that we are looking at are ways to make sure that we don’t overstretch ourselves.

That’s a question that requires an answer on more than one level. There is no denying that our sailors, by the very nature of their work, spend time away from their homes and families. Some of the things that we are looking at are ways to make sure that we don’t overstretch ourselves.

Right now we have a policy that says that ships will have no more than six months forward-deployed at sea, from portal to portal. We’re also maintaining a ratio of two-to-one for time at home port to deployed time, and no more than fifty percent of time out of home port when you are off deployment.

We are adhering to that policy, and I am the only one who can waive it for any reason. In fact, whether we are standing by that policy is one of my own measures of whether we are “stretching the rubber band too tight,” where people are concerned. So right now, we’re OK with that situation. Now, we have had a couple of exceptions to this rule last year because of problems with ship maintenance in a yard that closed down. The result is that in terms of readiness and execution, the fleet is “answering on all bells.” I want to make sure as you walk back from looking at deployment issues, that everyone is getting enough training to get ready, but not so much that their home lives suffer. We also want to make sure that the right equipment is available during training, so that the fleet fights with the same gear it trains with.

Tom Clancy:

How is retention of personnel holding up?

How is retention of personnel holding up?

Admiral Johnson:

Retention right now is good, though there are pockets of concern in that situation. If you look, for instance, at pilot retention numbers, the aggregate numbers, they’re great. They’re not even worth talking about today. There is no problem there. Within that community, though, if you “peel that onion” back a layer, we’re beginning to see that we need to pay attention to the attrition rates of some kinds of air crews.

Retention right now is good, though there are pockets of concern in that situation. If you look, for instance, at pilot retention numbers, the aggregate numbers, they’re great. They’re not even worth talking about today. There is no problem there. Within that community, though, if you “peel that onion” back a layer, we’re beginning to see that we need to pay attention to the attrition rates of some kinds of air crews.

In my view, these situations are not developing just because the airlines are hiring. The airlines are

always

hiring, and will continue to hire. That’s a reality that we can’t change. But I do think that part of this softness in community retention is based upon the “turnaround” and non-deployed side of a Naval career.

always

hiring, and will continue to hire. That’s a reality that we can’t change. But I do think that part of this softness in community retention is based upon the “turnaround” and non-deployed side of a Naval career.

In particular, we need to make sure that we’re not keeping people too far from home for too much time doing temporary kinds of assignments. We need to make sure that we don’t have backlogs in aircraft and equipment depot maintenance, so that our crews have enough airplanes to fly during turnarounds and workups. We also have to pay attention to the matter of funding enough flying hours to keep our people sharp. Let’s face it, junior officers [JOs] never get enough flight hours. I know that I didn’t as a young aviator, and I don’t know anyone who did. We’ve still got some work to do in that area.

These “soft” community areas are not just limited to naval aviation. We’ve got some year groups in the submarine community that we’re watching carefully, as well as some in the surface warfare professionals. Overall, though, we’re OK. On the enlisted side the numbers are excellent, and most significantly, the high quality of personnel is there.

These days, we’re having to work very hard to get that quality, and it’s a real challenge. The goal of our recruiting is to have ninety-five-percent high school graduates, with sixty-five percent of those recruits in the top mental group in their classes. When we achieve that, it’s good for the fleet, and we’re committed to achieving that.

However, the competition for that part of the labor market is really intense out there. Given the pressures of a healthy economy, I think that it’s going to be more and more of a challenge. The

really

good young men and women out there—the ones who are really smart and talented—everybody wants them. Frankly, while I can offer them a lot, there are other folks who can offer them more of things like money. Still, there are wonderful and patriotic young folks who take up the challenge, and we work hard to find them and keep them in the fleet.

really

good young men and women out there—the ones who are really smart and talented—everybody wants them. Frankly, while I can offer them a lot, there are other folks who can offer them more of things like money. Still, there are wonderful and patriotic young folks who take up the challenge, and we work hard to find them and keep them in the fleet.

Trust me when I say that the recruiting challenges will not go away. Remember, back in the Cold War we had to bring around 100,000 new recruits a year into the fleet to fill our needs. Today, even in a time of relative peace, we still need between 45,000 and fifty thousand new bsailors every year to keep our force healthy and running.

Other books

Dealer and his Bestowed Bride (The Rossi Family Mafia Book 2) by Avery Hawkes

Obsession in Death by J. D. Robb

Tattered Innocence by Ann Lee Miller

In Your Room by Jordanna Fraiberg

The Shoulders of Giants by Jim Cliff

The Forbidden Tomb by Kuzneski, Chris

Stroke of Midnight by Sherrilyn Kenyon, Amanda Ashley, L. A. Banks, Lori Handeland

Heart of Stone by Warren, Christine

Fire Time by Poul Anderson

The Locket by Stacey Jay