Carrier (1999) (16 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

What kind of person does the Navy want to fly its airplanes? For starters, he or she has to be a college graduate from an accredited four-year university.

22

Prior to World War II, the Naval Academy supplied the majority of naval aviation cadets. But when the war demanded a vastly expanded pool of air crews, the requirements for naval aviation cadets were lowered to completion of just two years of college. Today, the sea services feel that the responsibility for flying a fifty-million-dollar aircraft (with more computing and sensor power than a whole fleet just a generation ago) should go to someone with a university education. For a modern pilot will have to be a systems operator, tactician, and athlete, as well as a naval officer with duties to lead and manage.

22

Prior to World War II, the Naval Academy supplied the majority of naval aviation cadets. But when the war demanded a vastly expanded pool of air crews, the requirements for naval aviation cadets were lowered to completion of just two years of college. Today, the sea services feel that the responsibility for flying a fifty-million-dollar aircraft (with more computing and sensor power than a whole fleet just a generation ago) should go to someone with a university education. For a modern pilot will have to be a systems operator, tactician, and athlete, as well as a naval officer with duties to lead and manage.

Once you have the college degree, and assuming that you want to fly over the water for your country, that your eyesight and physical condition are good, and that you can pass the required batteries of mental and coordination tests, what else do you need? First, you need to be an officer in the U.S. Navy or U.S. Marine Corps.

23

If you are a graduate of the Naval Academy (or, for that matter, West Point or Colorado Springs), then you have automatically earned a reserve officer’s commission as an ensign or 2nd lieutenant.

24

The same is true if you have completed an accredited Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) program at a university. However, if you are a simple college graduate with an ambition to fly for the sea services, then there are several Officer Candidate Schools (OCSs) that can give you the basic skills as a Navy or Marine Corps officer, as well as the commission. Though there were once a number of these schools around the country, today there are just two, one at Quantico, Virginia, for the Marines, and the Navy school at Pensacola, Florida. However you get the commission to ensign/2nd lieutenant (O-1), the path to the cockpit of an aircraft in the sea services starts at Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola.

NAS Pensacola: Cradle of Naval Aviation23

If you are a graduate of the Naval Academy (or, for that matter, West Point or Colorado Springs), then you have automatically earned a reserve officer’s commission as an ensign or 2nd lieutenant.

24

The same is true if you have completed an accredited Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) program at a university. However, if you are a simple college graduate with an ambition to fly for the sea services, then there are several Officer Candidate Schools (OCSs) that can give you the basic skills as a Navy or Marine Corps officer, as well as the commission. Though there were once a number of these schools around the country, today there are just two, one at Quantico, Virginia, for the Marines, and the Navy school at Pensacola, Florida. However you get the commission to ensign/2nd lieutenant (O-1), the path to the cockpit of an aircraft in the sea services starts at Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola.

NAS Pensacola, on the shore of the bay whose name it borrows, was originally founded as a Naval Aeronautical Station in 1914. But the region’s relationship with the Navy goes back much further. The bay itself, discovered in the 16th century by the Spanish explorer Don Tristan de Luna, attracted official U.S. Navy interest in the early 1800s because of its proximity to high-quality timber reserves, a staple of l9th century shipbuilding. Starting in 1825, the Navy built yard facilities near the site of the present-day NAS. From this Naval station came patrols that suppressed the slave trade and piracy in the mid-1800s. Destroyed by retreating Confederate forces during the Civil War, the base was rebuilt shortly after the end of that conflict. Severely damaged again by hurricane and tidal events in 1906, the excellent location and facilities proved too valuable to surrender to the elements, and the base was not only rebuilt, but also expanded.

The Flightline at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida. Every Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard aviator starts his or her career at this base.

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO

Pensacola’s association with naval aviation began in 1913, when recommendations were made to establish an aviation training station in a location with a year-round climate that was favorable to the needs of early aviators. Opened in 1914, it was the home to a rapidly expanding aviation force that by the end of World War I included fixed-wing aircraft, seaplanes, dirigibles, and even kites and balloons! But the lean years following the war meant that only about a hundred new aviators per year were being trained. That time ended in the 1930s with the creation of Naval Aviation Cadet Training Program, which was designed to expand the air crew population in anticipation of the coming world war. To support the growth in the training program, several other training bases were constructed, including NAS Corpus Christi, Texas, and NAS Jacksonville, Florida. Eventually, the combined U.S. naval flight training facilities were turning out over 1,100 new naval aviators a month, though this was reduced following the end of World War II. On average, during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, about two thousand naval aviators a year were trained to meet wartime requirements, while more peaceful times saw that number drop to around 1,500. Today, NAS Pensacola is the home of a still-robust naval air crew training capability.

Training: Into the PipelineSoon after an aviation cadet arrives at Pensacola, he or she has to make a major decision: whether to train to become a Naval Aviator (NA—pilot) or Naval Flight Officer (NFO—airborne systems operator). Or rather, just about everybody starts out wanting to be pilots, but then the decision about which way to go is often made for them when the vision test results come in. Eyesight is the first great pass/fail point among fliers. In general, the services look for good distance vision, though excellent night vision is also desired. Many of those who wind up as NFOs do so because they fail the initial eyesight cut for pilots. As it happens, though, life as an NFO very rarely proves disappointing. More often than you might believe, squadron and air wing commands are won by NFOs, many of whom have been noted for their superior leadership and management skills.

Whichever career path beckons the incoming cadets, they all start training in the same classroom. Specifically, there’s a six-week course known as Aviation Preflight Indoctrination (API), which comprises a syllabus designed to bring all of the Student Naval Aviators (SNAs) and Student Naval Flight Officers (SNFOs) up to a common knowledge and skill base. API covers aerodynamics, engineering, navigation, and physiology. Along with the classroom work, the students receive physical training in water survival, physical conditioning, and emergency escape procedures. API “levels” the skill base of the cadets, and provides a fighting chance to those who did not (for example) study physics or computer science in college. When API is completed, the training pipeline splits into two separate conduits. One of these is the Primary Flight Training (PFT) pipeline for SNFOs, while the other is for SNAs wanting to pilot Naval aircraft.

Pilot Training: The SNA PipelineSNA PFT is designed to teach pretty much the same basic flight skills that a civilian would need to obtain a private pilot’s license. It consists of some sixty-six hours of flight training, as well as a syllabus of ground classroom and simulator training. The actual flight training includes basic aerobatics, formation flying, and military flight procedures. This is quite similar to that of the Army and USAF. However, the way that training is conducted has recently changed a great deal for all U.S. military air personnel. These changes have resulted from the 1986 Goldwater-Nichols defense reform legislation. Specifically, Goldwater-Nichols encouraged the Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps to find ways to combine common tasks into “joint” (i.e., multi-service) programs and units. The consequence for pilot training has been to combine primary/undergraduate flight training, as well as training for a number of different missions and airframes. To that end, the services have established joint training squadrons around the country. They have further teamed up to build a new common primary/undergraduate trainer, the T-6A Texan II, which will enter service in 1999. Based upon the Swiss Pilatus PC-9 turboprop trainer, it will provide a truly economical joint training solution for primary/undergraduate flight training.

Thus a young SNA going through PFT in 1997 might be found at Vance AFB near Enid, Oklahoma. Assigned to the 8th Flying Training Squadron (FTS), he will have done his PFT flight training in an Air Force T-37B, in a joint unit commanded by a naval officer, Commander Mark S. Laughton. Similar squadrons are located at NAS Pensacola, Randolph AFB and NAS Corpus Christi in Texas, as well as other bases. Since the joint training squadrons have proved successful, plans are under way to provide joint training at the airframe level where it is appropriate. For example, since all the services with fixed-wing aircraft fly variants of the venerable C-130 Hercules, there will soon be a single C-130 pipeline unit for training the air crews.

At the end of the PFT phase of training, cadets find out what “community” they will be headed for at the completion of their training. Though just a fraction the size of the USAF, the air forces of the sea services are even more diverse in their roles and missions. Therefore, following the basic phase of PFT, cadets move onto one of five training pipelines (all of which have intermediate and advanced phases). These include:

•

Strike (Tactical Jets)

—This course of training provides student trainees for the F-14 Tomcat, F/A-18 Hornet, AV-8B Harrier II, EA-6B Prowler, S-3 Viking, and ES-3 Shadow aircraft. Normally, strike pipeline SNAs train at the same base where they did their PFT work. Along with further classroom work in aerodynamics, engineering, meteorology, communications, and navigation, there is flying. A lot of flying! All told, the intermediate and advanced phases of the strike pipeline PFT provide for around 150 flight hours, covering a great range of required skills and knowledge. These include flight instruction in visual and instrument flying, precision aerobatics, gunnery/weapons delivery, high- and low-altitude flight, air combat maneuvering (ACM), and formation flying. Night flying is also taught, along with flying in a variety of weather conditions, and radar approaches/landings. During this time also comes the dreaded carrier qualification, where the SNA meets up with the deck of an actual aircraft carrier for the first time. To help the students along, extensive use is made of part-task trainers based upon personal computers (PCs), as well as high-end full-motion simulators. However, no amount of simulation and preparation can insure that everyone completes the roughly sixteen-month course.

Strike (Tactical Jets)

—This course of training provides student trainees for the F-14 Tomcat, F/A-18 Hornet, AV-8B Harrier II, EA-6B Prowler, S-3 Viking, and ES-3 Shadow aircraft. Normally, strike pipeline SNAs train at the same base where they did their PFT work. Along with further classroom work in aerodynamics, engineering, meteorology, communications, and navigation, there is flying. A lot of flying! All told, the intermediate and advanced phases of the strike pipeline PFT provide for around 150 flight hours, covering a great range of required skills and knowledge. These include flight instruction in visual and instrument flying, precision aerobatics, gunnery/weapons delivery, high- and low-altitude flight, air combat maneuvering (ACM), and formation flying. Night flying is also taught, along with flying in a variety of weather conditions, and radar approaches/landings. During this time also comes the dreaded carrier qualification, where the SNA meets up with the deck of an actual aircraft carrier for the first time. To help the students along, extensive use is made of part-task trainers based upon personal computers (PCs), as well as high-end full-motion simulators. However, no amount of simulation and preparation can insure that everyone completes the roughly sixteen-month course.

For years, this phase of training had the SNAs flying either the T-2C Buckeye or TA-4J Skyhawk, both classic two-seat training aircraft. But a long-overdue replacement is finally coming into service after a series of problems and delays. Known as the T-45 Goshawk training system, it is based upon a heavily modified British Aerospace Hawk trainer, and is designed to provide a beginning-to-end training for the Strike pipeline. This means that the contractor (Boeing, through the acquisition of McDonnell Douglas) provides everything required—simulators, computer-based-trainers, the T-45 training aircraft, and all the maintenance personnel. In order to make the training system work for PFT students, the sea services only need to provide personnel (instructors and students), a base, and fuel. The newest version, the T-45C, incorporates a fully functional “glass” cockpit, similar to the F/A-18’s and that of other modern tactical aircraft that the students will eventually fly.

25

The T-45C can be used for a much more varied curriculum than the two aircraft it replaces ; and thanks to a fuel-efficient engine and all the new avionics systems, the T-45 training system will actually not only save money, but also improve the quality and fidelity of the various training curriculums.

25

The T-45C can be used for a much more varied curriculum than the two aircraft it replaces ; and thanks to a fuel-efficient engine and all the new avionics systems, the T-45 training system will actually not only save money, but also improve the quality and fidelity of the various training curriculums.

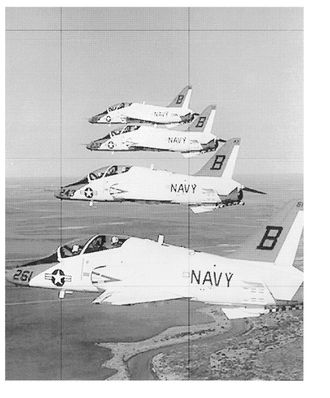

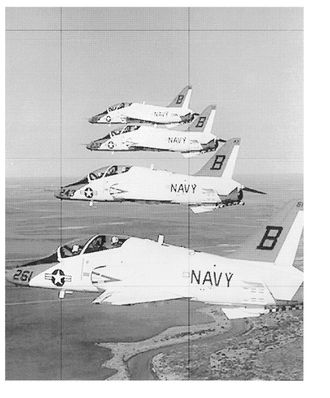

A flight of Boeing T-45 Goshawk trainers. Based on the British Aerospace Hawk-series trainers, they provide the Navy with an economical jet trainer that is replacing the aging T-2 Buckeye and TA-4 Skyhawk.

BOEING MILTTARY AIRCRAFT

•

E-2/C2

—This training course supplies air crews to fly the E-2C Hawkeye airborne early-warning aircraft and its transport cousin, the C-2 Greyhound, both of which are powered by twin-engine turboprops. Because the airframes that it supplies air crews for are among the most heavily loaded and difficult to fly on and off carriers, the E-2/C-2 pipeline is unique. Thus, for example, the E-2/C-2 pipeline deletes some of the combat/weapons-oriented portions of the Strike PFT course work. Utilizing the T-44A Pegasus (essentially a twin-engine Raytheon/Beech King Air), the intermediate training is carried out by Naval Training Squadron 31 (VT-31), and is run at NAS Corpus Christi, Texas. The advanced phase is handled by VT-4 at NAS Pensacola, Florida, flying T-45’s.

E-2/C2

—This training course supplies air crews to fly the E-2C Hawkeye airborne early-warning aircraft and its transport cousin, the C-2 Greyhound, both of which are powered by twin-engine turboprops. Because the airframes that it supplies air crews for are among the most heavily loaded and difficult to fly on and off carriers, the E-2/C-2 pipeline is unique. Thus, for example, the E-2/C-2 pipeline deletes some of the combat/weapons-oriented portions of the Strike PFT course work. Utilizing the T-44A Pegasus (essentially a twin-engine Raytheon/Beech King Air), the intermediate training is carried out by Naval Training Squadron 31 (VT-31), and is run at NAS Corpus Christi, Texas. The advanced phase is handled by VT-4 at NAS Pensacola, Florida, flying T-45’s.

•

Maritime—Since

the sea services fly several types of four-engine turboprop aircraft (the P-3/EP-3 Orion and C-130/KC-130/HC-130 Hercules), a separate pipeline (Maritime) supports these communities. The Maritime syllabus begins with six additional weeks of flying at the primary PFT base. For the remaining twenty weeks of the course (intermediate and advanced), the students fly the T-44A Pegasus with VT-31 at NAS Corpus Christi for an additional eighty-four flight hours of instruction. Since these aircraft never land on carriers, the syllabus concentrates on multi-engine aircraft operating procedures, especially in emergency and all-weather operations.

Maritime—Since

the sea services fly several types of four-engine turboprop aircraft (the P-3/EP-3 Orion and C-130/KC-130/HC-130 Hercules), a separate pipeline (Maritime) supports these communities. The Maritime syllabus begins with six additional weeks of flying at the primary PFT base. For the remaining twenty weeks of the course (intermediate and advanced), the students fly the T-44A Pegasus with VT-31 at NAS Corpus Christi for an additional eighty-four flight hours of instruction. Since these aircraft never land on carriers, the syllabus concentrates on multi-engine aircraft operating procedures, especially in emergency and all-weather operations.

•

E-6

—One of the more chilling missions flown by naval aviators (a mission unique to the Navy) involves flying the E-6 Mercury—the TACMO (Take Charge and Move Out) aircraft. TACMO was originally the control function for the Navy’s Trident Fleet Ballistic Missile (FBM) submarines, but its mission has grown. Based on a Boeing 707 airframe, the E-6 Mercury is packed with secure communications and battle-management equipment. Along with the gear for the TACMO mission, the E-6 carries a fully equipped battle staff from the U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM—BASED at Offut AFB near Omaha, Nebraska). This allows the E-6’s to control the launch and weapons release of

all

U.S. nuclear forces (bombers, land-based missiles, and sub-launched missiles) from a (relatively !) secure airborne command post (this job was previously handled by the USAF fleet of EC-135 Looking Glass aircraft). In the event that a nuclear strike were to destroy the National Command Authorities in Washington, D.C., and other land-based locations, the TACMO aircraft would still be able to order a counterstrike.

E-6

—One of the more chilling missions flown by naval aviators (a mission unique to the Navy) involves flying the E-6 Mercury—the TACMO (Take Charge and Move Out) aircraft. TACMO was originally the control function for the Navy’s Trident Fleet Ballistic Missile (FBM) submarines, but its mission has grown. Based on a Boeing 707 airframe, the E-6 Mercury is packed with secure communications and battle-management equipment. Along with the gear for the TACMO mission, the E-6 carries a fully equipped battle staff from the U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM—BASED at Offut AFB near Omaha, Nebraska). This allows the E-6’s to control the launch and weapons release of

all

U.S. nuclear forces (bombers, land-based missiles, and sub-launched missiles) from a (relatively !) secure airborne command post (this job was previously handled by the USAF fleet of EC-135 Looking Glass aircraft). In the event that a nuclear strike were to destroy the National Command Authorities in Washington, D.C., and other land-based locations, the TACMO aircraft would still be able to order a counterstrike.

To support this highly specialized mission, the Navy has a specific pipeline to supply air crews for this single type of airframe. While generally like the Maritime pipeline, the multi-engine-trainer time is carried out on the new T-1A Jayhawk Tanker/Transport Trainer System (TTTS—based on the Raytheon/Beech 400A business jet). Like the T-45 training system, the Jayhawk training curriculum makes extensive use of computerized task trainers and simulators. Overall, the E-6 pipeline emphasizes all-weather flight techniques and cockpit resource management.

•

Helicopter—Since

about half of sea service aircraft are helicopters, the rotorcraft course of study is second only to the strike pipeline in numbers of aviators trained. The Helicopter intermediate-phase PFT is composed of six additional weeks at the primary training base, with an emphasis on instrument flying. This is followed by the twenty-one-week advanced phase of the Helicopter pipeline, which is composed of 116 hours of flight training in the TH-57B/C Sea Ranger helicopter (the Navy’s trainer version of the famous Bell Jet Ranger business/utility helicopter). Along with the flying, the classroom work includes helicopter aerodynamics and engineering, night and cross-country flying, as well as combat search-and-rescue techniques. Finally, the Helicopter pipeline SNAs actually take off and land from the Helicopter Landing Trainer (HLT), a specially configured barge at NAS Pensacola.

Helicopter—Since

about half of sea service aircraft are helicopters, the rotorcraft course of study is second only to the strike pipeline in numbers of aviators trained. The Helicopter intermediate-phase PFT is composed of six additional weeks at the primary training base, with an emphasis on instrument flying. This is followed by the twenty-one-week advanced phase of the Helicopter pipeline, which is composed of 116 hours of flight training in the TH-57B/C Sea Ranger helicopter (the Navy’s trainer version of the famous Bell Jet Ranger business/utility helicopter). Along with the flying, the classroom work includes helicopter aerodynamics and engineering, night and cross-country flying, as well as combat search-and-rescue techniques. Finally, the Helicopter pipeline SNAs actually take off and land from the Helicopter Landing Trainer (HLT), a specially configured barge at NAS Pensacola.

Other books

You're Married to Her? by Ira Wood

The Darwin Effect by Mark Lukens

One Plus Two Minus One by Tess Mackenzie

Begging for Trouble by McCoy, Judi

Drown by Junot Diaz

Drip Dry by Ilsa Evans

Runaway by Marie-Louise Jensen

Iorich by Steven Brust

In the Shade of the Monkey Puzzle Tree by Sara Alexi

Her Accidental Boyfriend: A Secret Wishes Novel (Entangled Bliss) by Bielman, Robin