Carrier (1999) (19 page)

Authors: Tom - Nf Clancy

American Supercarriers: A History

Nimitz-

Class (CVN-68) Supercarriers

The atomic bombs that forced Japan to capitulate in 1945 almost sank the U.S. Navy’s force of carriers. With the end of the war, as a cost-saving measure, most U.S. carriers were either scrapped or mothballed. And by 1947, the wartime fleet of over one hundred carriers had shrunk to less than two dozen vessels. Meanwhile, President Harry S Truman had decreed a moratorium on new weapons development, except for nuclear weapons and bombers to carry them. The Navy, desperate for a mission in the atomic age, began to design a carrier and aircraft that could deliver the new weapons.

27

The USS

United States

(CVA-58—the “A” stood for “Atomic” combat), would have been the biggest carrier ever built from the keel up (65,000 tons displacement). The Navy argued that immobile overseas Air Force bases were vulnerable to political pressure and Soviet preemptive attack, while carriers, secure in the vast spaces of the Norwegian Sea, the Barents Sea, or the Mediterranean, could launch nuclear strikes on Soviet Naval bases or deep into the Russian heartland.

27

The USS

United States

(CVA-58—the “A” stood for “Atomic” combat), would have been the biggest carrier ever built from the keel up (65,000 tons displacement). The Navy argued that immobile overseas Air Force bases were vulnerable to political pressure and Soviet preemptive attack, while carriers, secure in the vast spaces of the Norwegian Sea, the Barents Sea, or the Mediterranean, could launch nuclear strikes on Soviet Naval bases or deep into the Russian heartland.

Claiming that the newly created Air Force could better deliver the new atomic weapons with their huge new B-36 bombers, Air Force leaders like General Carl “Tooey” Spaatz lobbied intensively to kill the new carrier program. By persuading the Truman Administration that they could deliver nuclear weapons more cheaply than the Navy, the Air Force succeeded in having the

United States

broken up on the building ways just days after her keel was laid (April 23rd, 1949). Soon afterward, the Secretary of the Navy, John L. Sullivan, resigned in protest, leading to the “Revolt of the Admirals” (discussed in the first chapter), which allowed the Navy to make a public case for conventional naval forces. Once the Truman Administration realized the political cost of killing the

United States,

the cuts in naval forces were stopped. It was just in time, as events turned out. For the carriers recently judged obsolete in an age of atomic warfare held the line in the conventional war that erupted in Korea on the morning of June 25th, 1950.

United States

broken up on the building ways just days after her keel was laid (April 23rd, 1949). Soon afterward, the Secretary of the Navy, John L. Sullivan, resigned in protest, leading to the “Revolt of the Admirals” (discussed in the first chapter), which allowed the Navy to make a public case for conventional naval forces. Once the Truman Administration realized the political cost of killing the

United States,

the cuts in naval forces were stopped. It was just in time, as events turned out. For the carriers recently judged obsolete in an age of atomic warfare held the line in the conventional war that erupted in Korea on the morning of June 25th, 1950.

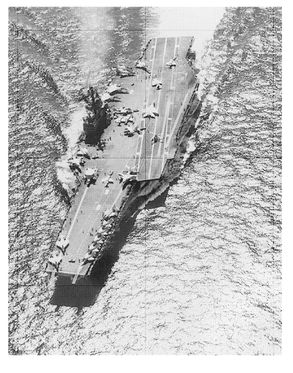

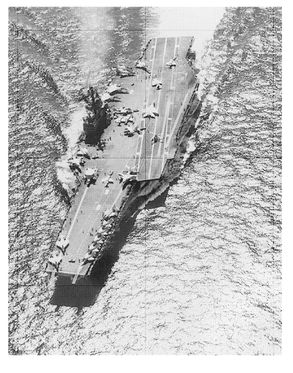

The USS

Forrestal

(CV-59), the first of America’s supercarriers. She is cruising here in the Gulf of Tonkin during combat operations in 1967.

Forrestal

(CV-59), the first of America’s supercarriers. She is cruising here in the Gulf of Tonkin during combat operations in 1967.

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO FROM THE COLLECTION OF A. D. BAKER

Even before the end of the Korean War, the Truman Administration recognized the need for new, bigger, more modern aircraft carriers. Though he was never a friend of the Navy, President Truman nevertheless belatedly authorized construction of a new class of “supercarriers” similar to the

United States,

canceled just three years earlier. The first of the new flattops was USS

Forrestal

(CVA-59—the “A” now reflecting the new “Attack” carrier designation), which was followed by three sister ships:

Saratoga

(CVA-60),

Ranger

(CVA-61), and

Independence

(CVA-62). These were huge vessels, at 1,039 feet/316 meters in length and almost sixty thousand tons displacement. The

Forrestal

class incorporated a number of innovations, almost all of British origin. A 14° angled deck enabled planes to land safely on the angled section, while other planes were catapulting off the bow. Steam catapults allowed larger aircraft to be launched. Also, a stabilized landing light system guided pilots aboard more reliably than the old system of handheld signal paddles. Along with the new carriers came the first-generation naval jet aircraft. Meanwhile, the Navy initiated a huge Fleet Rebuilding and Modernization (FRAM) program for older carriers and other ships, both to give them another twenty years or so of service life and to delay the need to buy so many expensive new ships like

Forrestal.

United States,

canceled just three years earlier. The first of the new flattops was USS

Forrestal

(CVA-59—the “A” now reflecting the new “Attack” carrier designation), which was followed by three sister ships:

Saratoga

(CVA-60),

Ranger

(CVA-61), and

Independence

(CVA-62). These were huge vessels, at 1,039 feet/316 meters in length and almost sixty thousand tons displacement. The

Forrestal

class incorporated a number of innovations, almost all of British origin. A 14° angled deck enabled planes to land safely on the angled section, while other planes were catapulting off the bow. Steam catapults allowed larger aircraft to be launched. Also, a stabilized landing light system guided pilots aboard more reliably than the old system of handheld signal paddles. Along with the new carriers came the first-generation naval jet aircraft. Meanwhile, the Navy initiated a huge Fleet Rebuilding and Modernization (FRAM) program for older carriers and other ships, both to give them another twenty years or so of service life and to delay the need to buy so many expensive new ships like

Forrestal.

The USS

Enterprise

(CVN-65), the world’s first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. Here she is cruising in the Mediterranean Sea with the nuclear cruisers

Long Beach

(CGN-9) and

Bainbridge

(CGN-26) during Operation Sea Orbit in 1964.

Enterprise

(CVN-65), the world’s first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. Here she is cruising in the Mediterranean Sea with the nuclear cruisers

Long Beach

(CGN-9) and

Bainbridge

(CGN-26) during Operation Sea Orbit in 1964.

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO FROM THE COLLECTION OF A. D. BAKER

The first Cold War confrontation in which aircraft carriers played a major role was the Suez Crisis in 1956; carrier groups assigned to the U.S. Sixth Fleet spent the next year supporting operations by U.S. Marines and other forces trying to restore stability in Lebanon following the Arab-Israeli war. In 1958, Task Force 77 got a workout in the Far East when it interposed between the forces of Taiwan and Communist China during the crisis over the islands of Quemoy and Matsu. Meanwhile, two new follow-on supercarriers were ordered—

Kitty Hawk

(CVA-63) in 1956 and

Constellation

(CVA-64) in 1957. Essentially improved and enlarged

Forrestal

-class vessels, they approached the upper limits of size and capability for oil-fueled carriers. The time had come for a break with fossil-fueled power plants, and the carrier that followed was truly revolutionary.

Kitty Hawk

(CVA-63) in 1956 and

Constellation

(CVA-64) in 1957. Essentially improved and enlarged

Forrestal

-class vessels, they approached the upper limits of size and capability for oil-fueled carriers. The time had come for a break with fossil-fueled power plants, and the carrier that followed was truly revolutionary.

The successful development of nuclear reactors to propel submarines encouraged the Navy to put them in surface ships. Backed by the mercurial Director of Naval Reactors, Vice Admiral Hyman Rickover, an improved Kitty Hawk design was developed to accommodate a nuclear propulsion plant. Ever eager to maximize the influence of nuclear power in the Navy, Admiral Rickover dictated that the new carrier should have just as many nuclear reactors (eight!) as there were oil-fired boilers in each

Kitty Hawk

-class carrier. When the new carrier, designated USS

Enterprise

(CVAN-65), was commissioned in the early 1960’s, she was so overpowered that the structure of the ship could not stand the pounding of a full-power run. There are stories of speed runs off the Virginia capes in which the

Enterprise

went so fast (some say over forty knots; the actual numbers are still classified), that she left her destroyer escorts far behind, without tapping her full power.

Kitty Hawk

-class carrier. When the new carrier, designated USS

Enterprise

(CVAN-65), was commissioned in the early 1960’s, she was so overpowered that the structure of the ship could not stand the pounding of a full-power run. There are stories of speed runs off the Virginia capes in which the

Enterprise

went so fast (some say over forty knots; the actual numbers are still classified), that she left her destroyer escorts far behind, without tapping her full power.

Though

Enterprise

more than lived up to the heritage of her proud name, she was to be a one-of-a-kind ship.

28

Then-Secretary of Defense Robert S. MacNamara, no friend of the Navy, blocked construction of more nuclear-powered carriers. Over the next decade, only two new carriers,

America

(CVA-66) and

John F. Kennedy

(CVA-67), would be constructed. These flattops, essentially repeats of the earlier

Kitty Hawk

-class, were powered by oil-fired boilers. After MacNamara’s resignation in 1968, the ban on nuclear carrier construction lifted, and the Navy received authorization for a new class of three nuclear-powered attack carriers. This would become the mighty

Nimitz

-class (CVN-68) program.

Enterprise

more than lived up to the heritage of her proud name, she was to be a one-of-a-kind ship.

28

Then-Secretary of Defense Robert S. MacNamara, no friend of the Navy, blocked construction of more nuclear-powered carriers. Over the next decade, only two new carriers,

America

(CVA-66) and

John F. Kennedy

(CVA-67), would be constructed. These flattops, essentially repeats of the earlier

Kitty Hawk

-class, were powered by oil-fired boilers. After MacNamara’s resignation in 1968, the ban on nuclear carrier construction lifted, and the Navy received authorization for a new class of three nuclear-powered attack carriers. This would become the mighty

Nimitz

-class (CVN-68) program.

A side view of an improved

Nimitz-Class

(CVN-68) nuclear-powered aircraft carrier.

Nimitz-Class

(CVN-68) nuclear-powered aircraft carrier.

JACK RYAN ENTERPRISES, LTD., BY LAURA DENINNO

TheNimitz-

Class (CVN-68) Supercarriers

Because of the vast base of experience developed over the previous four decades, even before design of the

Nimitz

-class carriers began in the late 1960’s, the Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) had a number of good ideas about what they wanted from their next generation of flattops. Frankly, they wanted a lot! The largest warships (in dimensions and displacement) ever planned at the time, the

Nimitz-

class carriers were to be the ultimate expression of sea-based airpower. Some of the “fighting” qualities of the

Nimitz-

class included:

Nimitz

-class carriers began in the late 1960’s, the Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) had a number of good ideas about what they wanted from their next generation of flattops. Frankly, they wanted a lot! The largest warships (in dimensions and displacement) ever planned at the time, the

Nimitz-

class carriers were to be the ultimate expression of sea-based airpower. Some of the “fighting” qualities of the

Nimitz-

class included:

•

Aircraft Capacity

—For over seventy-five years the value of a flattop has been measured by the number and types of aircraft it can carry. Ever since the Navy learned that the original USS

Ranger

was too small to carry a credible air wing, U.S. carrier designs have emphasized big flight and hangar decks to park, stow, and operate aircraft.

28

In addition, growth in the size and weight of combat aircraft has driven the design of carriers. For example, an F4F Wildcat fighter of 1941 left the deck at a maximum weight of 7,952 lb/3,607 kg, but today’s F-14 Tomcat fighter has a maximum takeoff weight of 74,348 lb/33,724 kg! The

Nimitz

-class carriers were designed to handle ninety or more aircraft (though they currently operate with air groups of about seventy-five), depending on “spot factor” (the amount of deck space each aircraft type requires).

Aircraft Capacity

—For over seventy-five years the value of a flattop has been measured by the number and types of aircraft it can carry. Ever since the Navy learned that the original USS

Ranger

was too small to carry a credible air wing, U.S. carrier designs have emphasized big flight and hangar decks to park, stow, and operate aircraft.

28

In addition, growth in the size and weight of combat aircraft has driven the design of carriers. For example, an F4F Wildcat fighter of 1941 left the deck at a maximum weight of 7,952 lb/3,607 kg, but today’s F-14 Tomcat fighter has a maximum takeoff weight of 74,348 lb/33,724 kg! The

Nimitz

-class carriers were designed to handle ninety or more aircraft (though they currently operate with air groups of about seventy-five), depending on “spot factor” (the amount of deck space each aircraft type requires).

•

Armament

—Experience with heavy guns and long-range surface-to-air missile (SAM) batteries on earlier classes of aircraft carriers proved that the deck space, interior volume, manpower demands, and blast effects of such weapons interfered with air operations, the carrier’s true reason for existence. Therefore, weapons on newer carriers would be limited to point defense (i.e., “last ditch” self-defense) systems like the RIM-7 Sea Sparrow surface-to-air missile (SAM) and Mk. 15 Phalanx/CIWS 20mm automatic cannon. A few .50-caliber machine guns would also be mounted for defense against suicide motor boats or terrorist swimmers.

Armament

—Experience with heavy guns and long-range surface-to-air missile (SAM) batteries on earlier classes of aircraft carriers proved that the deck space, interior volume, manpower demands, and blast effects of such weapons interfered with air operations, the carrier’s true reason for existence. Therefore, weapons on newer carriers would be limited to point defense (i.e., “last ditch” self-defense) systems like the RIM-7 Sea Sparrow surface-to-air missile (SAM) and Mk. 15 Phalanx/CIWS 20mm automatic cannon. A few .50-caliber machine guns would also be mounted for defense against suicide motor boats or terrorist swimmers.

•

Crew Size

—For centuries, experience has shown that the more sailors you cram aboard a warship, the better her fighting qualities, especially when you need to repair battle damage. On the other hand, sailors take up a lot of space, and generate large “hotel” loads on the ship’s power plant (for electricity, water, heating, and cooling) that have nothing to do with fighting. Modern sailors are volunteers, who expect a minimum level of comfort. The Royal Navy’s eighteen-inch spacing between hammocks aboard warships two centuries ago may have worked for impressed seamen, but would hardly do for today’s sailors. Therefore, naval designers are constantly balancing the advantages of larger crews with the costs of personnel on ship size and capability. The

Nimitz-

class carriers would be designed to sail with about six thousand personnel on board: 155 officers and 2,980 sailors for the ship; 365 officers and 2,500 enlisted personnel for the air wing. Now add an admiral’s staff, a few dozen civilian contractors to maintain the high-tech equipment, and a constant trickle of distinguished visitors and media representatives, and a carrier can get really crowded!

Crew Size

—For centuries, experience has shown that the more sailors you cram aboard a warship, the better her fighting qualities, especially when you need to repair battle damage. On the other hand, sailors take up a lot of space, and generate large “hotel” loads on the ship’s power plant (for electricity, water, heating, and cooling) that have nothing to do with fighting. Modern sailors are volunteers, who expect a minimum level of comfort. The Royal Navy’s eighteen-inch spacing between hammocks aboard warships two centuries ago may have worked for impressed seamen, but would hardly do for today’s sailors. Therefore, naval designers are constantly balancing the advantages of larger crews with the costs of personnel on ship size and capability. The

Nimitz-

class carriers would be designed to sail with about six thousand personnel on board: 155 officers and 2,980 sailors for the ship; 365 officers and 2,500 enlisted personnel for the air wing. Now add an admiral’s staff, a few dozen civilian contractors to maintain the high-tech equipment, and a constant trickle of distinguished visitors and media representatives, and a carrier can get really crowded!

•

Deployability

—Since a crisis may be halfway around the world, a carrier needs to go fast. On the other hand, high speed is worthless if the carrier does not carry sufficient fuel to get where it has to go without frequent refueling. The interior space consumed by a large power plant and its fuel is not available for aircraft, crew berthing, ammunition, jet fuel, and other useful stowage. In the final analysis, the choice of a nuclear power plant was a no-brainer. The

Nimitz-

class carriers were designed to carry two General Electric A4W/A1G nuclear reactors, and were expected to operate for fifteen years between refuelings.

29

That’s up to one million nautical miles of steaming on just one set of reactor cores.

Deployability

—Since a crisis may be halfway around the world, a carrier needs to go fast. On the other hand, high speed is worthless if the carrier does not carry sufficient fuel to get where it has to go without frequent refueling. The interior space consumed by a large power plant and its fuel is not available for aircraft, crew berthing, ammunition, jet fuel, and other useful stowage. In the final analysis, the choice of a nuclear power plant was a no-brainer. The

Nimitz-

class carriers were designed to carry two General Electric A4W/A1G nuclear reactors, and were expected to operate for fifteen years between refuelings.

29

That’s up to one million nautical miles of steaming on just one set of reactor cores.

The carrier USS

George Washington

(CVN-73) conducting an underway replenishment (UNREP) from the fleet logistics ship USS

Seattle

(AOE-3). UNREP is a vital capability in keeping battle groups forward-deployed, and utilizes both “high lines” and helicopters to transfer cargo and fuel.

George Washington

(CVN-73) conducting an underway replenishment (UNREP) from the fleet logistics ship USS

Seattle

(AOE-3). UNREP is a vital capability in keeping battle groups forward-deployed, and utilizes both “high lines” and helicopters to transfer cargo and fuel.

OFFICIAL U.S. NAVY PHOTO

•

Sustainability

—Once a carrier has reached an operating area, it must conduct operations for as long as possible without resupply since it may take weeks for fleet supply vessels to catch up with the carrier battle group. The enemy may not wait while you replenish at sea, so the amount of fuel, food, ammunition, and spare parts carried on board has a direct effect on how long a carrier can stay in action. It is also essential when fleet supply vessels reach the carriers; for when carriers are conducting Underway Replenishment (UNREP), basic safety rules dictate that they cannot operate aircraft or maneuver freely. Thus, the less often they take aboard fuel and supplies, the more time they can spend “on the line” conducting combat operations. The

Nimitz-

class carriers were designed to store up to nine thousand tons of jet fuel and almost two thousand tons of bombs, ammunition, and missiles. This is a vast improvement over earlier designs.

Sustainability

—Once a carrier has reached an operating area, it must conduct operations for as long as possible without resupply since it may take weeks for fleet supply vessels to catch up with the carrier battle group. The enemy may not wait while you replenish at sea, so the amount of fuel, food, ammunition, and spare parts carried on board has a direct effect on how long a carrier can stay in action. It is also essential when fleet supply vessels reach the carriers; for when carriers are conducting Underway Replenishment (UNREP), basic safety rules dictate that they cannot operate aircraft or maneuver freely. Thus, the less often they take aboard fuel and supplies, the more time they can spend “on the line” conducting combat operations. The

Nimitz-

class carriers were designed to store up to nine thousand tons of jet fuel and almost two thousand tons of bombs, ammunition, and missiles. This is a vast improvement over earlier designs.

•

Survivability

—All of the above are worthless if the carrier is a blazing hulk about to turn turtle and sink.

Nimitz-

class carriers were designed in an era when the threat of Soviet cruise missiles and torpedoes armed with 1,000-kg/2,200-lb warheads was quite real. These weapons could blow a cruiser or destroyer in half, and do considerable harm to an aircraft carrier. The Navy was especially conscious of these dangers after three deadly fires aboard USN carriers during the Vietnam War had taken a high toll of lives, aircraft, and equipment. Remember that these ships are basically big boxes filled with explosives, jet fuel, and people, all packed tightly together. With all this in mind, the NAVSEA designers went to extreme lengths to make the new carriers both durable and survivable. The flight and hangar decks, as well as the hull, would be built from high-tensile steel, with a vast scheme of compartmentation and built-up structure. In addition, the new flattop would make only minimal use of light metals like aluminum, which are flammable under some easily reached fire conditions.

Survivability

—All of the above are worthless if the carrier is a blazing hulk about to turn turtle and sink.

Nimitz-

class carriers were designed in an era when the threat of Soviet cruise missiles and torpedoes armed with 1,000-kg/2,200-lb warheads was quite real. These weapons could blow a cruiser or destroyer in half, and do considerable harm to an aircraft carrier. The Navy was especially conscious of these dangers after three deadly fires aboard USN carriers during the Vietnam War had taken a high toll of lives, aircraft, and equipment. Remember that these ships are basically big boxes filled with explosives, jet fuel, and people, all packed tightly together. With all this in mind, the NAVSEA designers went to extreme lengths to make the new carriers both durable and survivable. The flight and hangar decks, as well as the hull, would be built from high-tensile steel, with a vast scheme of compartmentation and built-up structure. In addition, the new flattop would make only minimal use of light metals like aluminum, which are flammable under some easily reached fire conditions.

Other books

Trapper Boy by Hugh R. MacDonald

Nobody's Baby by Carol Burnside

One Hundred Facets of Mr. Diamonds Vol.1- Aglow by Green, Emma

Sweet Redemption (The Pregnancy Affair Book 3 by Silver, Jordan

Battle for The Abyss by Ben Counter

Tell Me a Story (The Story Series Book 1) by Tamara Lush

Manties in a Twist (The Subs Club Book 3) by J.A. Rock

The Pretty Committee Strikes Back by Lisi Harrison

9781618851666FindingHisSomethingSpicyLabelle by Unknown