Civilization: The West and the Rest (11 page)

By comparison with the patchwork quilt of Europe, East Asia was – in political terms, at least – a vast monochrome blanket. The Middle Kingdom’s principal competitors were the predatory Mongols to the north and the piratical Japanese to the east. Since the time of Qin Shihuangdi – often referred to as the ‘First Emperor’ of China (221–210

BC

) – the threat from the north had been the bigger one – the one that necessitated the spectacular investment in imperial defence we know today as the Great Wall. Nothing remotely like it was constructed in Europe from the time of Hadrian to the time of Erich Honecker. Comparable in scale was the network of canals and ditches that irrigated China’s arable land, which the Marxist Sinologist Karl Wittfogel saw as the most important products of a ‘hydraulic-bureaucratic’ Oriental despotism.

The Forbidden City in Beijing is another monument to monolithic Chinese power. To get a sense of its immense size and distinctive ethos, the visitor should walk through the Gate of Supreme Harmony to the Hall of Supreme Harmony, which contains the Dragon Throne itself, then to the Hall of Central Harmony, the emperor’s private room, and then to the Hall of Preserving Harmony, the site of the final stage of the imperial civil service examination (see below). Harmony ( ), it seems clear, was inextricably bound up with the idea of undivided imperial authority.

), it seems clear, was inextricably bound up with the idea of undivided imperial authority.

37

Like the Great Wall, the Forbidden City simply had no counterpart in the fifteenth-century West, least of all in London, where power was subdivided between the Crown, the Lords Temporal and Spiritual and the Commons, as well as the Corporation of the City of London and the livery companies. Each had their palaces and halls, but they were all very small by Oriental standards. In the same way, while medieval European kingdoms were run by a combination of hereditary landowners and clergymen, selected (and often ruthlessly discarded) on the basis of royal favour, China was ruled from the top down by a

Confucian bureaucracy, recruited on the basis of perhaps the most demanding examination system in all history. Those who aspired to a career in the imperial service had to submit to three stages of gruelling tests conducted in specially built exam centres, like the one that can still be seen in Nanjing today – a huge walled compound containing thousands of tiny cells little larger than the lavatory on a train:

These tiny brick compartments [a European traveller wrote] were about 1.1 metres deep, 1 metre wide and 1.7 metres high. They possessed two stone ledges, one servicing as a table, the other as a seat. During the two days an examination lasted the candidates were observed by soldiers stationed in the lookout tower … The only movement allowed was the passage of servants replenishing food and water supplies, or removing human waste. When a candidate became tired, he could lay out his bedding and take a cramped rest. But a bright light in the neighbouring cell would probably compel him to take up his brush again … some candidates went completely insane under the pressure.

38

No doubt after three days and two nights in a shoebox, it was the most able – and certainly the most driven – candidates who passed the examination. But with its strong emphasis on the Four Books and Five Classics of Confucianism, with their bewildering 431,286 characters to be memorized, and the rigidly stylized eight-legged essay introduced in 1487, it was an exam that rewarded conformity and caution.

39

It was fiercely competitive, no doubt, but it was not the kind of competition that promotes innovation, much less the appetite for change. The written language at the heart of Chinese civilization was designed for the production of a conservative elite and the exclusion of the masses from their activities. The contrast could scarcely be greater with the competing vernaculars of Europe – Italian, French and Castilian as well as Portuguese and English – usable for elite literature but readily accessible to a wider public with relatively simple and easily scalable education.

40

As Confucius himself said: ‘A common man marvels at uncommon things. A wise man marvels at the commonplace.’ But there was too much that was commonplace in the way Ming China worked, and too little that was new.

Civilizations are complex things. For centuries they can flourish in a sweet spot of power and prosperity. But then, often quite suddenly, they can tip over the edge into chaos.

The Ming dynasty in China had been born in 1368, when the warlord Yuanzhang renamed himself Hongwu, meaning ‘vast military power’. For most of the next three centuries, as we have seen, Ming China was the world’s most sophisticated civilization by almost any measure. But then, in middle of the seventeenth century, the wheels came flying off. This is not to exaggerate its early stability. Yongle had, after all, succeeded his father Hongwu only after a period of civil war and the deposition of the rightful successor, his eldest brother’s son. But the mid-seventeenth-century crisis was unquestionably a bigger disruption. Political factionalism was exacerbated by a fiscal crisis as the falling purchasing power of silver eroded the real value of tax revenues.

41

Harsh weather, famine and epidemic disease opened the door to rebellion within and incursions from without.

42

In 1644 Beijing itself fell to the rebel leader Li Zicheng. The last Ming Emperor hanged himself out of shame. This dramatic transition from Confucian equipoise to anarchy took little more than a decade.

The results of the Ming collapse were devastating. Between 1580 and 1650 conflict and epidemics reduced the Chinese population by between 35 and 40 per cent. What had gone wrong? The answer is that turning inwards was fatal, especially for a complex and densely populated society like China’s. The Ming system had created a high-level equilibrium – impressive outwardly, but fragile inwardly. The countryside could sustain a remarkably large number of people, but only on the basis of an essentially static social order that literally ceased to innovate. It was a kind of trap. And when the least little thing went wrong, the trap snapped shut. There were no external resources to draw on. True, a considerable body of scholarship has sought to represent Ming China as a prosperous society, with considerable internal trade and a vibrant market for luxury goods.

43

The most recent Chinese research, however, shows that per-capita income stagnated in the Ming era and the capital stock actually shrank.

44

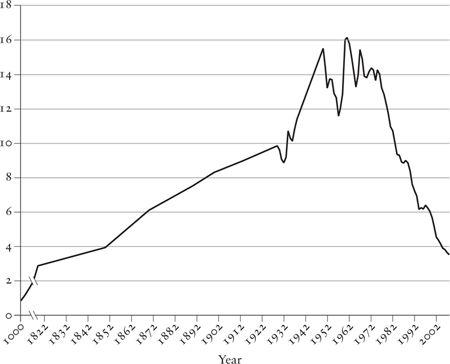

UK/China per capita GDP Ratio, 1000–2008

By contrast, as England’s population accelerated in the late seventeenth century, overseas expansion played a vital role in propelling the country out of the Malthusian trap. Transatlantic trade brought an influx of new nutrients like potatoes and sugar – an acre of sugar cane yielded the same amount of energy as 12 acres of wheat

45

– as well as plentiful cod and herring. Colonization allowed the emigration of surplus population. Over time, the effect was to raise productivity, incomes, nutrition and even height.

Consider the fate of another island people, situated much like the English on an archipelago off the Eurasian coast. While the English aggressively turned outwards, laying the foundations of what can justly be called ‘Anglobalization’, the Japanese took the opposite path, with the Tokugawa shogunate’s policy of strict seclusion (

sakoku

) after 1640. All forms of contact with the outside world were proscribed. As a result, Japan missed out entirely on the benefits associated with a rapidly rising level of global trade and migration. The results were striking. By the late eighteenth century, more than 28 per cent of

the English farmworker’s diet consisted of animal products; his Japanese counterpart lived on a monotonous intake, 95 per cent cereals, mostly rice. This nutritional divergence explains the marked gap in stature that developed after 1600. The average height of English convicts in the eighteenth century was 5 feet 7 inches. The average height of Japanese soldiers in the same period was just 5 feet 2½ inches.

46

When East met West by that time, they could no longer look one another straight in the eye.

In other words, long before the Industrial Revolution, little England was pulling ahead of the great civilizations of the Orient because of the material advantages of commerce and colonization. The Chinese and Japanese route – turning away from foreign trade and intensifying rice cultivation – meant that with population growth, incomes fell, and so did nutrition, height and productivity. When crops failed or their cultivation was disrupted, the results were catastrophic. The English were luckier in their drugs, too: long habituated to alcohol, they were roused from inebriation in the seventeenth century by American tobacco, Arabic coffee and Chinese tea. They got the stimulation of the coffee house, part café, part stock exchange, part chat-room;

47

the Chinese ended up with the lethargy of the opium den, their pipes filled by none other than the British East India Company.

48

Not all European commentators recognized, as Adam Smith did, China’s ‘stationary state’. In 1697 the German philosopher and mathematician Leibniz announced: ‘I shall have to post a notice on my door: Bureau of Information for Chinese Knowledge.’ In his book

The Latest News from China

, he suggested that ‘Chinese missionaries should be sent to us to teach the aims and practice of natural theology, as we send missionaries to them to instruct them in revealed religion.’ ‘One need not be obsessed with the merits of the Chinese,’ declared the French

philosophe

Voltaire in 1764, ‘to recognize … that their empire is in truth the best that the world has ever seen.’ Two years later the Physiocrat François Quesnay published

The Despotism of China

, which praised the primacy of agriculture in Chinese economic policy.

Yet those on the other side of the Channel who concerned themselves more with commerce and industry – and who were also less inclined to idealize China as a way of obliquely criticizing their own

government – discerned the reality of Chinese stagnation. In 1793 the 1st Earl Macartney led an expedition to the Qianlong Emperor, in a vain effort to persuade the Chinese to reopen their empire to trade. Though Macartney pointedly declined to kowtow, he brought with him ample tribute: a German-made planetarium, ‘the largest and most perfect glass lens that perhaps was ever fabricated’, as well as telescopes, theodolites, air-pumps, electrical machines and ‘an extensive apparatus for assisting to explain and illustrate the principles of science’. Yet the ancient Emperor (he was in his eighties) and his minions were unimpressed by these marvels of Western civilization:

it was presently discovered that the taste [for the sciences], if it ever existed, was now completely worn out … [All] were … lost and thrown away on the ignorant Chinese … who immediately after the departure of the embassador [

sic

] are said to have piled them up in lumber rooms of Yuen-min-yuen [the Old Summer Palace]. Not more successful were the various specimens of elegance and art displayed in the choicest examples of British manufactures. The impression which the contemplation of such articles seemed to make on the minds of the courtiers was that alone of jealousy … Such conduct may probably be ascribed to a kind of state policy, which discourages the introduction of novelties …

The Emperor subsequently addressed a dismissive edict to King George III: ‘There is nothing we lack,’ he declared. ‘We have never set much store on strange or ingenious objects, nor do we need any more of your country’s manufactures.’

49