Civilization: The West and the Rest (9 page)

Other Chinese innovations include chemical insecticide, the fishing reel, matches, the magnetic compass, playing cards, the toothbrush and the wheelbarrow. Everyone knows that golf was invented in Scotland. Yet the Dongxuan Records from the Song dynasty (960–1279) describe a game called

chuiwan

. It was played with ten clubs, including a

cuanbang

,

pubang

and

shaobang

, which are roughly analogous to our driver, two-wood and three-wood. The clubs were inlaid with jade and gold, suggesting that golf, then as now, was a game for the well-off.

And that was not all. As a new century dawned in 1400, China was poised to achieve another technological breakthrough, one that had the potential to make the Yongle Emperor the master not just of the Middle Kingdom, but of the world itself – literally ‘All under heaven’.

In Nanjing today you can see a full-size replica of the treasure ship of Admiral Zheng He, the most famous sailor in Chinese history. It is 400 feet long – nearly five times the size of the

Santa María

, in which Christopher Columbus crossed the Atlantic in 1492. And this was only part of a fleet of more than 300 huge ocean-going junks. With multiple masts and separate buoyancy chambers to prevent them from sinking in the event of a hole below the waterline, these ships

were far larger than anything being built in fifteenth-century Europe. With a combined crew of 28,000, Zheng He’s navy was bigger than anything seen in the West until the First World War.

Their master and commander was an extraordinary man. At the age of eleven, he had been captured on the field of battle by the founder of the Ming dynasty, Zhu Yuanzhang. As was customary, the captive was castrated. He was then assigned as a servant to the Emperor’s fourth son, Zhu Di, the man who would seize and ascend the imperial throne as Yongle. In return for Zheng He’s loyal service, Yongle entrusted him with a task that entailed exploring the world’s oceans.

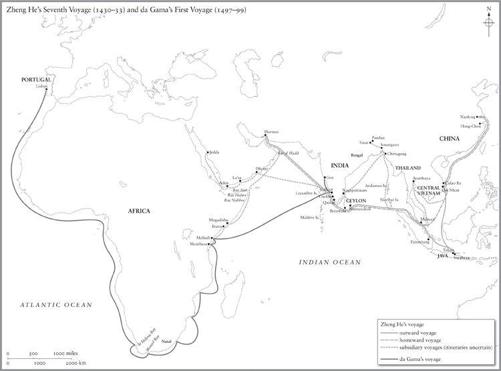

In a series of six epic voyages between 1405 and 1424, Zheng He’s fleet ranged astoundingly far and wide.

*

The Admiral sailed to Thailand, Sumatra, Java and the once-great port of Calicut (today’s Kozhikode in Kerala); to Temasek (later Singapore), Malacca and Ceylon; to Cuttack in Orissa; to Hormuz, Aden and up the Red Sea to Jeddah.

16

Nominally, these voyages were a search for Yongle’s predecessor, who had mysteriously disappeared, as well as for the imperial seal that had vanished with him. (Was Yongle trying to atone for killing his way to the throne, or to cover up for the fact that he had done so?) But to find the lost emperor was not their real motive.

Before his final voyage, Zheng He was ordered ‘on imperial duty to Hormuz and other countries, with ships of different sizes numbering sixty-one … and [to carry] coloured silks … [and] buy hemp-silk’. His officers were also instructed to ‘buy porcelain, iron cauldrons, gifts and ammunition, paper, oil, wax, etc.’.

17

This might seem to suggest a commercial rationale, and certainly the Chinese had goods coveted by Indian Ocean merchants (porcelain, silk and musk), as well as commodities they wished to bring back to China (peppers, pearls, precious stones, ivory and supposedly medicinal rhinoceros horns).

18

In reality, however, the Emperor was not primarily concerned with trade as Adam Smith later understood it. In the words of

a contemporary inscription, the fleet was ‘to go to the [barbarians’] countries and confer presents on them so as to transform them by displaying our power …’. What Yongle wanted in return for these ‘presents’ was for foreign rulers to pay tribute to him the way China’s immediate Asian neighbours did, and thereby to acknowledge his supremacy. And who could refuse to kowtow to an emperor possessed of so mighty a fleet?

19

On three of the voyages, ships from Zheng He’s fleet reached the east coast of Africa. They did not stay long. Envoys from some thirty African rulers were invited aboard to acknowledge the ‘cosmic ascendancy’ of the Ming Emperor. The Sultan of Malindi (in present-day Kenya) sent a delegation with exotic gifts, among them a giraffe. Yongle personally received the animal at the gateway of the imperial palace in Nanjing. The giraffe was hailed as the mythical

qilin

(unicorn) – ‘a symbol of perfect virtue, perfect government and perfect harmony in the empire and the universe’.

20

But then, in 1424, this harmony was shattered. Yongle died – and China’s overseas ambitions were buried with him. Zheng He’s voyages were immediately suspended, and only briefly revived with a final Indian Ocean expedition in 1432–3. The

haijin

decree definitively banned oceanic voyages. From 1500, anyone in China found building a ship with more than two masts was liable to the death penalty; in 1551 it became a crime even to go to sea in such a ship.

21

The records of Zheng He’s journeys were destroyed. Zheng He himself died and was almost certainly buried at sea.

What lay behind this momentous decision? Was it the result of fiscal problems and political wrangles at the imperial court? Was it because the costs of war in Annam (modern-day Vietnam) were proving unexpectedly high?

22

Or was it simply because of Confucian scholars’ suspicion of the ‘odd things’ Zheng He had brought back with him, not least the giraffe? We may never be sure. But the consequences of China’s turn inwards seem clear.

Like the Apollo moon missions, Zheng He’s voyages had been a formidable demonstration of wealth and technological sophistication. Landing a Chinese eunuch on the East African coast in 1416 was in many ways an achievement comparable with landing an American astronaut on the moon in 1969. But by abruptly cancelling oceanic

exploration, Yongle’s successors ensured that the economic benefits of this achievement were negligible.

The same could not be said for the voyages that were about to be undertaken by a very different sailor from a diminutive European kingdom at the other end of the Eurasian landmass.

It was in the Castelo de São Jorge, high in the hills above the windswept harbour of Lisbon, that the newly crowned Portuguese King Manuel put Vasco da Gama in command of four small ships with a big mission. All four vessels could quite easily have fitted inside Zheng He’s treasure ship. Their combined crews were just 170 men. But their mission – ‘to make discoveries and go in search of spices’ – had the potential to tilt the whole world westwards.

The spices in question were the cinnamon, cloves, mace and nutmeg which Europeans could not grow for themselves but which they craved to enhance the taste of their food. For centuries the spice route had run from the Indian Ocean up the Red Sea, or overland through Arabia and Anatolia. By the middle of the fifteenth century its lucrative final leg leading into Europe was tightly controlled by the Turks and the Venetians. The Portuguese realized that if they could find an alternative route, down the west coast of Africa and round the Cape of Good Hope to the Indian Ocean, then this business could be theirs. Another Portuguese mariner, Bartolomeu Dias, had rounded the Cape in 1488, but had been forced by his crew to turn back. Nine years later, it was up to da Gama to go all the way.

King Manuel’s orders tell us something crucially important about the way Western civilization expanded overseas. As we shall see, the West had more than one advantage over the Rest. But the one that really started the ball rolling was surely the fierce competition that drove the Age of Exploration. For Europeans, sailing round Africa was not about exacting symbolic tribute for some high and mighty potentate back home. It was about getting ahead of their rivals, both economically and politically. If da Gama succeeded, then Lisbon

trumped Venice. Maritime exploration, in short, was fifteenth-century Europe’s space race. Or, rather, its spice race.

Da Gama set sail on 8 July 1497. When he and his fellow Portuguese sailors rounded the Cape of Good Hope at the southernmost tip of Africa four months later, they did not ask themselves what exotic animals they should bring back for their King. They wanted to know if they had finally succeeded where others had failed – in finding a new spice route. They wanted trade, not tribute.

In February 1498, fully eighty-two years after Zheng He had landed there, da Gama arrived at Malindi. The Chinese had left little behind aside from some porcelain and DNA – that of twenty Chinese sailors who are said to have been shipwrecked near the island of Pate, to have swum ashore and stayed, marrying African wives and introducing the locals to Chinese styles of basket-weaving and silk production.

23

The Portuguese, by contrast, immediately saw Malindi’s potential as a trading post. Da Gama was especially excited to encounter Indian merchants there and it was almost certainly with assistance from one of them that he was able to catch the monsoon winds to Calicut.

This eagerness to trade was far from being the only difference between the Portuguese and the Chinese. There was a streak of ruthlessness – indeed, of downright brutality – about the men from Lisbon that Zheng He only rarely evinced. When the King of Calicut looked askance at the goods the Portuguese had brought with them from Lisbon, da Gama seized sixteen fishermen as hostages. On his second voyage to India, at the head of fifteen ships, he bombarded Calicut and horribly mutilated the crews of captured vessels. On another occasion, he is said to have locked up the passengers aboard a ship bound for Mecca and set it ablaze.

The Portuguese engaged in exemplary violence because they knew that their opening of a new spice route round the Cape would meet resistance. They evidently believed in getting their retaliation in first. As Afonso de Albuquerque, the second Governor of Portuguese India, proudly reported to his royal master in 1513: ‘At the rumour of our coming the [native] ships all vanished and even the birds ceased to skim over the water.’ Against some foes, to be sure, cannons and cutlasses were ineffective. Half of the men on da Gama’s first expedition did not survive the voyage, not least because their captain attempted

to sail back to Africa against the monsoon wind. Only two of the original four ships made it back to Lisbon. Da Gama himself died of malaria during a third trip to India in 1524; his remains were returned to Europe and are now housed in a fine tomb in the monastery of St Jerome in Lisbon. But other Portuguese explorers sailed on, past India, all the way to China. Once, the Chinese had been able to regard the distant barbarians of Europe with indifference, if not contempt. But now the spice race had brought the barbarians to the gates of the Middle Kingdom itself. And it must be remembered that, though the Portuguese had precious few goods the Chinese wanted, they did bring silver, for which Ming China had an immense demand as coins took the place of paper money and labour service as the principal means of payment.

In 1557 the Portuguese reached Macau, a peninsula on the Pearl River delta. Among the first things they did was to erect a gate – the Porta do Cerco – bearing the inscription: ‘Dread our greatness and respect our virtue.’ By 1586 Macau was an important enough trading outpost to be recognized by the Portuguese Crown as a city: Cidade de Nome de Deus (City of the Name of God). It was the first of many such European commercial enclaves in China. Luís da Camões, author of

The Lusiads

, the epic poem of Portuguese maritime expansion, lived in Macau for a time, after being exiled from Lisbon for assault. How was it, he marvelled, that a kingdom as small as Portugal – with a population less than 1 per cent of China’s – could aspire to dominate the trade of Asia’s vastly more populous empires? And yet on his countrymen sailed, establishing an amazing network of trading posts that stretched like a global necklace from Lisbon, round the coast of Africa, Arabia and India, through the Straits of Malacca, to the spice islands themselves and then on still further, beyond even Macau. ‘Were there more worlds still to discover,’ as da Camões wrote of his countrymen, ‘they would find them too!’

24

The benefits of overseas expansion were not lost on Portugal’s European rivals. Along with Portugal, Spain had been first off the mark, seizing the initiative in the New World (see

Chapter 3

) and also establishing an Asian outpost in the Philippines, whence the Spaniards were able to ship immense quantities of Mexican silver to China.

25

For decades after

the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) had split the world between them, the two Iberian powers could regard their imperial achievements with sublime self-confidence. But the Spaniards’ rebellious and commercially adept Dutch subjects came to appreciate the potential of the new spice route; indeed, by the mid-1600s they had overtaken the Portuguese in terms of both number of ships and tonnage sailing round the Cape. The French also entered the lists.