Civilization: The West and the Rest (5 page)

Clearly, however, one city does not make a civilization. A civilization is the single largest unit of human organization, higher though more amorphous than even an empire. Civilizations are partly a practical response by human populations to their environments – the challenges of feeding, watering, sheltering and defending themselves – but they are also cultural in character; often, though not always, religious; often, though not always, communities of language.

5

They are few, but not far between. Carroll Quigley counted two dozen in the last ten millennia.

6

In the pre-modern world, Adda Bozeman saw just five: the West, India, China, Byzantium and Islam.

7

Matthew Melko made the total twelve, seven of which have vanished (Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Cretan, Classical, Byzantine, Middle American, Andean) and five of which still remain (Chinese, Japanese, Indian, Islamic, Western).

8

Shmuel Eisenstadt counted six by adding Jewish civilization to the club.

9

The interaction of these few civilizations with one another, as much as with their own environments, has been among the most important drivers of historical change.

10

The striking thing about these interactions is that authentic civilizations seem to remain true unto themselves for very long periods, despite outside influences. As Fernand Braudel put it: ‘Civilization is in fact the longest story of all … A civilization … can persist through a series of economies or societies.’

11

If, in the year 1411, you had been able to circumnavigate the globe, you would probably have been most impressed by the quality of life

in Oriental civilizations. The Forbidden City was under construction in Ming Beijing, while work had begun on reopening and improving the Grand Canal; in the Near East, the Ottomans were closing in on Constantinople, which they would finally capture in 1453. The Byzantine Empire was breathing its last. The death of the warlord Timur (Tamerlane) in 1405 had removed the recurrent threat of murderous invading hordes from Central Asia – the antithesis of civilization. For the Yongle Emperor in China and the Ottoman Sultan Murad II, the future was bright.

By contrast, Western Europe in 1411 would have struck you as a miserable backwater, recuperating from the ravages of the Black Death – which had reduced population by as much as half as it swept eastwards between 1347 and 1351 – and still plagued by bad sanitation and seemingly incessant war. In England the leper king Henry IV was on the throne, having successfully overthrown and murdered the ill-starred Richard II. France was in the grip of internecine warfare between the followers of the Duke of Burgundy and those of the assassinated Duke of Orléans. The Anglo-French Hundred Years’ War was just about to resume. The other quarrelsome kingdoms of Western Europe – Aragon, Castile, Navarre, Portugal and Scotland – would have seemed little better. A Muslim still ruled in Granada. The Scottish King, James I, was a prisoner in England, having been captured by English pirates. The most prosperous parts of Europe were in fact the North Italian city-states: Florence, Genoa, Pisa, Siena and Venice. As for fifteenth-century North America, it was an anarchic wilderness compared with the realms of the Aztecs, Mayas and Incas in Central and South America, with their towering temples and skyscraping roads. By the end of your world tour, the notion that the West might come to dominate the Rest for most of the next half-millennium would have come to seem wildly fanciful.

And yet it happened.

For some reason, beginning in the late fifteenth century, the little states of Western Europe, with their bastardized linguistic borrowings from Latin (and a little Greek), their religion derived from the teachings of a Jew from Nazareth and their intellectual debts to Oriental mathematics, astronomy and technology, produced a civilization capable not only of conquering the great Oriental empires and subjugating

Africa, the Americas and Australasia, but also of converting peoples all over the world to the Western way of life – a conversion achieved ultimately more by the word than by the sword.

There are those who dispute that, claiming that all civilizations are in some sense equal, and that the West cannot claim superiority over, say, the East of Eurasia.

12

But such relativism is demonstrably absurd. No previous civilization had ever achieved such dominance as the West achieved over the Rest.

13

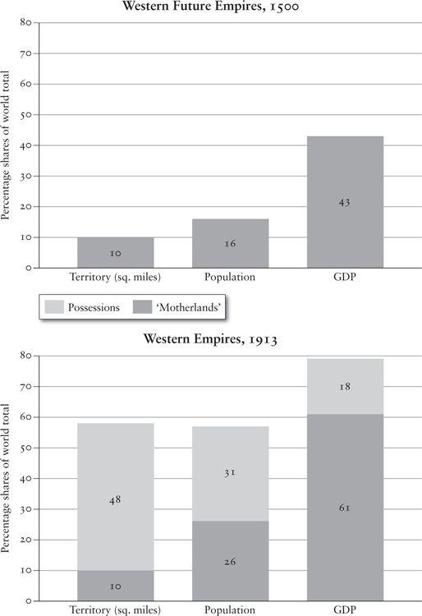

In 1500 the future imperial powers of Europe accounted for about 10 per cent of the world’s land surface and at most 16 per cent of its population. By 1913, eleven Western empires

*

controlled nearly three-fifths of all territory and population and more than three-quarters (a staggering 79 per cent) of global economic output.

14

Average life expectancy in England was nearly twice what it was in India. Higher living standards in the West were also reflected in a better diet, even for agricultural labourers, and taller stature, even for ordinary soldiers and convicts.

15

Civilization, as we have seen, is about cities. By this measure, too, the West had come out on top. In 1500, as far as we can work out, the biggest city in the world was Beijing, with a population of between 600,000 and 700,000. Of the ten largest cities in the world by that time only one – Paris – was European, and its population numbered fewer than 200,000. London had perhaps 50,000 inhabitants. Urbanization rates were also higher in North Africa and South America than in Europe. Yet by 1900 there had been an astonishing reversal. Only one of the world’s ten largest cities at that time was Asian and that was Tokyo. With a population of around 6.5 million, London was the global megalopolis.

16

Nor did Western dominance end with the decline and fall of the European empires. The rise of the United States saw the gap between West and East widen still further. By 1990 the average American was seventy-three times richer than the average Chinese.

17

Moreover, it became clear in the second half of the twentieth century that the only way to close that yawning gap in income was for Eastern societies to follow Japan’s example in adopting some (though not all) of the West’s institutions and modes of operation. As a result, Western civilization became a kind of template for the way the rest of the world aspired to organize itself. Prior to 1945, of course, there was a variety of developmental models – or operating systems, to draw a metaphor from computing – that could be adopted by non-Western societies. But the most attractive were all of European origin: liberal capitalism, national socialism, Soviet communism. The Second World War killed the second in Europe, though it lived on under assumed names in many developing countries. The collapse of the Soviet empire between 1989 and 1991 killed the third.

To be sure, there has been much talk in the wake of the global financial crisis about alternative Asian economic models. But not even the most ardent cultural relativist is recommending a return to the institutions of the Ming dynasty or the Mughals. The current debate between the proponents of free markets and those of state intervention is, at root, a debate between identifiably Western schools of thought: the followers of Adam Smith and those of John Maynard Keynes, with a few die-hard devotees of Karl Marx still plugging away. The birthplaces of all three speak for themselves: Kirkcaldy, Cambridge, Trier. In practice, most of the world is now integrated into a Western economic system in which, as Smith recommended, the market sets most of the prices and determines the flow of trade and division of labour, but government plays a role closer to the one envisaged by Keynes, intervening to try to smooth the business cycle and reduce income inequality.

As for non-economic institutions, there is no debate worth having. All over the world, universities are converging on Western norms. The same is true of the way medical science is organized, from rarefied research all the way through to front-line healthcare. Most people now accept the great scientific truths revealed by Newton, Darwin and Einstein and, even if they do not, they still reach eagerly for the products of Western pharmacology at the first symptom of influenza or bronchitis. Only a few societies continue to resist the encroachment of Western patterns of marketing and consumption, as well as the Western lifestyle itself. More and more human beings eat a Western diet, wear Western clothes and live in Western housing. Even the peculiarly Western way of work – five or six days a week from 9 until 5,

with two or three weeks of holiday – is becoming a kind of universal standard. Meanwhile, the religion that Western missionaries sought to export to the rest of the world is followed by a third of mankind – as well as making remarkable gains in the world’s most populous country. Even the atheism pioneered in the West is making impressive headway.

With every passing year, more and more human beings shop like us, study like us, stay healthy (or unhealthy) like us and pray (or don’t pray) like us. Burgers, Bunsen burners, Band-Aids, baseball caps and Bibles: you cannot easily get away from them, wherever you may go. Only in the realm of political institutions does there remain significant global diversity, with a wide range of governments around the world resisting the idea of the rule of law, with its protection of individual rights, as the foundation for meaningful representative government. It is as much as a political ideology as a religion that a militant Islam seeks to resist the advance of the late twentieth-century Western norms of gender equality and sexual freedom.

18

So it is not ‘Eurocentrism’ or (anti-)‘Orientalism’ to say that the rise of Western civilization is the single most important historical phenomenon of the second half of the second millennium after Christ. It is a statement of the obvious. The challenge is to explain how it happened. What was it about the civilization of Western Europe after the fifteenth century that allowed it to trump the outwardly superior empires of the Orient? Clearly, it was something more than the beauty of the Sistine Chapel.

The facile, if not tautological, answer to the question is that the West dominated the Rest because of imperialism.

19

There are still many people today who can work themselves up into a state of high moral indignation over the misdeeds of the European empires. Misdeeds there certainly were, and they are not absent from these pages. It is also clear that different forms of colonization – settlement versus extraction – had very different long-term impacts.

20

But empire is not a historically sufficient explanation of Western predominance. There were empires long before the imperialism denounced by the Marxist-Leninists. Indeed, the sixteenth century saw a number of Asian empires increase significantly in their power and extent. Meanwhile, after the failure of Charles V’s project of a grand Habsburg empire

stretching from Spain through the Low Countries to Germany, Europe grew more fragmented than ever. The Reformation unleashed more than a century of European wars of religion.

A sixteenth-century traveller could hardly have failed to notice the contrast. In addition to covering Anatolia, Egypt, Arabia, Mesopotamia and Yemen, the Ottoman Empire under Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–66) extended into the Balkans and Hungary, menacing the gates of Vienna in 1529. Further east, the Safavid Empire under Abbas I (1587–1629) stretched all the way from Isfahan and Tabriz to Kandahar, while Northern India from Delhi to Bengal was ruled by the mighty Mughal Emperor Akbar (1556–1605). Ming China, too, seemed serene and secure behind the Great Wall. Few European visitors to the court of the Wanli Emperor (1572–1620) can have anticipated the fall of his dynasty less than three decades after his death. Writing from Istanbul in the late 1550s, the Flemish diplomat Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq – the man who transplanted tulips from Turkey to the Netherlands – nervously compared Europe’s fractured state with the ‘vast wealth’ of the Ottoman Empire.

True, the sixteenth century was a time of hectic European activity overseas. But to the great Oriental empires the Portuguese and Dutch seafarers seemed the very opposite of bearers of civilization; they were merely the latest barbarians to menace the Middle Kingdom, if anything more loathsome – and certainly more malodorous – than the pirates of Japan. And what else attracted Europeans to Asia but the superior quality of Indian textiles and Chinese porcelain?

As late as 1683, an Ottoman army could march to the gates of Vienna – the capital of the Habsburg Empire – and demand that the city’s population surrender and convert to Islam. It was only after the raising of the siege that Christendom could begin slowly rolling back Ottoman power in Central and Eastern Europe through the Balkans towards the Bosphorus, and it took many years before any European empire could match the achievements of Oriental imperialism. The ‘great divergence’ between the West and the Rest was even slower to materialize elsewhere. The material gap between North and South America was not firmly established until well into the nineteenth century, and most of Africa was not subjugated by Europeans beyond a few coastal strips until the early twentieth.