Civilization: The West and the Rest (25 page)

Nevertheless, there were important differences between the forms of slavery that evolved in the New World. Slavery had been an integral part of the Mediterranean economy since ancient times and had revived in the era of the Crusades, whereas in England it had essentially died out. The status of villeinage had ceased to feature in the common law at a time when the Portuguese were opening a new sea route from the West African slave markets to the Mediterranean and establishing the first Atlantic sugar plantations, first in the Madeiras (1455) and then on São Tomé in the Gulf of Guinea (1500).

76

The first African slaves arrived in Brazil as early as 1538; there were none in the future United States before 1619, when 350 arrived at Jamestown, having been taken as booty from a Spanish ship bound for Veracruz.

77

There were no sugar plantations in North America; and these – the

engenhos

of Bahia and Pernambuco – were undoubtedly the places where working conditions for slaves were harshest, because of the peculiarly labour-intensive characteristics of pre-industrial sugar cultivation.

*

The goldmines of southern Brazil (such as Minas Gerais) were not much better, nor the coffee plantations of the early nineteenth century. Many more Africans were shipped to Brazil than to the southern United States. Indeed, Brazil swiftly outstripped the Caribbean as the world’s principal centre of sugar production, producing nearly 16,000 tons a year as early as 1600. (It was only later that production in Santo Domingo and Cuba reached comparable levels.)

78

Although the economy diversified over time from sugar production to mining, coffee growing and basic manufacturing, slaves

continued to be imported in preference to free migrants, and slavery was the normal form of labour in almost every economic sector.

79

So important was slavery to Brazil that by 1825 people of African origin or descent accounted for 56 per cent of the population, compared with 22 per cent in Spanish America and 17 per cent in North America. Long after the abolition of the slave trade and slavery itself in the English-speaking world, the Brazilians continued with both, importing more than a million new slaves between 1808 and 1888, despite an Anglo-Brazilian treaty of 1826 that was supposed to end the trade. By the 1850s, when British naval interventions began seriously to disrupt the transatlantic traffic, the Brazilian slave population was double what it had been in 1793.

The lot of slaves in pre-revolutionary Latin America was not wholly wretched. Royal and religious authority could and did intervene to mitigate the condition of the slaves, just as it could limit other private property rights. The Roman Catholic presumption was that slavery was at best a necessary evil; it could not alter the fact that Africans had souls. Slaves on Latin American plantations could more easily secure manumission than those on Virginian tobacco farms. In Bahia slaves themselves purchased half of all manumissions.

80

By 1872 three-quarters of blacks and mulattos in Brazil were free.

81

In Cuba and Mexico a slave could even have his price declared and buy his freedom in instalments.

82

Brazilian slaves were also said to enjoy more days off (thirty-five saints’ days as well as every Sunday) than their counterparts in the British West Indies.

83

Beginning in Brazil, it became the norm in Latin America for slaves to have their own plots of land.

Not too rosy a picture should be painted, to be sure. When exports were booming, some Brazilian sugar plantations operated twenty hours a day, seven days a week, and slaves were quite literally worked to death. It was a Brazilian plantation-owner who declared that ‘when he bought a slave, it was with the intention of using him for a year, longer than which few could survive, but that he got enough work out of him not only to repay this initial investment, but even to show a good profit’.

84

As in the Caribbean, planters lived in constant fear of slave revolts and relied on exemplary brutality to maintain discipline. A common punishment on some Brazilian plantations was the

novenas

, a flogging over nine consecutive nights, during which the victim’s

wounds were rubbed with salt and urine.

85

In eighteenth-century Minas Gerais it was not unknown for the severed heads of fugitive slaves to be displayed at the roadside. Small wonder average life expectancy for a Brazilian slave was just twenty-three as late as the 1850s; a slave had to last only five years for his owner to earn twice his initial investment.

86

On the other hand, Brazilian slaves at least enjoyed the right to marry, which was denied to slaves under British (and Dutch) law. And the tendency of both the Portuguese and the Spanish slave codes was to become less draconian over time.

In North America slave-owners felt empowered to treat all their ‘chattels’ as they saw fit, regardless of whether they were human beings or plots of land. As the population of slaves grew – reaching a peak of nearly a third of the British American population by 1760 – the authorities drew an ever sharper distinction between white indentured labourers, whose period of servitude was usually set at five or six years, and black slaves, who were obliged to serve for their whole lives. Legislation enacted in Maryland in 1663 was unambiguous: ‘All Negroes or other slaves in the province … shall serve

durante vitae

; and all children born of any Negro or other slave shall be slaves as their fathers were.’

87

And North American slavery became stricter over time. A Virginian law of 1669 declared it no felony if a master killed his slave. A South Carolina law of 1726 explicitly stated that slaves were ‘chattels’ (later ‘chattels personal’). Corporal punishment was not only sanctioned but codified.

88

It reached the point that fugitive slaves from Carolina began to cross the border into Spanish Florida, where the Governor allowed them to establish an autonomous settlement, provided they converted to Catholicism.

89

This was a remarkable development, given that – as we have seen – chattel slavery had died out in England centuries before, illustrating how European institutions were perfectly capable of mutating on American soil. A Virginian magistrate neatly captured the tension at the heart of the ‘peculiar institution’ when he declared: ‘Slaves are not only property, but they are rational beings, and entitled to the humanity of the Court, when it can be exercised

without invading the rights of property

.’

90

Slave-traders laid themselves open to attack by abolitionists only when they overstepped a very elevated threshold, as the captain of the Liverpool ship the

Zong

did when, in 1782, he

threw 133 slaves overboard, alive and chained, because of a shortage of water on board. Significantly, he was first prosecuted for insurance fraud before Olaudah Equiano alerted the abolitionist Granville Sharp to the real nature of the crime that had been committed.

91

An especially striking difference between North and South was the North American taboo against racial interbreeding – ‘miscegenation’, as it was once known. Latin America accepted from early on the reality of interracial unions, classifying their various products (mestizos, the offspring of Spanish men and Indian women; mulattos, born of unions of creoles and blacks; and zambos, the children of Indians and blacks) in increasingly elaborate hierarchies. Pizarro himself had taken an Inca wife, Inés Huayllas Yupanqui, who bore him a daughter Doña Francisca.

92

By 1811 these various ‘half-breeds’ – the English term was intended to be pejorative – constituted more than a third of the population of Spanish America, a share equal to the indigenous population, and more than creoles of pure Hispanic origin, who accounted for less than a fifth. In eighteenth-century Brazil mulattos accounted for just 6 per cent of the predominantly African plantation workforce, but a fifth of the more skilled artisanal and managerial positions; they were the subaltern class of the Portuguese Empire.

In the United States, by contrast, elaborate efforts were made to prohibit (or at least deny the legitimacy of) such unions. This was partly a practical consequence of another difference. When the British emigrated to America, they often took their womenfolk with them. When Spanish and Portuguese men crossed the Atlantic, they generally travelled alone. For example, of the 15,000 names recorded in the ‘Catálogo de Pasajeros a Indias’, a list of Spanish passengers who embarked for the New World between 1509 and 1559, only 10 per cent were female. The results were not difficult to foresee. Scientists led by Andrés Ruiz-Linares have studied individual mitochondrial DNA samples from thirteen Latin American mestizo populations in seven countries from Chile to Mexico. The results show clearly that, right across Latin America, European men took indigenous and African women as mates, not the other way round.

93

Case studies of places like Medellín in Colombia – where the population is often regarded as ‘purely’ Hispanic – support this finding. In one sample, Y-chromosome lineages (inherited from the father) were found to be

around 94 per cent European, 5 per cent African and just 1 per cent Amerindian, whereas mitochondrial DNA lineages (inherited from the mother) were 90 per cent Amerindian, 8 per cent African and 2 per cent European.

94

It was not that miscegenation did not happen in North America. It did. Thomas Jefferson is only the most famous American to have fathered children by one of his slaves. There were approximately 60,000 mulattos in British America by the end of the colonial era. Today between a fifth and a quarter of the DNA of most African-Americans in the United States can be traced back to Europeans. But the model that took root in the colonial period was essentially binary. An individual with even a ‘drop’ of African-American blood – in Virginia, a single black grandparent – was categorized as black no matter how pale her skin or Caucasian her physiognomy. Interracial marriage was treated as a punishable offence in Virginia from as early

as 1630 and was legally prohibited in 1662; the colony of Maryland had passed similar legislation a year earlier. Such laws were enacted by five other North American colonies. In the century after the foundation of the United States, no fewer than thirty-eight states banned interracial marriages. As late as 1915, twenty-eight states retained such statutes; ten of them had gone so far as to make the prohibition on miscegenation constitutional. There was even an attempt, in December 1912, to amend the US constitution so as to prohibit miscegenation ‘for ever’.

95

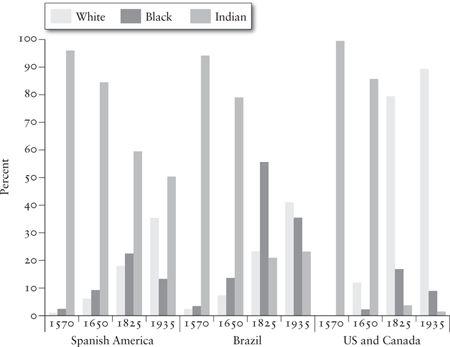

The Racial Structure of the New World, 1570–1935

NOTE

: Data on mixed-race populations unavailable.

It made a big difference, then, where African slaves went. Those bound for Latin America ended up in something of a racial melting pot where a male slave had a reasonable chance of gaining his freedom if he survived the first few years of hard labour and a female slave had a non-trivial probability of producing a child of mixed race. Those consigned to the United States entered a society where the distinction between white and black was much more strictly defined and upheld.

As we have seen, it was John Locke who had made private property the foundation of political life in Carolina. But it was not only landed property he had in mind. In article 110 of his ‘Fundamental Constitutions’, he had stated clearly: ‘Every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves, of what opinion or religion soever.’ For Locke, the ownership of human beings was as much a part of the colonial project as the ownership of land. And these human beings would be neither landowners nor voters. Subsequent law-makers strove to maintain this distinction. Section X of the South Carolina Slave Code of 1740 authorized a white person to detain and examine any slave found outside a house or plantation who was not accompanied by a white person. Section XXXVI prohibited slaves from leaving their plantation, especially on Saturday nights, Sundays and holidays. Slaves who violated the law could be subjected to a ‘moderate whipping’. Section XLV prohibited white persons from teaching slaves to read and write.

The profound effects of such laws are discernible in parts of the United States even today. The Gullah Coast stretches from Sandy Island, South Carolina, to Amelia Island, Florida. People here have their own distinctive patois, cuisine and musical style.

96

Some anthropologists

believe that ‘Gullah’ is a corruption of ‘Angola’, where the inhabitants’ ancestors may have come from. It is possible. Beginning in the mid-seventeenth century, a very high proportion of all the slaves transported to the Americas – perhaps as many as 44 per cent – came from the part of Africa contemporaries called Angola (the modern country plus the region between the Cameroons and the north bank of the Congo River).

97

A third of the slaves who passed through Charleston were from Angola.

98

Most of these were taken from the Mbundu people of the Ndongo kingdom, whose ruler, the

ngola

, gives the modern country its name. They ended up scattered all over the Americas, from Brazil to the Bahamas to the Carolinas.