Civilization: The West and the Rest (27 page)

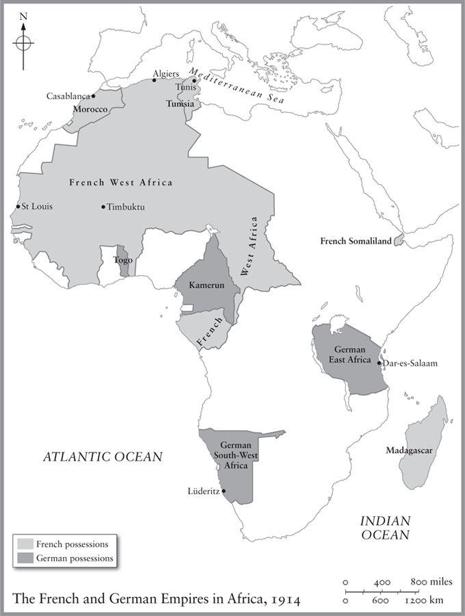

By 1913 Western empires dominated the world. Eleven motherlands covering just 10 per cent of the world’s land surface governed more than half the world. An estimated 57 per cent of the world’s population lived in these empires, which accounted for close to four-fifths of global economic output. Even at the time, their conduct aroused bitter criticism. Indeed, the word ‘imperialism’ is a term of abuse that caught on with nationalists, liberals and socialists alike. These critics rained coruscating ridicule on the claim that the empires were exporting civilization. Asked what he thought of Western civilization, the Indian nationalist leader Mahatma Gandhi is said to have replied wittily that he thought it would be a good idea. In

Hind Swaraj

(‘Indian Home Rule’), published in 1908, Gandhi went so far as to call Western civilization ‘a disease’ and ‘a bane’.

2

Mark Twain, America’s leading anti-imperialist, preferred irony. ‘To such as believe’, he wrote in 1897, ‘that the quaint product called French civilization would be an improvement upon the civilization of New Guinea and the like, the snatching of Madagascar and the laying on of French civilization there will be fully justified.’

3

The Bolshevik leader Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was also being ironic when he called imperialism ‘the highest stage of capitalism’, the result of monopolistic banks struggling ‘for the sources of raw materials, for the export of capital, for spheres of influence, i.e., for spheres for profitable deals, concessions, monopoly profits and so on’. In fact he regarded imperialism as ‘parasitic’, ‘decaying’ and ‘moribund capitalism’.

4

These are views of the

age of empire still shared by many people today. Moreover, it is a truth almost universally acknowledged in the schools and colleges of the Western world that imperialism is the root cause of nearly every modern problem, from conflict in the Middle East to poverty in sub-Saharan Africa – a convenient alibi for rapacious dictators like Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe.

Yet it is becoming less and less easy to blame the contemporary plight of the ‘bottom billion’ – the people living in the world’s poorest countries – on the colonialism of the past.

5

There were and remain serious environmental and geographical obstacles to Africa’s economic development. Independent rulers, with few exceptions, did not perform better than colonial rulers before or after independence; most did much worse. And today, an altogether different Western civilizing mission – the mission of the governmental and non-governmental aid agencies – has clearly achieved much less than was once hoped, despite the transfer of immense sums in the form of aid.

6

For all the best efforts of Ivy League economists and Irish rock stars, Africa remains the poor relation of the continents, reliant either on Western alms or on the extraction of its raw materials. There are, it is true, glimmers of improvement, not least the effects of cheap mobile telephony, which (for example) is providing Africans for the first time with efficient and low-cost banking services. There is also a real possibility that clean water could be made far more widely available than it currently is.

*

Nevertheless the barriers to growth remain daunting, not least the abysmal governance that plagues so many African states, symbolized by the grotesque statue that now towers over Dakar, representing a gigantic Senegalese couple in the worst socialist-realist style. (It was built by a North Korean state enterprise.) The advent of China as a major investor in Africa is doing little to address that problem. On the contrary, the Chinese are happy to trade infrastructure investment for access to Africa’s mineral wealth, regardless of whether they are doing business with military dictators, corrupt kleptocrats or senile autocrats

(or all three). Just when Western government and non-government agencies are at least beginning to demand improvements in African governance as conditions for aid, they find themselves undercut by a nascent Chinese empire.

This coincidence of foreign altruism and foreign exploitation is nothing new in African history. In the nineteenth century, as we have seen, Europeans came to Africa with a mixed bag of motives. Some were in it for the money, others for the glory. Some came to invest, others to rob. Some came to uplift souls, others to put down roots. Nearly all, however, were certain – as certain as today’s aid agencies – that the benefits of Western civilization could and should be conferred on the ‘Dark Continent’.

*

Before we rush to condemn the Western empires as evil and exploitative – capable only of behaviour that was the very reverse of civilized – we need to understand that there was more than a little substance to their claim that they were on a civilizing mission.

Take the case of the West’s most remarkable killer application – the one that, far from being a killer, had the power to double human life expectancy: modern medicine. The ascetic holy man Gandhi was scornful of Western civilization’s ‘army of doctors’. In an interview in London in 1931 he cited the ‘conquest of disease’ as one of the purely ‘material’ yardsticks by which Western civilization measured progress.

7

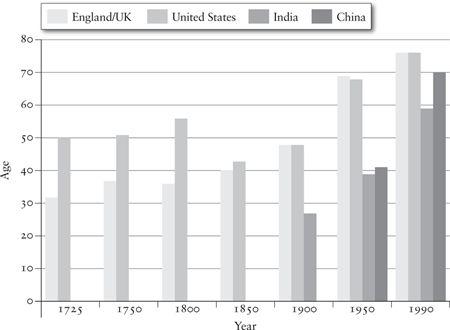

To the countless millions of people whose lives have been lengthened by Western medicine, however, the choice between spiritual purity and staying alive was not difficult to make. Average global life expectancy at birth in around 1800 was just 28.5 years. Two centuries later, in 2001, it had more than doubled to 66.6 years. The improvement was not confined to the imperial metropoles. Those historians who habitually confuse famines or civil wars with genocides and gulags, in a wilful attempt to represent colonial officials as morally equivalent to Nazis or Stalinists, would do well to ponder the measurable impact of Western medicine on life expectancy in the colonial and post-colonial world.

Life Expectancy at Birth: England, the United States, India and China, 1725–1990

The timing of the ‘health transition’ – the beginning of sustained improvements in life expectancy – is quite clear. In Western Europe it came between the 1770s and the 1890s, beginning first in Denmark, with Spain bringing up the rear. By the eve of the First World War typhoid and cholera had effectively been eliminated in Europe as a result of improvements in public health and sanitation, while diphtheria and tetanus were controlled by vaccine. In the twenty-three modern Asian countries for which data are available, with one exception, the health transition came between the 1890s and the 1950s. In Africa it came between the 1920s and the 1950s, with just two exceptions out of forty-three countries. In nearly all Asian and African countries, then, life expectancy began to improve

before

the end of European colonial rule. Indeed, the rate of improvement in Africa has declined since independence, especially but not exclusively because of the HIV-AIDS epidemic. It is also noteworthy that Latin American countries did not fare any better, despite enjoying political independence from the early 1800s.

8

The timing of the improvement in life

expectancy is especially striking as much of it predated the introduction of antibiotics (not least streptomycin as a cure for tuberculosis), the insecticide DDT and vaccines other than the simple ones for smallpox and yellow fever invented in the imperial era (see below). The evidence points to sustained improvements in public health along a broad front, reducing mortality due to faecal disease, malaria and even tuberculosis. That was certainly the experience of one British colony, Jamaica, and the story was probably similar in others like Ceylon, Egypt, Kenya, Rhodesia, Trinidad and Uganda, which experienced more or less simultaneous improvements.

9

As we shall see, the same holds true for France’s colonies. It turns out that Africa’s uniquely life-threatening repertoire of tropical diseases elicited a sustained effort on the part of the West’s scientists and health officials that would not have been forthcoming in the absence of imperialism. Here the Irish playwright and wit George Bernard Shaw provides the perfect answer to Gandhi:

For a century past civilization has been cleaning away the conditions which favour bacterial fevers. Typhus, once rife, has vanished: plague and cholera have been stopped at our frontiers by a sanitary blockade … The dangers of infection and the way to avoid it are better understood than they used to be … Nowadays the troubles of consumptive patients are greatly increased by the growing disposition to treat them as lepers … But the scare of infection, though it sets even doctors talking as if the only really scientific thing to do with a fever patient is to throw him into the nearest ditch and pump carbolic acid on him from a safe distance until he is ready to be cremated on the spot, has led to much greater care and cleanliness. And the net result has been a series of victories over disease.

10

These victories were not confined to the imperialists but also benefited their colonial subjects.

The twist in the tale is that even the medical science of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had its dark side. The fight against pathogens coincided with a pseudo-scientific fight again the illusory threat of racial degeneration. Finally, in 1914, a war between the rival Western empires, billed as ‘the great war for civiliza

tion’, would reveal that Africa was not, after all, the world’s darkest continent.

Most empires proclaim their own irenic intention to bring civilization to backward countries. But few in history were fonder of the phrase ‘civilizing mission’ than the French. To understand why, it is necessary first to appreciate the profound difference between the French and American revolutions. The first man to understand this difference was the Whig parliamentarian Edmund Burke, the greatest political thinker to emerge from the Pale of Protestant Settlement in Southern Ireland. Burke had supported the American Revolution, sympathizing strongly with the colonists’ argument that they were being taxed without representation, and correctly discerning that Lord North’s ministry was bungling the original crisis over taxation in Massachusetts. Burke’s reaction to the outbreak of revolution in France was diametrically opposite. ‘Am [I] seriously to felicitate a madman’, he wrote in his

Reflections on the Revolution in France

, ‘who has escaped from the protecting restraint and wholesome darkness of his cell, on his restoration to the enjoyment of light and liberty? Am I to congratulate a highwayman and murderer who has broke prison upon the recovery of his natural rights?’

11

Burke divined the French Revolution’s violent character at an amazingly early stage. Those words were published 0n 1 November 1790.

The political chain reaction that began in 1789 was the result of a chronic fiscal crisis that had been rendered acute by French intervention in the American Revolution. Since the traumatic financial crisis of 1719–20 – the Mississippi Bubble – the French fiscal system had lagged woefully behind the English. There was no central note-issuing bank. There was no liquid bond market where government debt could be bought and sold. The tax system had in large measure been privatized. Instead of selling bonds, the French Crown sold offices, creating a bloated public payroll of parasites. A succession of able ministers – Charles de Calonne, Loménie de Brienne and Jacques Necker – tried and failed to reform the system. The easy way out of the mess would have been for Louis XVI to default on the monarchy’s debts, which took a bewildering variety of different forms and cost almost twice

what the British government was paying on its standardized bonds.

12

Instead, the King sought consensus. An Assembly of Notables went nowhere. The lawyers of the

parlements

only made trouble. Finally, in August 1788, Louis was persuaded to summon the Estates General, a body that had not met since 1614. He should have foreseen that a seventeenth-century institution would give him a seventeenth-century crisis.