Criminal Poisoning: Investigational Guide for Law Enforcement, Toxicologists, Forensic Scientists, and Attorneys (17 page)

Authors: John H. Trestrail

5.8. REFERENCES

Adelson L: Murder by poison. In:

The Pathology of Homicide.

Charles C Thomas, Springfield, IL, 1974, pp. 725–875.

Department of the Army:

Crimes Involving Poison

. Department of the Army Technical Bulletin TB PMG 21. Department of the Army, Washington, DC, 1967, pp. 11–13.

Sparrow G:

Women Who Murder.

Abelard-Schuman, New York, 1970, p. 156.

Crime Scene Investigation

81

5.9. SUGGESTED READING

Thorwald J:

The Century of the Detective.

Harcourt, Brace & World, New York, 1964.

Thorwald J:

Crime and Science: The New Frontier in Criminology.

Harcourt, Brace & World, New York, 1966.

The Forensic Autopsy

83

The Forensic Autopsy

“Revolted by the odious crime of homicide, the chemist’s aim is to perfect the means of establishing proof of poisoning so that the heinous crime will be brought to light and proved to the magistrate who must punish the criminal.”—M. J. B. Orfila, 1817

6.1. THE AUTOPSY

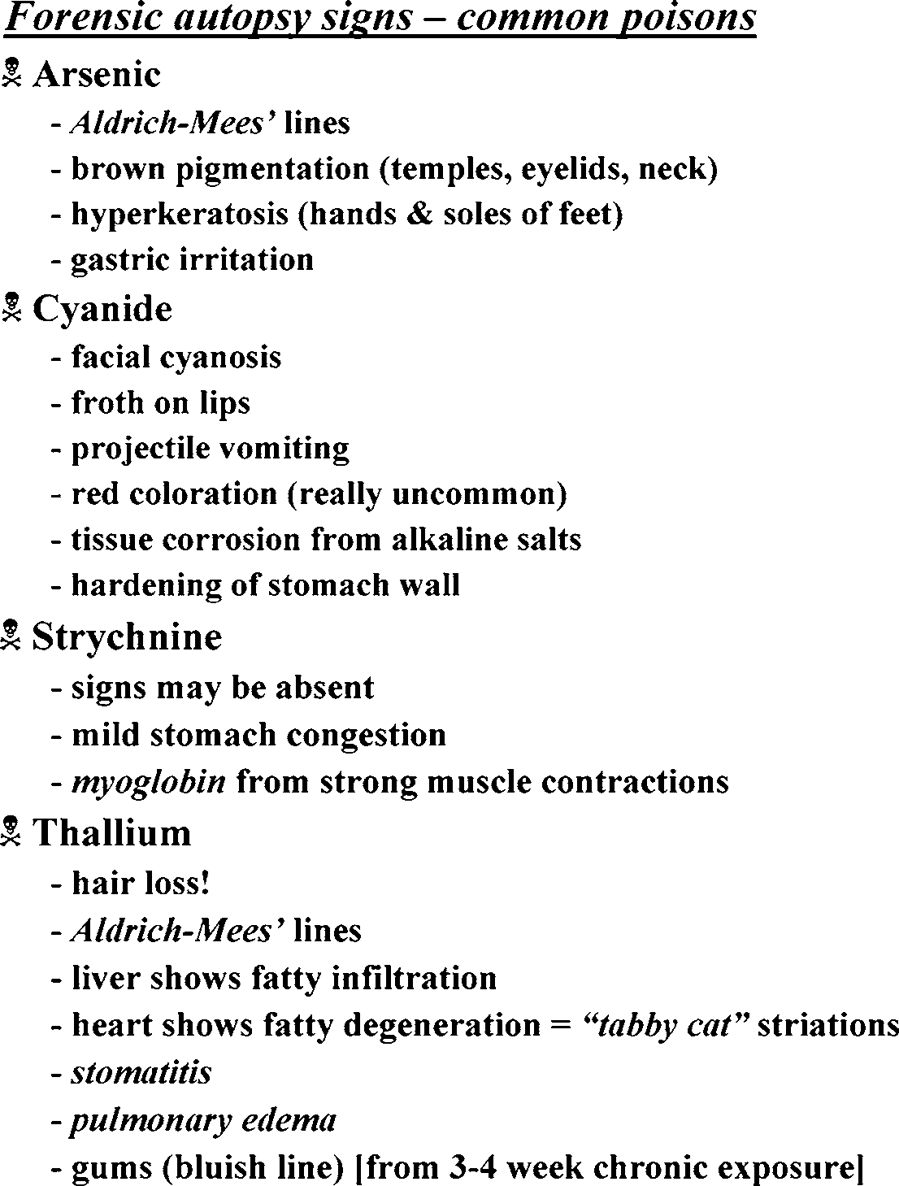

During an autopsy, the forensic pathologist looks for certain clues that might indicate that a poison could have been involved in the death. These clues could include irritated tissues (from caustic and corrosive compounds); characteristic odors, such as the almond-like odor of cyanide; or Aldrich-Mees lines (white bands on the nails that indicate chronic exposure to heavy metals such as arsenic) (

see

Fig. 6-1

).

6.2. POSTMORTEM REDISTRIBUTION—“NECROKINETICS”

The pathologist also reviews the results of any toxicological screens, to determine whether they are consistent with his or her pathological findings.

Certain cautions in the interpretation of the analytical toxicology results should be observed.

The concentrations of substances revealed by an analytical test will vary, depending on the site of origin of the specimen as well as the length of time that has passed since the initial exposure. The reliability of any postmortem specimen is directly related to the conditions associated with the collection of that specimen and the storage environment. It has become increasingly clear that the blood concentration of many drugs is definitely dependent on the site of collection, and that blood concentration may be significantly higher, or From: Forensic Science and Medicine: Criminal Poisoning, Second Edition By: J. H. Trestrail, III © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ

83

84

Criminal Poisoning

Figure 6-1

sometimes lower, than at the time of death. If the pathologist removes blood merely from the left side of the heart or, worse yet, obtains a sample from the chest or abdominal cavity of the victim, this can yield results that may lead the investigator far astray from the actual meaningful and more accurate analytical results. Unfortunately, the ability to interpret the results of toxicological analyses has not kept pace with the great advancements that have been made in the detection limits of analytical instrumentation.

It is unfortunate that the literature available on postmortem levels in fatal intoxications typically consists only of case reports. It would be of extreme value to forensic scientists if an international database listing chemical subThe Forensic Autopsy 85

stances that have been detected in bodies in relation to the time interval since death existed. This database should list the name of the substance, the type of specimen, the time interval since death that the specimen was obtained as well as analyzed, the determined level, and the type of analytical technique utilized. In other words, how long after death was it possible to prove the presence of a substance in the body? This information has major implications when considering the possible value of exhuming the body of a victim thought to have been poisoned.

It is well known that chemical substances redistribute in the body, a phenomenon often referred to as “anatomical site concentration” or “postmortem redistribution.” This phenomenon could also well be called “necrokinetics,” or the movement of substances after death has occurred.

Many studies have shown that the concentrations of certain drugs, such as propoxyphene and the tricyclic antidepressants, are increased in heart blood postmortem. Some researchers have proposed that drug concentrations obtained from liver specimens are much better indicators of toxicity (Hilberg, Rogde, & Morland, 1999; Jones & Pounder, 1987; Langford & Pounder, 1997).

Factors that can alter the movement of substances, and, therefore, their final concentrations in an analytical specimen, include acid-base changes in the body after death and the volume of distribution (

Vd

) of the substance in question.

Volume of distribution

is defined as that volume of fluid into which a drug appears to distribute to a concentration equal to that in plasma. Drugs with a low

Vd

will become less ionized as the pH (acidity) in the body decreases (i.e., becomes more acidic), and, therefore, their solubility in the surrounding tissues will increase. Examples of drugs that will shift with this change in acidity include salicylates, theophylline, and phenobarbital.

The ideal toxicological sample would be a peripheral sample obtained from a blood vessel that had been ligated shortly after death. Unfortunately, this ideal is seldom obtained in the case of homicidal poisoning.

6.3. ANALYTICAL GUIDELINES

The following guidelines must be kept in mind when carrying out a toxicological analysis: • Postmortem concentrations are absolutely site dependent.

• Samples taken from the same site in the body will show different concentrations postmortem, depending on the time the sample was obtained.

• From a single postmortem measurement, no realistic calculation of the absorbed dose to create that level can really be made.

86

Criminal Poisoning

• When obtaining samples for analysis, a clean instrument must be used for each specimen, to avoid possible cross-contamination of specimens and erroneous results.

• Both the death scene investigator and the pathologist can provide crucial information to the toxicological analyst.

• Absolute chain of custody must be maintained on all specimens throughout the process from their procurement through their toxicological analyses.

6.4. REFERENCES

Hilberg T, Rogde S, Morland J: Postmortem drug redistribution—human cases related to results in experimental animals.

J Forensic Sci

1999;44(1):3–9.

Jones GR, Pounder DJ: Site dependence of drug concentrations in postmortem blood—a case study.

J Anal Toxicol

1987;11:187–191.

Langford AM, Pounder DJ: Possible markers for postmortem drug redistribution.

J

Forensic Sci

1997;42(1):88–92.

Orfila MJB: A General System of Toxicology, or a Treatise in Poisons Found in the Mineral, Vegetable and Animal Kingdoms Considered in their Relations with Physiology, Pathology and Medical Jurisprudence. Carey & Son, Philadelphia, PA, 1817.

6.5. SUGGESTED READING

Druid H, Holmgren P: A compilation of fatal and control concentrations of drugs in postmortem femoral blood.

J Forensic Sci

1997;42(1):79–87.

Imwinkelried EJ: Forensic science: toxicological procedures to identify poisons.

Crim Law Bull

1994;30:172–179.

Moriya F, Hashimoto Y: Redistribution of basic drugs into cardiac blood from surrounding tissues during early-states postmortem.

J Forensic Sci

1999;44(1):10–16.

Pounder DJ, Jones GR: Postmortem drug redistribution—a toxicological nightmare.

Forensic Sci Int

1990;45:253–263.

Repetto MR, Repetto M: Habitual, toxic, and lethal concentrations of 103 drugs of abuse in humans.

Clin Toxicol

1997;35(1):1–9.

Repetto MR, Repetto M: Therapeutic, toxic, and lethal concentrations in human fluids of 90 drugs affecting the cardiovascular and hematopoietic systems.

Clin Toxicol 1997;35(4):345–351.

Repetto MR, Repetto M: Therapeutic, toxic and lethal concentrations of 73 drugs affecting respiratory system in human fluids.

Clin Toxicol

1998;36(4):287–293.

Repetto MR, Repetto M: Concentrations in human fluids: 101 drugs affecting the diges-tive system and metabolism.

Clin Toxicol

1999;37(1):1–8.

Watson WA: The toxicokinetics of poisoning and drug overdose.

Am Assoc Clin Chem 1991;12(8):7–12.

Proving Poisoning

87

Proving Poisoning

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”—Sherlock Holmes, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Let us begin our discussion of the proof that a murder by poison has been committed by discussing the proper utilization of the services of an analytical toxicology laboratory, because it will play a key role in the detection of the crime.

First of all, a “shotgun” approach to detection will most likely not be successful. One cannot hand analytical toxicology personnel a specimen and say that poisoning is suspected and ask them to prove that a poisonous compound is present in the specimen. The analysts need some guidelines as to what compounds are suspected. These guidelines come from the criminal investigator’s analysis of the death scene, as well as the pathological findings that derived from the autopsy. The key here is that once there has been a death, a qualified medical examiner should be called in to the case immediately.

The investigator should also be aware that the concentration of compounds may differ depending on the site of origin of a blood specimen, in that cardiac (heart) blood may differ from peripheral (away from the central portion) blood in the quantitative analyses.

From: Forensic Science and Medicine: Criminal Poisoning, Second Edition By: J. H. Trestrail, III © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ

87

88

Criminal Poisoning

7.1. KEY ELEMENTS TO BE PROVEN

The following elements are key to proving that someone has been poisoned:

•

Discovery:

This consists of legally proving that a crime was committed, and dem-onstrating beyond

reasonable doubt

that death was caused by poison, administered with malicious or evil intent to the deceased. Never forget the importance of the chain of evidence on all investigational specimens.

•

Motive

: This is critical because the investigator must clearly establish the instigating force behind the action. Why would anyone want to carry out such an act on the victim? This is where the close study of the victim (victimology) becomes central to the case.

•

Intent

: This constitutes the purpose or aim that an individual would have in commission of the act. Here the investigator will cover the desired outcome of the criminal act.

•

Access to the poison responsible for the death:

The criminal investigator must present such evidence as proof of sale of the poison, with such things as receipts or the signature on a poison register at the point of sale. Is there any original packaging, wrappers, or containers associated with the suspect? It may suffice to prove that a suspect has had access at a workplace, used toxins or poisons in his or her occupation, or had a hobby that involved the use of the poison in question.

•

Access to the victim:

Is there any proof that a suspect has knowledge of the victim’s daily habits, could have had the opportunity to overcome any of the victim’s normal defenses, and was able to administer the poison either directly or indirectly?

•

Death caused by poison:

There must be sufficient, sound evidence that would induce a reasonable person to come to this conclusion. Remember that in order to prove death by poison, the presence of the poison in the systemic circulation and/

or body organs must be proven. The presence of the poison only in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract does not prove death by poisoning. The GI tract from the mouth to the anus is much like a garden hose, hollow and open at both ends, and therefore outside the topological framework of the body. Consequently, to have met its fatal potential, the poisonous compound must have been absorbed through the walls of the gut and entered the body’s systemic circulation so that it could get to the site that caused the untoward effect.

•

Death homicidal:

This cannot be proven analytically or by autopsy but depends on the work of the criminal investigator at the crime scene, and examination of witnesses. This proof must categorically eliminate the possibility that the death resulted from an accident, intentional substance abuse, or an act of suicide.

In conclusion, to ensure the possibility of a conviction, it is imperative that proof of these investigational elements clearly leads to the conclusion Proving Poisoning

89

that the death was caused by poison, that the accused administered the poison to the deceased, that it is not possible or probable that any other person could have administered the substance, and that the accused was well aware of the poison’s lethal effects on the victim.