Criminal Poisoning: Investigational Guide for Law Enforcement, Toxicologists, Forensic Scientists, and Attorneys (18 page)

Authors: John H. Trestrail

7.2. STATISTICAL ANALYSES OF POISONINGS IN THE UNITED STATES

To my knowledge, no major epidemiological study has ever been done prior to the 1990s that reviews poisoning homicides in the United States. The first such study was carried out by Westveer, Trestrail, and Pinizotto (1996) and was published in 1996. These investigators decided to examine the data contained in the Uniform Crime Reports (UCR), maintained by the Department of Justice, from 1980 to 1989. These reports, submitted annually from police agencies across the United States, provide information on the victim and the offender in various crimes. This information includes the month; the year; the state; victim information (gender, age, and race); offender information (gender, age, and race); classification of the poisonous agent as drug, nondrug, or fume; the relationship between the victim and the offender; and a motive classification group. From 1980 to 1989, a total of 202,785 homicides were reported, and in this compilation, of all homicides, there were 292 poisoning cases of a single offender on a single victim. This total represents 14

poisoning cases per 10,000 homicides. The following information was determined from a statistical analysis of the UCR data: Gender relationships:

• The number of male victims and female victims was equal.

• If the victim was a female, the offender was usually a male.

• If the victim was a male, the offender could have been either a male or a female.

• Twice as many offenders were male than female.

Racial relationships:

• The victim and offender were usually of the same race.

• The victims were mostly white.

• If the victim was white, the offender was usually a male.

• If the victim was black, the offender was either a male or a female.

• Twice as many black victims were male than female.

• The number of female white victims and male white victims was equal.

• For black or white offenders, there were twice as many males as females.

Age characteristics:

• The number of victims was highest in the age range of 25–29 yr.

• The number of offenders was highest in the age range of 20–34 yr.

90

Criminal Poisoning

Geographic relationships:

• Poisonings average 1.47 per million people per year.

• Poisonings were highest in the western region; the state of California had the highest number.

Other relationships:

• Probably one of the most startling revelations from this study was that the unknown offender rate for poisoning cases was 20–30 times higher than for nonpoisoning homicides. This is another indication that law enforcement, as well as other forensic scientists, need to sharpen their investigative skills in the area of murder by poison.

• More victims did not have a relationship with the offender’s family. This is an unusual result, because it would seem that most homicidal poisonings would be a crime of the domestic environment.

• Nondrug poisons were used by 50% more males than females, and drug poisons were used by three times as many males as females.

• Poisoning rate by year or month was relatively constant. There was no month or year that showed a significant increase or decrease in the number of poisoning cases reported.

Westveer, Jarvis, and Jenson (2004) repeated the study just discussed.

They examined the data for the period of 1990–1999, and the results were very similar. They did find that there were 346 poisonings in the 186,971

total homicides for the decade. The incidence of 18 poisonings per 10,000

homicides represents an increase of 29% over the value found for the prior decade (Westveer, Jarvis, and Jenson, 2004).

Future analyses should examine the data that represent poisoning cases in which a single offender poisoned multiple victims—the serial poisoner—and the relatively rare cases that represent multiple offenders on a single victim.

7.3. REFERENCES

Doyle AC: A scandal in Bohemia. In:

The Complete Sherlock Holmes.

Doubleday & Co., Garden City, NY, 1930, p. 163.Westveer AE, Jarvis JP, Jenson CJ: Homicidal poisoning—the silent offense.

FBI Law Enforcement Bull

, August 2004:1–8.

Westveer AE, Trestrail JH, Pinizzoto J: Homicidal poisonings in the United States—an analysis of the Uniform Crime Reports from 1980 through 1989.

Am J Forensic Med Pathol

1996;17(4):282–288.

Westveer AE, Jarvis JP, Jensen CJ:

Homicidal poisoning—the silent offense. FBI Law Enforcement Bill.

August 2004: 1–8.

7.4. SUGGESTED READING

Browne GL, Stewart CG:

Reports of Trials for murder by poisoning

. Stevens and Sons, London, 1883.

Poisoners in Court

91

Poisoners in Court

“I have three rules. I never believe what the prosecutor or police say.

I never believe what the media say, and I never believe what my client says.”

—Attorney Alan M. Dershowitz

The majority of the death scene investigations have been completed.

Evidence has been gathered that points to a defendant as the probable perpetrator of a murder by means of poison. It is now time to take the evidence that proves method, motive, and opportunity to the jury. Let us take a look at some of the differences that might be encountered in the poisoning trial vs trials for murder by means of more traditional weapons.

To establish that the death was owing to poisoning, one must be able to prove the following (

see

Fig. 8-1

):

• That chain of custody was maintained, to include who had possession of the evidence, and when possession was taken.

• That the poison was present based on analysis.

• That the poison was absorbed systemically and was in the body’s circulation.

(Remember that the gut is much like a garden hose.)

8.1. BATTERY BY POISON

One may commit a battery by causing injury through poisoning. Battery, of course, occurs when a person is injured in a dangerous situation intentionally created by the defendant.

A defendant is held culpable in a battery charge if he or she acts with either intent to injure or criminal negligence. “Aggravated battery” is punish-able as a felony and results from actions taken with the intent to kill. In this From: Forensic Science and Medicine: Criminal Poisoning, Second Edition By: J. H. Trestrail, III © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ

91

92

Criminal Poisoning

Figure 8-1

case, usually the defendant must have intended to cause the specific result; otherwise the crime is considered a “regular battery.”

8.2. STANDARD DEFENSE ARGUMENTS

When a poisoner goes on trial, obtaining a conviction will be far from simple. It is at this point that the results of the investigator’s careful and detailed work will become critical. In this section, I discuss some prosecution strategies and defense tactics that might come into play.

Unlike in trials for murder that has been carried out by means of a visibly detectable weapon (e.g., gun, knife, rope), in trials for murder by poison, one must not forget that the vast majority of the trial evidence will be indirect evidence, or circumstantial evidence. In the poisoning crime, there will be few, if any, witnesses.

The defendant will attempt to explain the facts being presented by the prosecutor. The poisoner’s best defense is the simplest answer that explains the facts. Some of the possible counterarguments that may be attempted by the defense team are discussed next.

8.2.1. Poisoning Not the Cause of Death

The defense will attempt to prove that the poison did not cause the death, that the victim died from another cause. For example, the defense might argue Poisoners in Court

93

that the cause of death was a subdural hematoma from a fall. At this point, the detailed combined work of a forensic pathologist and an analytical toxicologist will come into play.

8.2.2. Poisoning Not Homicidal

The defendant will attempt to downplay his or her involvement in the death by trying to convince the court that the victim caused his or her death by self-administering the poison, either with suicidal intent or as the fatal result of substance abuse.

8.2.3. No Homicidal Intent

It could be suggested that the substance was administered by the accused but not with the intent to murder. One is reminded of the Arthur Ford case in the United Kingdom, discussed in Chapter 1, in which the offender administered candy containing cantharides in order to sexually arouse two secretaries in his office. He was convicted of manslaughter, because the court agreed that his intent was not to kill. Another case would be the unfortunate death of comedian John Belushi from an overdose of drugs administered by another person.

8.2.4. Substance Not a Poison

Legal experts will often argue over the acceptable definition of a “poison.” Is it a drug, and not a poison? Remember Paracelsus’ definition of a poison: that it is solely related to dose. The major factors that determine the potential lethality of any substance are concentration and duration of exposure. This was clearly stated in 1915 by the German chemist Fritz Haber, who developed what was known as the “CT product.” His formula was

C

×

T

= a constant. What this means is that the product of the concentration (

C

) of a poison and the survival time (

T

) of the victim is a constant value. For example, breathing a certain concentration of carbon monoxide for a specified amount of time will produce the same effects as breathing half the concentration for twice that time—the toxicological result should be a constant outcome.

8.2.5. The Accused Had a Reason

to Have the Poison in His or Her Possession

As to why the accused had the poisonous substance in his or her possession, it may be argued that it was acceptably associated with his or her job (e.g., chemist) or hobby (e.g., photography), or that the substance was being used as a domestic pesticide or herbicide to rid the area of unwanted pests or plants.

94

Criminal Poisoning

8.3. PROBLEMS IN PROVING INTENTIONAL POISONING

The attorney for the prosecution is bound to find himself or herself beset with some unique problems in a poisoning trial. One of the major problems is that the majority of the evidence will be circumstantial (indirect). In the typical murder by poison, there are no witnesses to the act. Another problem is that there may not be an accepted legal definition of a poison. There is also bound to be a great deal of dispute over the scientific evidence, and much of the evidence is likely to be rebutted by the defense’s technical experts.

The goal in obtaining a conviction is to prove that the death was caused by a poison, ideally with a combination of pathological and analytical evidence. It must be proven that the accused administered the poison because he or she had the access and opportunity, and that it is not possible or probable that any other person could have administered the substance. It is also imperative to prove that the accused was aware of the poison’s lethality.

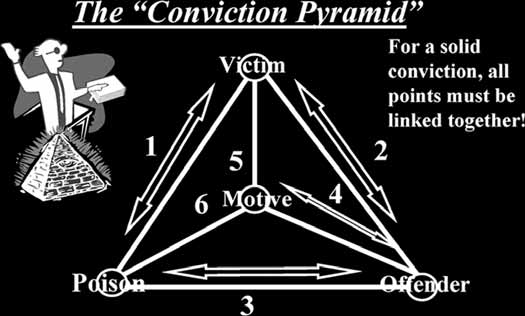

Is would be wise for the prosecution to prepare its case while keeping in mind what I have named the “Conviction Pyramid” (

see

Fig. 8-2

). This con-

cept represents the four major points that must be proven to be connected in the case: the victim, the poison, the offender, and the motive.

The case usually begins with the discovery of the two points representing leg 1, Victim-Poison, but the proof must also encompass the more difficult legs of the Conviction Pyramid numbered 2, 3, and 4: Offender-Victim, Offender-Poison, and Motive/Intent-Offender, respectively. Unless each of these points is unquestionably linked, there may be great difficulty in obtaining a conviction.

Laying out the poisoning case comes down to trying to solve the following quasi-algebraic equation, in which

A

= the plaintiff,

B

= the victim, and

X

= the poison:

•

B

= Dead! = the VICTIM (“who”)

•

X

is found in

B

= the

CAUSE

(“what”) •

A

had a reason for eliminating

B

=

MOTIVE

(“why”) •

A

obtained

X

=

METHOD

(“how”) •

A

had access to

B

=

OPPORTUNITY

(“when,” “where”) •

A

poisoned

B

=

ACCUSATION

(“offender who”) Always remember the logic argument known as Occam’s razor: the simplest solution to a problem is probably the correct one.

As one can see, the poisoning trial is beset with unique conviction pitfalls, but with proper investigational research, proper chain of evidence, and detailed planning, the chances of a conviction are greatly increased.