Criminal Poisoning: Investigational Guide for Law Enforcement, Toxicologists, Forensic Scientists, and Attorneys (19 page)

Authors: John H. Trestrail

Poisoners in Court

95

Figure 8-2

8.4. REFERENCE

Dershowitz AM, New York Times, October 28, 1994.

8.5. SUGGESTED READING

Boos WF:

The Poison Trail

. Hale, Cushman & Flint, Boston, 1939.

Glaister J:

The Power of Poison

. William Morrow and Company, New York, 1954.

Poisoning in Fiction

97

Poisoning in Fiction

MARTHA: “Well, dear, for a gallon of elderberry wine, I take one teaspoonful of arsenic, and add a half a teaspoonful of strychnine, and then just a pinch of cyanide.”—Arsenic and Old Lace, Joseph Kesselring It is often said that life can imitate art, and so it would behoove us to look at the use of poisons in fictional works, both written and visual. The scenario of an individual reading a novel or watching a film, and obtaining ideas that could lead to committing an actual murder, is not beyond the realm of possibility.

9.1. POISONS THAT HAVE BEEN USED IN BOOKS AND FILMS

In gathering information on how poisons have been used in fictional writing, I analyzed 187 texts. The types of poisons used varied slightly from those that have been used in actual cases of murder, but the primary ones did

appear. In fiction, cyanide was used more often than arsenic.

Table 9-1

summarizes the poisons used in fictional writings.

It is also important to look at the visual media as well, because some

movies can create ideas in the fertile mind of the poisoner.

Table 9-2

summarizes some of the films that have used poisons in their plots.

As part of the investigation of a criminal poisoning, it would be wise for the investigator to look at any fictional literature and visual media to which the suspect had access.

From: Forensic Science and Medicine: Criminal Poisoning, Second Edition Edited by: J. H. Trestrail, III © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ

97

98

Criminal Poisoning

Table 9-1

Poisons Used in the Literature (a Review of 187 Works) Poison

No. of cases

%

Acid

1

0.5

Aconite

2

1.1

Air (by injection)

1

0.5

Akee

1

0.5

Antimony

1

0.5

Arrow poison

1

0.5

Arsenic

13

7.0

Atropine

5

2.7

Barbitone

3

1.3

Bowl cleaner

1

0.5

Carbon monoxide

3

1.6

Chloral

1

0.5

Chloral hydrate

2

1.1

Coal gas

2

1.1

Cocaine

2

1.1

Coniine

1

0.5

Curare

4

2.1

Cyanea capillata

1

0.5

Cyanide

25

13.4

“Devil’s Foot Root”

1

0.5

Digitalin

3

1.6

Digitalis

3

1.6

Digitoxin

1

0.5

Drugs

1

0.5

Fear: of poison death

2

1.1

Food poisoning

1

0.5

Formic acid

1

0.5

Fungus

1

0.5

Gelsemium

1

0.5

Hemlock

1

0.5

Henbane

1

0.5

Hexabarbital

1

0.5

Hyoscine

3

1.6

Indian hemp + datura

1

0.5

Jimson weed

2

1.1

L-Thyroxine

1

0.5

Microorganisms: cholera

1

0.5

Poisoning in Fiction

99

Table 9-1 (Continued)

Poisons Used in the Literature (a Review of 187 Works) Poison

No. of cases

%

Morphine

6

3.2

Multiple poisons

1

0.5

Muscarine

1

0.5

Mushrooms

15

8.0

Narcotic

1

0.5

Nicotine

6

3.2

Nitrobenzene

2

1.1

Oleander

2

1.1

Paint thinner

1

0.5

Phenylbutazone allergy

1

0.5

Phosphorus

1

0.5

Photographic developer

1

0.5

Physostigmine

2

1.1

Poisoned darts

1

0.5

Poison gas

1

0.5

Procaine

1

0.5

Purvisine (an alkaloid)

1

0.5

Ricin

2

1.1

Serenite (an invented poison)

1

0.5

Solanine

1

0.5

Streptomycin allergy

1

0.5

Strophanthin

5

2.7

Strychnine

6

3.2

Taxine

1

0.5

Tetra-ethyl-pyrophosphate

1

0.5

Tetrodotoxin

1

0.5

Thallium

2

1.1

Toxin

1

0.5

Trinitrin

1

0.5

Tuberculin

1

0.5

Unidentified native poison

2

1.1

Unknown poison

13

7.0

Venom: bee

2

1.1

Venom: snake

4

2.1

Virus

1

0.5

Warfarin

1

0.5

Total

187

100.0

100

Criminal Poisoning

Table 9-2

Poisons Used in Motion Pictures (a Review of 15 Works) Film title

Date

Poison used

Attack of the Mushroom People

1964

Mushrooms

Beguiled, The

1971

Mushrooms

Black Widow

1987

Penicillin allergy + unknowns

Court Jester, The

1956

Unknown

Dead Pool, The

1988

Street drug

D.O.A.

1949

Iridium

D.O.A.

1988

Radium chloride

Fer-de-Lance

1974

Venom: snake

Flesh and Fantasy

1943

Aconite

Goliath Awaits

1981

Algae extract (Palmer’s disease)

Pope of Greenwich Village, The

1984

Lye (sodium hydroxide)

Serpent and the Rainbow, The

1988

Tetrodotoxin

Throw Mama from the Train

1987

Lye (sodium hydroxide)

Venom

1982

Venom: snake

Young Sherlock Holmes

1985

Dart poison

9.2. SUGGESTED READING

Bardell EB: Dame Agatha’s dispensary.

Pharm Hist

1984;26(1):13–19.

Bond RT:

Handbook for Poisoners: A Collection of Great Poison Stories.

Rinehart & Co., New York, 1951.

Corvasce MV, Paglino JR: Modus Operandi:

A Writer’s Guide to How Criminals Work.

The Howdunit Series, Writer’s Digest Books, Cincinnati, 1995.

Modus Operandi roman in title correct?

Done AK: History of poisons in opera.

Mithridata

(newsletter of the Toxicological History Society) 1992;2(2):3–13.

Foster N: Strong poison: chemistry in the works of Dorothy L. Sayers. In:

Chemistry and Crime,

Gerber SM, ed. American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, 1983, pp. 17–29.

Gerald MC:

The Poisonous Pen of Agatha Christie.

University of Texas Press, Austin, 1993.

Gwilt JR: Brother Cadfael’s herbiary.

Pharm J

December 19/26, 1992;807–809.

Gwilt PR: Dame Agatha’s poisonous pharmacopoeia.

Pharm J

1978;28&30:572, 573.

Gwilt PR, & Gwilt JR: The use of poison in detective fiction.

Clue: J Detection

1981; 1:8–17.

Kasselring J:

Arsenic and Old Lace.

New York Pocket Books, New York, 1944.

Reinert RE: There ARE toadstools in murder mysteries (part I).

Mushroom—J Wild Mushrooming

1991–92;10(1):5–10.

Reinert RE: There ARE toadstools in murder mysteries (part II).

Mushroom—J Wild Mushrooming

1994;12(2):9–12.

Poisoning in Fiction

101

Reinert RE: More mushrooms in mystery stories.

Mushroom—J Wild Mushrooming 1996–97;15(1):5–7.

Stevens SD, Klarner A:

Deadly Doses: A Writer’s Guide to Poisons.

The Howdunit Series, Writer’s Digest Books, Cincinnati, 1990.

Tabor E: Plant poisons in Shakespeare.

Econ Bot

1970;24:81–94.

Thompson CJS: Poisons in fiction. In:

Poison Mysteries in History, Romance, and Crime (Thompson CJS, ed), J.B. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1924, pp. 254–261.

Winn D:

Murder Ink: The Mystery Reader’s Companion.

Workman Publishing, New York, 1977.

Winn D:

Murderess Ink: The Better Half of the Mystery.

Workman Publishing, New York, 1979.

Conclusion

103

Conclusion

“If all those buried in our cemeteries who were poisoned could raise their hands, we would probably be shocked by the numbers!”—John H. Trestrail III As Sir Arthur Conon Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stated to his partner, Dr.

Watson, “The game is afoot,” so it is with investigators and the criminal poisoner

.

As homicide investigators, we must always remember that unless we remain ever vigilant, we will lose the game. Unless the possibility of poisoning is considered in the first place, the critical evidence of the crime will most likely be buried with the victim, and the poisoner will walk off into the sun-set, with a feeling of superior intellect and smugness.

The

prime directive

for any criminal investigation is that

every death must be considered a homicide until the facts prove otherwise.

To this we must now add a new

subdirective

for the criminal investigation of homicidal poisonings:

Every death with no visible signs of trauma must be considered a poisoning until the facts prove otherwise.

The investigative key is to put all the clues together, and where they overlap, one should be able to match the most probable offender. So let us review the basic categories of clues as they relate to poisoning homicides: •

WHO

was the victim? Was the victim a specific or random target? Could it be a camouflaged

poisoner hiding behind a tampering? Why would anyone want to kill this individual, as determined by their “victimology”? (

see

Fig. 10-1

).

•

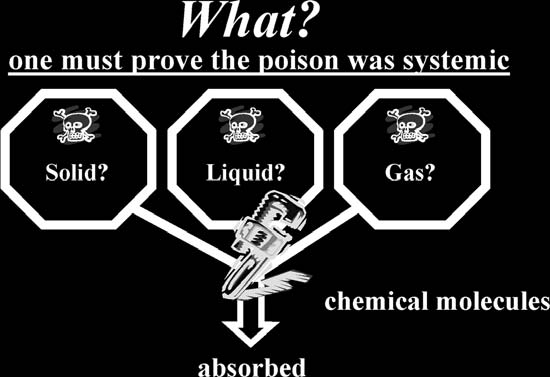

WHAT

was the poisoning weapon? Remember that whether it is a solid, liquid, or gas, they are just atoms and molecules, which carry out their biochemical destruction in the manner of a “chemical monkey wrench.” Never forget that it is imperative that the poison be proven to have been in the victim’s systemic circulation (

see

Fig. 10-2

).

From: Forensic Science and Medicine: Criminal Poisoning, Second Edition By: J. H. Trestrail, III © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ

103

104

Criminal Poisoning

Figure 10-1

Figure 10-2

•

WHERE

did the crime take place? Remember that a poisoning may have multiple crime scenes (procurement, preparation, administration, disposal, and ultimately the death scene) (

see

Fig. 10-3

).

•

WHEN

was the poison administered to the victim? Remember that the time from administration till death is dependent on the concentration and toxicity of the substance. With an acute dose one sees sudden onset. Carry out analyses on blood, urine, and gastric contents (BUG). Look for poisons that have a rapid action (e.g.,