Daily Life in Elizabethan England (27 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

UNDERGARMENTS

The principal undergarment for both men and women was the shirt,

which served as a comfortable, absorbent, and washable layer between the body and the outer clothes. Shirts had long sleeves and were pulled over the head. They were generally made of white linen, although the rich favored silk. Shirts tended to be simple in cut, with straight seams, but the fabric might be heavily gathered at the collar and cuffs. Fancy shirts were sometimes decorated with lace or adorned with black, red, or gold

Clothing and Accoutrements

131

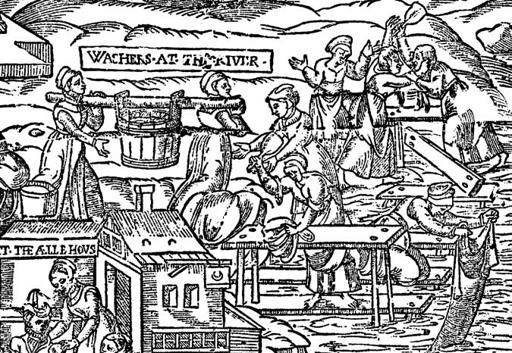

Laundresses at work. [Besant]

embroidery, especially about the collar, shoulders, and cuffs. Men’s shirts typically reached to the crotch or thigh and were vented at the bottom of the side seams to allow for greater freedom of movement. Women’s shirts, usually called

smocks,

were normally between knee-and ankle-length. Triangular gores of fabric inserted into the side seams allowed extra mobility in these longer garments. The neckline of a woman’s smock might be high or low. For many people the shirt also served as a nightgown, although wealthy people had nightshirts for this purpose.

The shirt was more truly an undergarment than it is today. People who were not manual laborers were almost never seen in their shirtsleeves, although gentlemen might strip to their shirts for respectable physical exertion (such as tennis). Working people were sometimes seen in their shirts when they had to perform heavy labor, but women would at least wear a sleeveless bodice on top.

In addition to the shirt, men often wore undershorts comparable to modern boxer shorts. These were generally called

breeches,

an ambiguous term since it could refer to an outer garment as well. Women did not normally wear breeches in England, although they had started to do so in Italy. Breeches were made of white linen and might be adorned with embroidery, especially about the cuffs.

132

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

WOMEN’S GARMENTS

On top of her smock, an Elizabethan woman might wear any of three

general styles of attire, sometimes in combination with each other. The first was the

kirtle,

the second was a bodice and

petticoat

(skirt), and the third was a gown.

The kirtle was a long fitted garment reaching down to the feet, resembling a long close-fitting dress. It was a fairly simple style, derived from medieval garments, and was not generally worn by itself among fashionable women, although it might be worn under another garment.

The bodice, or

pair of bodies,

was a close-fitting garment for the upper body, normally made of wool. It kept the torso warm and was stiffened to mold the body into the fashionable shape. This shape was rather severe and masculine: flat, broad in the shoulders, and narrow in the waist. In effect, the bodice combined the functions of bra, girdle, and vest all in one. Its waistline was pointed in front. The neckline reflected the trends of fashion: it was low toward the beginning and end of Elizabeth’s reign, high during the middle years. A low bodice might be worn with a high-neckline smock; the decolleté look was normal only with young unmarried women and in some fashionable circles. The bodice had no collar.

DRESSING A GENTLEWOMAN

Where be all my things? Go fetch my clothes: bring my petticoat bodies

[bodice]: I mean my damask quilt bodies with whale bones. What lace do you give me here? This lace is too short, the tags are broken . . . Give me my petticoat of wrought crimson velvet with silver fringe. Why do you not give me my nightgown?—for I take cold. Where be my stockings? Give me some clean socks. I will have no worsted hosen, show me my carnation silk stockings. Where laid you last night my garters? . . . Put on my white pumps.

Set them up, I will have none of them. Give me rather my Spanish leather shoes, for I will walk today. This shoeing-horn hurteth me . . . Tie the strings with a strong double knot, for fear they untie themselves. Jolie, come dress my head, set the table further from the fire, it is too near. Put my chair in his place. Why do you not set my great looking glass on the table? . . . Where is my ivory comb? . . . Take the key of my closet, and go fetch my long box where I set my jewels . . . Go to, Page, give me some water to wash. Where’s my musk ball? Do you not see that I want my busk? What is become of the busk-point? . . . Let me see that ruff, How is it that the supporter is so soiled? . . . I believe that the meanest woman in this town hath her apparel in better order than I have. . . . Is there no small pins for my cuffs? Look in the pin-cushion. . . . Bring my mask and my fan; help me to put on my chain of pearls.

Peter Erondell,

The French Garden

(1605), in M. St Clare Byrne, ed.

The Elizabethan

Home

(London: Methuen, 1949), 37–38.

Clothing and Accoutrements

133

The bodice could be sleeved or sleeveless. A sleeveless bodice was considered an adequate outer garment for women when they were doing

heavy work, although they always wore a sleeved bodice or overgarment in less informal situations. Women of higher social status had no cause to be seen in their shirtsleeves, so a sleeveless bodice for them was solely an undergarment. A sleeved bodice might be worn on top of a sleeveless one.

The sleeves were sometimes detachable, allowing for a change of sleeves to be laced or hooked in—a cheap way to change the look of the garment.

If a sleeveless bodice was worn underneath, the outer bodice did not need to be as heavily stiffened. Bodices often had decorative tabs called

pickadills

about the waist; if worn on the outside, they might have rolls or wings of fabric around the armholes.

The degree of stiffening in the bodice depended on the wearer’s station in life. Upper-class women wore stiffly shaped bodices, but ordinary women needed more freedom of movement to perform everyday tasks (such as churning butter, baking bread, or chasing children), so their garments had to be less constricting. Stiffening might be provided by whale-bone (baleen), bundles of dried reeds, willowy wood, or even steel. A less fashionable bodice might be shaped with just a heavy buckram interlining. To get the fashionably flat look in front, a rigid piece of wood, bone, or ivory, called a

busk,

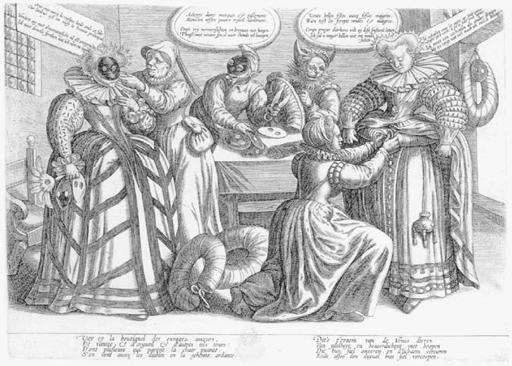

might be inserted and held in place by a ribbon at A satirical print on women’s fashions, ca. 1595. [Bibliothèque nationale de France]

134

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

the top; to this day women’s undergarments often have a small bow in the midpoint of the chest, the last trace of the Elizabethan busk.

A bodice worn as an innermost garment took a fair bit of strain, so buttons would have been too weak a fastening. Instead, bodices were fastened with hooks and eyes, or else were laced up. Ordinary women’s bodices usually laced up the front; side-and back-lacing bodices were worn by people who had servants to help them dress. The innermost bodice sometimes had holes around the bottom edge to which a farthingale, roll, or petticoat could be laced.

On top of a sleeveless bodice, women sometimes wore doublets similar to those worn by men. Unlike a bodice, the doublet had a collar and buttoned up the front.

Where the bodice served to flatten and narrow the upper body, Elizabethan fashion called for volume in the lower body. This was generally achieved either with a

farthingale

or a

roll,

or with a combination of the two. The farthingale had originated in Spain as a bell-shaped support for the skirts: it was essentially an underskirt with a series of wire, whale-bone, or willow hoops sewn into it. During the course of Elizabeth’s reign, the

wheel farthingale

was introduced. This stuck directly out at the hips and fell straight down, giving the skirts a cylindrical shape. The wheel farthingale was often worn with a padded roll about the hips. Sometimes the roll was worn by itself to give a somewhat softer version of the wheel farthingale look. This style was particularly common among ordinary people, for whom it served not only to imitate the fashionable shape but also to keep the skirts away from the legs for greater ease of movement.

Skirts were known as

petticoats.

Their shape was dictated by the shape of the undergarments. Bell-shaped farthingales required skirts of similar Country women and a water carrier; detail from “Elizabeth I’s Procession Arriving at Nonesuch Palace,” 1582, by Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1600) [Private Collection/

The Bridgeman Art Library]

Clothing and Accoutrements

135

proportions, lightly gathered at the waist and made in several trapezoidal panels. Wheel farthingales required huge skirts, heavily gathered to the waist. Women who did not wear farthingales might wear many layers of petticoats to create volume (as well as warmth). The ordinary woman’s outer petticoat was of wool; underpetticoats might be of linen and were sometimes richly embroidered. Often, hems were made of a different, more durable fabric that could be removed and replaced as they wore out.

The final main style of female garment was the gown, which was essentially a bodice and skirt sewn together, usually worn on top of a kirtle or petticoat. The gown was the richest form of garment, and it took many forms. The bodice was frequently adorned with false sleeves that hung down at the back, and often the skirt was open in front to reveal the contrasting skirts underneath.

MEN’S GARMENTS

Lower-body garments for men changed substantially during the course of Elizabeth’s reign. In the early years, some people still wore the old-fashioned

long hose

and

codpiece,

a style that had changed little since the late Middle Ages. The hose were loose-fitting leggings roughly analogous to modern tights. They were often made of woven rather than knitted fabric. The fabric was usually wool (which is naturally somewhat elastic) and cut on the bias (i.e., diagonally) to allow them to stretch, but they still tended to bag, especially around the ankles. The codpiece was a padded covering for the crotch, originally introduced for the sake of propriety. It also served the function of a modern trouser-fly: it could be unbuttoned or untied when nature called.

This plain style of hose was already out of fashion by the time Elizabeth came to the throne. Well-dressed men had taken to wearing

trunkhose

over their long hose. These were an onion-shaped, stuffed garment that extended from the waist to the tops of the thighs. The trunkhose were often slashed vertically or constructed from multiple vertical panes, revealing a contrasting fabric underneath.

Later in the reign, a new fashion arose of attaching

canions

to these trunkhose. These were tight-fitting cylindrical extensions that reached from the bottom of the trunkhose to the wearer’s knees. At the same time, the trunkhose themselves became fuller and longer, reaching to midthigh, and were more likely to be of a solid fabric rather than slashed or paned.