Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1227 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

I do not know what subsequent reports prevented justice from being done at the Home Office — (there lies the wickedness of the concealed dossier) — but this I do know, that, instead of leaving the fallen man alone, every possible effort was made after the conviction to blacken his character, and that of his father, so as to frighten off anyone who might be inclined to investigate his case. When Mr. Yelverton first took it up, he had a letter over Captain Anson’s own signature, saying, under date Nov. 8, 1903: “It is right to tell you that you will find it a simple waste of time to attempt to prove that George Edalji could not, owing to his position and alleged good character, have been guilty of writing offensive and abominable letters. His father is as well aware as I am of his proclivities in the direction of anonymous writing, and several other people have personal knowledge on the same subject.”

Now, both Edalji and his father declare on oath that the former never wrote an anonymous letter in his life, and on being applied to by Mr. Yelverton for the names of the “several other people” no answer was received. Consider that this letter was written immediately after the conviction, and that it was intended to nip in the bud the movement in the direction of mercy. It is certainly a little like kicking a man when he is down.

Since I took up the case I have myself had a considerable correspondence with Captain Anson. I find myself placed in a difficult position as regards these letters, for while the first was marked “Confidential,” the others have no reserve. One naturally supposes that when a public official writes upon a public matter to a perfect stranger, the contents are for the public. No doubt one might also add, that when an English gentleman makes most damaging assertions about other people he is prepared to confront these people, and to make good his words. Yet the letters are so courteous to me personally that it makes it exceedingly difficult for me to use them for the purpose of illustrating my thesis — viz., the strong opinion which Captain Anson had formed against the Edalji family. One curious example of this is that during fifteen years that the vicarage has been a centre of debate, the chief constable has never once visited the spot or taken counsel personally with the inmates.

For three years George Edalji endured the privations of Lewes and of Portland. At the end of that time the indefatigable Mr. Yelverton woke the case up again, and Truth had an excellent series of articles demonstrating the impossibility of the man’s guilt Then the case took a new turn, as irregular and illogical as those which had preceded it At the end of his third year, out of seven, the young man, though in good health, was suddenly released without a pardon. Evidently the authorities were shaken, and compromised with their consciences in this fashion. But this cannot be final. The man is guilty, or he is not If he is he deserves every day of his seven years. If he is not then we must have apology, pardon, and restitution. There can obviously be no middle ground between these extremes.

And what else is needed besides this tardy justice to George Edalji? I should say that several points suggest themselves for the consideration of any small committee. One is the reorganisation of the Staffordshire Constabulary from end to end; a second is an inquiry into any irregularity of procedure at Quarter Sessions; the third and most important is a stringent inquiry as to who is the responsible man at the Home Office, and what is the punishment for his delinquency, when in this case, as in that of Beck, justice has to wait for years upon the threshold, and none will raise the latch. Until each and all of these questions is settled a dark stain will remain upon the administrative annals of this country.

I have every sympathy for those who deprecate public agitations of this kind on the ground that they weaken the power of the forces which make for law and order, by shaking the confidence of the public. No doubt they do so. But every effort has been made in this case to avoid this deplorable necessity. Repeated applications for justice under both Administrations have met with the usual official commonplaces, or have been referred back to those who are obviously interested parties.

Amid the complexity of life and the limitations of intelligence any man may do an injustice, but how is it possible to go on again and again reiterating the same one? If the continuation of the outrages, the continuation of the anonymous letters, the discredit cast upon Gurrin as an expert, the confession of a culprit that he had done a similar outrage, and finally the exposition of Edalji’s blindness, do not present new fact to modify a jury’s conclusion, what possible new fact would do so? But the door is shut in our faces. Now we turn to the last tribunal of all, a tribunal which never errs when the facts are fairly laid before them, and we ask the public of Great Britain whether this tiling is to go on.

Arthur Conan Doyle Undershaw, Hindhead January, 1907.

CASE OF GEORGE EDALJI: LETTER FROM SIR A. CONAN DOYL

E

FACSIMILE DOCUMENTS — No.

1

Some six weeks ago a correspondent in the Midlands wrote to me to the effect that the police, when driven out of the position that George Edalji committed the crime for which he was sentenced to seven years’ penal servitude, would endeavour to defend a second line — namely, that he had written the anonymous letters, and was therefore responsible for the mistake to which he fell a victim. The insight or the information of the writer has seemed to be correct, and this is, indeed, the defence which has been set up, with such success that it has prevented the injured man from receiving that compensation which is his due. In this article I ask your permission to examine this contention, and I hope I shall satisfy your readers, or enable them to satisfy themselves, that the supposition is against all reason or probability, and that a fresh injustice and scandal will arise if it should retard the fullest possible amends being made to this most shamefully-treated man.

During an investigation of this case, which has now extended over five months, I have examined a very large number of documents, and tested a long series of real and alleged facts. During all that time I have kept my mind open, but I can unreservedly say that in the whole research I have never come across any considerations which would make it, I will not say probable, but in any way credible, that George Edalji had anything to do, either directly or indirectly, with the outrages or with the anonymous letters. As the latter question seems to be at the bottom of the ungenerous decision not to give Edalji compensation, I will, with your permission, place some of the documents before your readers, so that they may form their own opinion as to how far the contention that Edalji wrote them can be sustained.

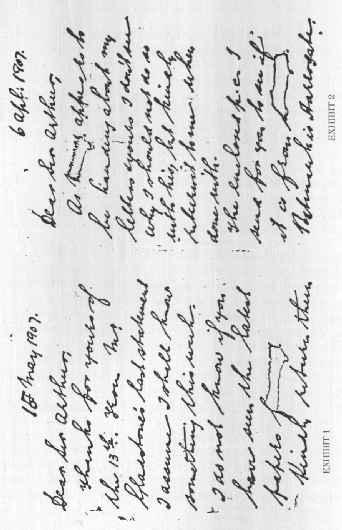

First, I will take the mere question of the handwriting of the letters, and secondly, I will take the internal evidence of their contents. The exhibits, which I will call 1 and 2, are specimens of Edalji’s ordinary writing, which is remarkably consistent in the many samples which I have observed. He says, and 1 believe with truth, that he has little power of varying his script. No proof has ever been adduced that he has such power. The specimens here given may be open to the objection that they arc four years later than the time of the outrages, but Edalji was twenty-seven years of age then, and is now thirty-one, and no marked development of writing is likely to occur in the interval. I give two separate specimens that the consistency of their peculiarities may be observed:

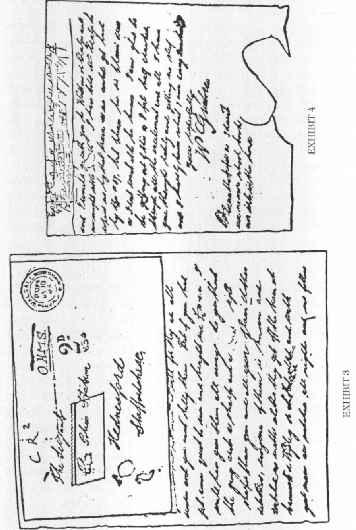

I now, for purposes of comparison, give two samples of those letters in 1903 which Mr. Gurrin, the expert who was at fault in the Reck case, declared to be, to the best of his belief, in the writing of George Edalji. To the ruin of the young man he persuaded the jury to adopt his view, and now the committee chosen by the Home Office has endorsed the opinion of the jury, with the result that compensation has been withheld. Exhibits 3 and 4 give specimens of the anonymous letters of 1903.

Now, on comparing the two specimens of Edalji with the two anonymous letters, the first general observation, before going into any details, is that the former is the writing of an educated man, and that the latter is certainly not so. A forger may imitate certain details in writing. A curious fashion of forming a letter is within the powers of even a clumsy imitator. Rut character is more difficult, and more subtle. Compare the real Edalji writing with the addressed envelope of three, or with the postscript of four, and ask yourself whether they do not belong to an entirely different class. Apart from the question of educated as against uneducated writing, the most superficial observer of character, as expressed in writing, would say that one and two were open and free, while three and four were cramped and mean. Yet Mr. Gurrin, the jury, and the Home Office Committee contend that they are the same, and a man’s career has been ruined on the resemblance.

Now let us examine the details. There are one or two points of resemblance which are sufficiently close to make me believe that it is not entirely coincidence, and that there may have been some conscious, though very imperfect imitation, of Edalji’s writing. One of these is a very small twirl made occasionally in finishing a letter. It is visible in the c in the fourth line from the bottom of exhibit two, and in the c of the word “clothes” fifth line from the bottom of three. A close inspection might detect it in several letters of both exhibits, and I am told that it was more common in Edalji’s writing of that date. Another resemblance is the long upward stroke in beginning such words as “kindly” in two, and “known” four lines from the bottom of three. This formation, however, is not unusual. Lastly, there is the r, which might occasionally almost be an e, as in “return” in two, and in “sharp” in three. These peculiarities, especially the last, are so marked that they are, one would imagine, the first points which anyone disguising his hand would suppress, and anyone imitating would reproduce.

But now consider the points of difference. See the peculiar huddling of the letters together appearing in such words as “brought,” “sharper,” and “would,” in 3, or in “don’t” “write,” and “known,” in 4. Where is there any trace of this in Edalji’s own writing ? Compare the rounded “g” of the whether they do not belong to an entirely different class. Apart from the question of educated as against uneducated writing, the most superficial observer of character, as expressed in writing, would say that one and two were open and free, while three and four were cramped and mean. Yet Mr. Gurrin, the jury, and the Home Office Committee contend that they are the same, and a man’s career has been ruined on the resemblance.

Now let us examine the details. There are one or two points of resemblance which are sufficiently close to make me believe that it is not entirely coincidence, and that there may have been some conscious, though very imperfect imitation, of Edalji’s writing. One of these is a very small twirl made occasionally in finishing a letter. It is visible in the c in the fourth line from the bottom of exhibit two, and in the c of the word “clothes” fifth line from the bottom of three. A close inspection might detect it in several letters of both exhibits, and I am told that it was more common in Edalji’s writing of that date. Another resemblance is the long upward stroke in beginning such words as “kindly” in two, and “known” four lines from the bottom of three. This formation, however, is not unusual. Lastly, there is the r, which might occasionally almost be an e, as in “return” in two, and in “sharp” in three. These peculiarities, especially the last, are so marked that they are, one would imagine, the first points which anyone disguising his hand would suppress, and anyone imitating would reproduce.

But now consider the points of difference. See the peculiar huddling of the letters together appearing in such words as “brought,” “sharper,” and “would,” in 3, or in “don’t,” “write,” and “known,” in 4. Where is there any trace of this in Edalji’s own writing ? Compare the rounded “g” of the anonymous letters with the straight “g” of Edalji. Compare the filled “r” of Edalji as seen in “Dear Sir Arthur,” with the final “r” of “matter” and “your” in 3, or of “paper” and “nor” in the postscript of 4. Finally, take a very delicate test, beyond the power of observation of a clumsy forger. If you take the letter “u” in Edalji’s letters you will find that he has a very curious and consistent habit of dropping the second curve of the “u” to a lower level than the first one. There is hardly an exception. But the anonymous writer, in three cases out of four, has the second curve as high as, or higher than, the first. Can any impartial and fair-minded man, examining these exhibits, declare that there is such an undoubted resemblance that a man’s career might be staked upon it, or that the public is exonerated by it from making reparation for an admitted wrong ?

So much for the actual writing. The matter becomes perfectly grotesque when we examine the internal evidence of the letters. In the first place, they are written for the evident purpose of exciting the suspicions of the police against two persons — the one being Edalji himself, and the other being young Greatorex, whose name was forged at the end of them. Why should Edalji, an eminently sane young lawyer, with a promising career before him, write to the police accusing himself of a crime of which he was really innocent? The committee speak of a spirit of impish mischief. What evidence of such a spirit has ever been shown in the life of this shy, retiring man? Such an action would appear to me to be inconsistent with sanity, and yet Edalji has always been eminently sane. What possible evidence is there to support so incredible a supposition? And suppose such a thing were true, how then would the introduction of young Greatorex be explained? Young Greatorex and Edalji were practically strangers. They had at most met without conversation when chance threw ‘them into the same railway carriage on the Walsall line. There was no connection between them, no cause of quarrel, no possible reason why Edalji should involve Greatorex in a terrible suspicion, and then voluntarily come to share his danger. The whole supposition is monstrous. But it all becomes clear when we regard the letters as the work of a third person, who was the enemy both of Edalji and of Greatorex, and who hoped by this device to bring down both his birds with one stone. That Edalji had enemies, who had brought ingenious mystifications in letter writing to a fine point is shown by the persecution to which he and his family were subjected from 1892 to 1895. One has only to show that one of those persecutors had also reason to wish evil to young Greatorex, and then it needs no fancifed theories of people writing scurrilous letters about themselves to make the whole situation perfectly credible and clear.

A priori, then, the likelihood of the letters being by Edalji is so slight that nothing but the most marked resemblance in the script could for a moment justify such a supposition. How far such an overpowering resemblance exists the reader can now judge for himself. But apart from the inherent improbability of such a theory, look at all the other points which should have laughed it out of court. Edalji was a well-educated young man, brought up in a clerical atmosphere, with no record of coarse speech or evil life. From his school days at Rugeley, where his headmaster gave him the highest character, until the time when he won the best prizes within his reach at the Legal College of Birmingham, there is nothing against his conduct or his language. Yet these letters are written by a foul-mouthed boor, a blackguard who has a smattering of education, but neither grammar nor decency. They do not as the Committee have said, actually prove that the writer was the man who did the outrages, but they at least show that he had a cruel and bloodthirsty mind, which loved to dwell upon revolting details. “I caught each under the belly, but they did not spurt much blood.” “We will do twenty wenches like the horses.” “He pulls the hook smart across ‘em and out the entrails fly.” This is the writing of a hardened ruffian. Where in Edalji’s studious life has he ever given the slightest indications of such a nature? His whole career and the testimony of all who have known him cry out against such a supposition.

Finally, there are certain allusions in the letters which are altogether outside Edalji’s possible knowledge. In one of them some seven or eight people are mentioned, all of whom live in a group two stations down the line from Wyrley, and entirely removed from Edalji’s very limited circle. They were a group immediately surrounding young Greatorex, and they were put in with a view to substantiating the pretence that he was the writer, for the entanglement of Greatorex was evidently the plotter’s chief aim, and the ruin of Edalji was a mere by-product in the operation. One of the people mentioned was the village dressmaker, a second the doctor, a third the butcher, all in the neighbourhood of Greatorex and out of the ken of Edalji. In his attempt to entangle Greatorex the writer actually gave himself away, as it is clear to any intelligence above that of a prejudiced official that he must be one of the very limited number of people who was himself acquainted with this particular group.