Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1231 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

and the writer said he had gone up to London from Birmingham that day. On enquiry Mr. Beaumont, of Wolverhampton Road, Cannock, — who has assisted me much —

discovered that Royden Sharp had actually left Cannock for Birmingham upon the morning of that same day — 19th. Mr. Hunt, the local station master, was his informant I will now recapitulate in condensed form the statement which has been here set out at length. Royden Sharp can be shown to have been the culprit:

1.

Because of his showing the weapon to Mrs. Greatorex.

2.

Because the wounds could only be produced by such an instrument as he showed.

3.

Because only such an instrument fits in with the description in the letters.

4.

Because being a butcher and a man from a cattle ship he was able to do such crimes which would be very hard for any ordinary man.

5.

Because in many points of the anonymous letters there is internal evidence pointing to Royden Sharp.

6.

Because he had a proved record of writing anonymous letters, of forgery, of diabolical mischief, and of bearing false witness, all of which qualities came out here.

7.

Because he went to Rotherham at the time when letters bearing on the crimes came from Rotherham.

8.

Because he is correctly described by a girl, who saw a man endeavouring to carry out, or pretend to carry out, the threats in the letters.

9.

Because the actual handwriting in many of the letters bears a resemblance to Royden Sharp’s own old writing. It is impossible now to get any specimen of his actual writing, as he is most guarded in writing anything. Why should he be if he is innocent?

10.

I am informed (but have not yet verified the fact) that in one of the anonymous letters occurs the phrase, “I am as Sharp as Sharp can be.”

This seems to me to be in itself a complete case, and if I — a stranger in the district — have been able to collect it, I cannot doubt that fresh local evidence would come out after his arrest. He appears to have taken very little pains to hide his proceedings, and how there could have been at any time any difficulty in pointing him out as the criminal is to me an extraordinary thing.

If further evidence were needed in order to assure a conviction, there are two men who could certainly supply it. These men are: —

Harry Green, formerly of Wyrley Farm, Wyrley, now in South Africa.

The other is Jack Hart, Butcher, Bridgtown, near Cannock.

Either of these men, if properly handled, would certainly turn King’s evidence. They both undoubtedly knew all about Sharp. Others who know something, but possibly not enough, as they were only on the edge of the affair, are Fred Brookes (formerly of Wyrley, now in Manchester), Thomas, and Grinsell, all of the local Yeomanry. It seems to me that Sharp did no more outrages with his own hands after the arrest of Edalji in August The next outrage was admittedly done by Harry Green, who can be shown, when in doubt as to what he should do, to have sent a note to someone else, which note was answered from London in a letter written on telegram forms, now to be seen in the Home Office. This answer was, I believe from the writing, from Royden Sharp. It is worth noting on the evidence of Mr. Arrowsmith, of the Cannock Star Tea Company, who has done most excellent work on this case, that Green accepted all Arrowsmith’s remarks good-humouredly, but on the latter saying “Sharp should be where Edalji now is,” he at once became very angry. The November outrage was done upon Stanley’s horses by

Jack Hart, the butcher, acting in collusion with Sharp. This makes really a separate case.

If it should be found possible to get Mrs. Sharp in the box, she would depose as she has told Mrs. Greatorex, that Royden Sharp is strangely affected by the new moon, and that on such occasions she had to closely watch him. At such times he seems to be a maniac, and Mr. Greatorex has himself heard him laughing like one. In this connection it is to be observed that the first four outrages occurred on February 2, April 2, May 3, and June 6, which in each case immediately follows the date of the new moon. The point of a connection between the outrages and the moon is referred to in one of the “Greatorex” letters, so it was present in the mind of the writer.

I cannot end this statement without acknowledging how much I owe to the unselfish exertions of Mr. Greatorex, of Littleworth Farm, Mr. Arrowsmith, of the Star Tea Company, Cannock, and Mr. Beaumont, of Wolverhampton Road, Cannock, without whose help I should have been powerless.

(Signed) Arthur Conan Doyle.

Undershaw, Hindhead

E

R

SPECIAL INVESTIGATION BY SIR A. CONAN DOYLE

Due to the success of the Sherlock Holmes stories, many people wrote letters to Conan Doyle over the years, asking him for help with real life crimes. The two most famous examples were George Edalji and Oliver Slater. Conan Doyle’s involvement in both these cases led to the establishment of the Court of Criminal Appeal in both England and Scotland.

In

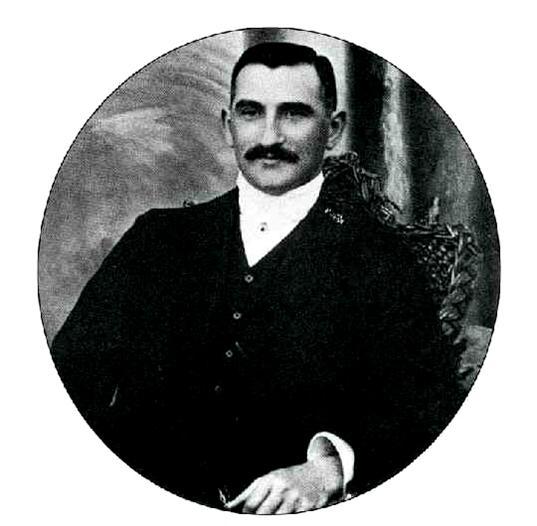

Oscar Slater, 1908

CONTENTS

IT is impossible to read and weigh the facts in connection with the conviction of Oscar Slater in May, 1909, at the High Court in Edinburgh, without feeling deeply dissatisfied with the proceedings, and morally certain that justice was not done. Under the circumstances of Scotch law I am not clear how far any remedy exists, but it will, in my opinion, be a serious scandal if the man be allowed upon such evidence to spend his life in a convict prison. The verdict which led to his condemnation to death, was given by a jury of fifteen, who voted: Nine for “Guilty,” five for “ Non-proven,” and one for “ Not Guilty.” Under English law, this division of opinion would naturally have given cause for a new trial. In Scotland the man was condemned to death, he was only reprieved two days before his execution, and he is now working out a life sentence in Peterhead convict establishment. How far the verdict was a just one, the reader may judge for himself when he has perused a connected story of the case.

There lived in Glasgow in the year 1908, an old maiden lady named Miss Marion Gilchrist. She had lived for thirty years in the one flat, which was on the first floor in 15, Queen’s Terrace. The flat above hers was vacant, and the only immediate neighbours were a family named Adams, living on the ground floor below, their house having a separate door which was close alongside the flat entrance. The old lady had one servant, named Helen Lambie, who was a girl twenty-one years of age. This girl had been with Miss Gilchrist for three or four years. By all accounts Miss Gilchrist was a most estimable person, leading a quiet and uneventful life. She was comfortably off, and she had one singular characteristic for a lady of her age and surroundings, in that she had made a collection of jewelry of considerable value. These jewels, which took the form of brooches, rings, pendants, etc., were bought at different times, extending over a considerable number of years, from a reputable jeweller. I lay stress upon the fact, as some wild rumour was circulated at the time that the old lady might herself be a criminal receiver. Such an idea could not be entertained. She seldom wore her jewelry save in single pieces, and as her life was a retired one, it is difficult to see how anyone outside a very small circle could have known of her hoard. The value of this treasure was about three thousand pounds. It was a fearful joy which she snatched from its possession, for she more than once expressed apprehension that she might be attacked and robbed. Her fears had the practical result that she attached two patent locks to her front door, and that she arranged with the Adams family underneath that in case of alarm she would signal to them by knocking upon the floor.

It was the household practice that Lambie, the maid, should go out and get an evening paper for her mistress about seven o’clock each day. After bringing the paper she then usually went out again upon the necessary shopping. This routine was followed upon the night of December 21st She left her mistress seated by the fire in the dining-room reading a magazine. Lambie took the keys with her, shut the flat door, closed the hall door downstairs, and was gone about ten minutes upon her errand. It is the events of those ten minutes which form the tragedy and the mystery which were so soon to engage the attention of the public.

According to the girl’s evidence, it was a minute or two before seven when she went out. At about seven, Mr. Arthur Adams and his two sisters were in their dining-room immediately below the room in which the old lady had been left. Suddenly they heard “ a noise from above, then a very heavy fall, and then three sharp knocks.” They were alarmed at the sound, and the young man at once set off to see if all was right. He ran out of his hall door, through the hall door of the flats, which was open, and so up to the first floor, where he found Miss Gilchrist’s door shut. He rang three times without an answer. From within, however, he heard a sound which he compared to the breaking of sticks. He imagined therefore that the servant girl was within, and that she was engaged in her household duties. After waiting for a minute or two, he seems to have convinced himself that all was right. He therefore descended again and returned to his sisters, who persuaded him to go up once more to the flat. This he did and rang for the fourth time. As he was standing with his hand upon the bell, straining his ears and hearing nothing, someone approached up the stairs from below. It was the young servant-maid, Helen Lambie, returning from her errand. The two held council for a moment. Young Adams described the noise which had been heard. Lambie said that the pulleys of the clothes-lines in the kitchen must have given way. It was a singular explanation, since the kitchen was not above the dining-room of the Adams, and one would not expect any great noise from the fall of a cord which suspended sheets or towels. However, it was a moment of agitation, and the girl may have said the first explanation which came into her head. She then put her keys into the two safety locks and opened the door.

At this point there is a curious little discrepancy of evidence. Lambie is prepared to swear that she remained upon the mat beside young Adams. Adams is equally positive that she walked several paces down the hall. This inside hall was lit by a gas, which turned half up, and shining through a coloured shade, gave a sufficient, but not a brilliant light. Says Adams: “I stood at the door on the threshold, half in and half out, and just when the girl had got past the clock to go into the kitchen, a well-dressed man appeared. I did not suspect him, and she said nothing; and he came up to me quite pleasantly. I did not suspect anything wrong for the minute. I thought the man was going to speak to me, till he got past me, and then I suspected something wrong, and by that time the girl ran into the kitchen and put the gas up and said it was all right, meaning her pulleys. I said: ‘Where is your mistress?’ and she went into the dining-room. She said: ‘Oh! come here!’ I just went in and saw this horrible spectacle.”

The spectacle in question was the poor old lady lying upon the floor close by the chair in which the servant had last seen her. Her feet were towards the door, her head towards the fireplace. She lay upon a hearth-rug, but a skin rug had been thrown across her head. Her injuries were frightful, nearly every bone of her face and skull being smashed. In spite of her dreadful wounds she lingered for a few minutes, but died without showing any sign of consciousness.

The murderer when he had first appeared had emerged from one of the two bedrooms at the back of the hall, the larger, or spare bedroom, not the old lady’s room. On passing Adams upon the doormat, which he had done with the utmost coolness, he had at once rushed down the stair. It was a dark and drizzly evening, and it seems that he made his way along one or two quiet streets until he was lost in the more crowded thoroughfares. He had left no weapon nor possession of any sort in the old lady’s flat, save a box of matches with which he had lit the gas in the bedroom from which he had come. In this bedroom a number of articles of value, including a watch, lay upon the dressing-table, but none of them had been touched. A box containing papers had been forced open, and these papers were found scattered upon the floor. If he were really in search of the jewels, he was badly informed, for these were kept among the dresses in the old lady’s wardrobe. Later, a single crescent diamond brooch, an article worth perhaps forty or fifty pounds, was found to be missing. Nothing else was taken from the flat. It is remarkable that though the furniture round where the body lay was spattered with blood, and one would have imagined that the murderer’s hands must have been stained, no mark was seen upon the half-consumed match with which he had lit the gas, nor upon the match box, the box containing papers, nor any other thing which he may have touched in the bedroom.

We come now to the all-important question of the description of the man seen at such close quarters by Adams and Lambie. Adams was short-sighted and had not his spectacles with him. His evidence at the trial ran thus:

“He was a man a little taller and a little broader than I am, not a well-built man but well featured and clean-shaven, and I cannot exactly swear to his moustache, but if he had any it was very little. He was rather a commercial traveller type, or perhaps a clerk, and I did not know but what he might be one of her friends. He had on dark trousers and a light overcoat. I could not say if it were fawn or grey. I do not recollect what sort of hat he had. He seemed gentlemanly and well- dressed. He had nothing in his hand so far as I could tell. I did not notice anything about his way of walking.”

Helen Lambie, the other spectator, could give no information about the face (which rather bears out Adams’ view as to her position), and could only say that he wore a round cloth hat, a three-quarter length overcoat of a grey colour, and that he had some peculiarity in his walk. As the distance traversed by the murderer within sight of Lambie could be crossed in four steps, and as these steps were taken under circumstances of peculiar agitation, it is difficult to think that any importance could be attached to this last item in the description.

It is impossible to avoid some comment upon the actions of Helen Lambie during the incidents just narrated, which can only be explained by supposing that from the time she saw Adams waiting outside her door, her whole reasoning faculty had deserted her. First, she explained the great noise heard below: “The ceiling was like to crack,” said Adams, by the fall of a clothes-line and its pulleys of attachment, which could not possibly, one would imagine, have produced any such effect. She then declares that she remained upon the mat, while Adams is convinced that she went right down the hall. On the appearance of the stranger she did not gasp out: “ Who are you? “ or any other sign of amazement, but allowed Adams to suppose by her silence that the man might be someone who had a right to be there. Finally, instead of rushing at once to see if her mistress was safe, she went into the kitchen, still apparently under the obsession of the pulleys. She informed Adams that they were all right, as if it mattered to any human being; thence she went into the spare bedroom, where she must have seen that robbery had been committed, since an open box lay in the middle of the floor. She gave no alarm however, and it was only when Adams called out: “ Where is your mistress? “ that she finally went into the room of the murder. It must be admitted that this seems strange conduct, and only explicable, if it can be said to be explicable, by great want of intelligence and grasp of the situation.

On Tuesday, December 22nd, the morning after the murder, the Glasgow police circulated a description of the murderer, founded upon the joint impressions of Adams and of Lambie. It ran thus:

“A man between 25 and 30 years of age, five foot eight or nine inches in height, slim build, dark hair, clean-shaven, dressed in light grey overcoat and dark cloth cap.”

Four days later, however, upon Christmas Day, the police found themselves in a position to give a more detailed description: “ The man wanted is about 28 or 30 years of age, tall and thin, with his face shaved clear of all hair, while a distinctive feature is that his nose is slightly turned to one side. The witness thinks the twist is to the right side. He wore one of the popular tweed hats known as Donegal hats, and a fawn coloured overcoat which might have been a waterproof, also dark trousers and brown boots.”

The material from which these further points were gathered, came from a young girl of fifteen, in humble life, named Mary Barrow- man. According to this new evidence, the witness was passing the scene of the murder shortly after seven o’clock upon the fatal night. She saw a man run hurriedly down the steps, and he passed her under a lamp-post. The incandescent light shone clearly upon him. He ran on, knocking against the witness in his haste, and disappeared round a corner. On hearing later of the murder, she connected this incident with it. Her general recollections of the man were as given in the description, and the grey coat and cloth cap of the first two witnesses were given up in favour of the fawn coat and round Donegal hat of the young girl. Since she had seen no peculiarity in his walk, and they had seen none in his nose, there is really nothing the same in the two descriptions save the “ clean-shaven,” the “ slim build “ and the approximate age.

It was on the evening of Christmas Day that the police came at last upon a definite clue. It was brought to their notice that a German Jew of the assumed name of Oscar Slater had been endeavouring to dispose of the pawn ticket of a crescent diamond brooch of about the same value as the missing one. Also, that in a general way, he bore a resemblance to the published description. Still more hopeful did this clue appear when, upon raiding the lodgings in which this man and his mistress lived, it was found that they had left Glasgow that very night by the nine o’clock train, with tickets (over this point there was some clash of evidence) either for Liverpool or London. Three days later, the Glasgow police learned that the couple had actually sailed upon December 26th upon the Lusitania for New York under the name of Mr. and Mrs. Otto Sando. It must be ad mitted that in all these proceedings the Glasgow police showed considerable deliberation. The original information had been given at the Central Police Office shortly after six o’clock, and a detective was actually making enquiries at Slater’s flat at seven-thirty, yet no watch was kept upon his movements, and he was allowed to leave between eight and nine, untraced and unquestioned. Even stranger was the Liverpool departure. He was known to have got away in the southbound train upon the Friday evening. A great liner sails from Liverpool upon the Saturday. One would have imagined that early on the Saturday morning steps would have been taken to block his method of escape. However, as a fact, it was not done, and as it proved it is as well for the cause of justice, since it had the effect that two judicial processes were needed, an American and a Scottish, which enables an interesting comparison to be made between the evidence of the principal witnesses.