Early Dynastic Egypt (44 page)

The earliest depictions of a ritual hippopotamus hunt are to be found on a decorated pottery bowl dated to Naqada I from the cemetery at Mahasna (Ayrton and Loat 1911: pl. XXVII.13), an unprovenanced, incised, siltstone palette of similar date (Asselberghs 1961: pl. XLVI), and a fragment of the painted cloth from a Naqada II grave at Gebelein. All three examples show a hippopotamus being harpooned. Although there is considerable uncertainty about the details of the ritual, there is little doubt about its symbolic significance. The wild hippopotamus is a fierce creature, and must have posed a threat to fishermen and all those travelling the Nile by boat in early times. It was thus cast as an embodiment

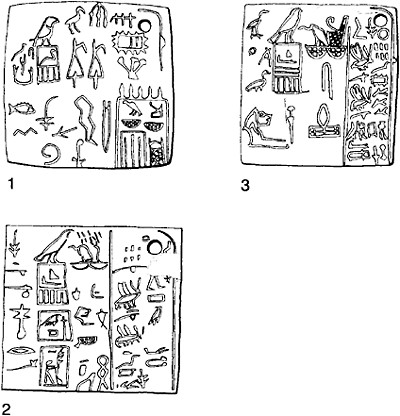

Figure 6.6

Hunting the hippopotamus. Evidence for an obscure royal ritual: (1) a fragment of painted linen from a late Predynastic tomb at Gebelein (now in the Egyptian Museum, Turin) showing a male figure harpooning a hippopotamus; this scene occurs in the context of other ritual

activities (after Galassi 1955:10, fig. 5);

(2) seal-impression of Den from Abydos showing (a statue of?) the king spearing a hippopotamus (after Kaplony 1963, III: fig. 364); (3) an entry from the third register of the Palermo Stone, referring to a year in the reign of Den as ‘the year of opening the lake “Thrones of the Gods” and hunting the hippopotamus’ (after Schäfer 1902: pl. I). Not to same scale.

of the forces of disorder, and in later times associated with the god Seth. The ritual spearing of a hippopotamus, a common theme in the decoration of Old Kingdom private tombs, represented an attack on chaos and struck a blow for the preservation of created order. The ritual doubtless emphasised the paramount role of the king to uphold Maat.

The presentation of tribute

Another commemorative macehead, from the reign of Narmer, has already been mentioned in connection with the ‘appearance of the king as

bỉty

’. The scenes on the macehead also depict another ceremony, namely the reception of tribute. Whether this occurred on a regular basis, or only after a military campaign, cannot be established. The Narmer macehead shows three bound captives being presented to the king. Three captives may represent a simple plurality, since the caption below states, ‘captives: 120,000’. The captives appear between the two sets of territorial markers previously encountered in depictions of the Sed-festival. These probably indicate that the ceremony took place in the court of royal appearance, perhaps within the royal palace compound. In addition to the captives, the booty presented to the king comprises 400,000 cattle and 1,422,000 sheep and goats. These figures are scarcely credible, and probably support a symbolic rather than a literal interpretation of the monument as a whole. Be that as it may, it is very likely that the booty of military campaigns was presented to the king in a formal ceremony, which may have resembled, in some respects, the scene on the Narmer macehead.

SPHERES OF ROYAL AUTHORITY

The royal monuments from the period of state formation—the late Predynastic and Early Dynastic palettes and maceheads—are, without doubt, ‘crucial sources for early kingship’ (Baines 1995:124). The scenes they carry express and define the role of the king

vis-à-vis

Egypt and the cosmos.

The primary duty of the king was to be the arbiter between the gods and the people of Egypt. Within this overarching role of kingship, there were none the less many other duties to be performed by the ruler. Moreover, the exigencies of government— maintaining political and economic control over the newly unified country—necessitated

a whole range of royal activities. These were intended to ensure the continued loyalty of the populace, the continued prestige and appeal of the institution of kingship, and the smooth running of the central administration. As might be expected, the best indications of such activities are to be found, not on monuments, but in documents more closely associated with the apparatus of government.

The evidence: year labels and royal annals

Important insights into early notions of kingship may be gained from a survey of the events considered worthy of record in the royal annals. The annals relating to the Early Dynastic period fall into two groups. First, there are the year labels (Figure 6.7). Second, there are the royal annals, comprising the Palermo Stone and its associated fragments.

The events shown on First Dynasty year labels can be divided into three broad categories, in order of frequency: religious ceremonies, royal visits and scenes of military activity. Uniquely, year labels of Qaa also record the foundation of a religious building and the collection of various timbers, doubtless as raw materials for the royal workshops (Dreyer 1993b: 10; Dreyer

et al.

1996:74–5, pl. 14.e). The last type of activity highlights the administrative purpose of year labels; and it is perhaps no surprise, therefore, that the events depicted convey a rather different impression of early kingship from that given by the surviving monuments from the period of state formation. The ceremonial palettes and maceheads are characterised by scenes of aggression and conquest, presenting a picture of the coercive, military aspect of royal power; this is also emphasised in some of the Horus names from the early First Dynasty. By contrast, the year labels concentrate on other royal activities, primarily the king’s participation in important religious ceremonies and royal visits to important national shrines. As was mentioned in Chapter 3, in connection with the royal annals, the system of naming a particular year after one or more significant royal events requires, on a purely practical level, that each year be so named at the beginning rather than the end of the twelve-month period: otherwise, it would have been impossible to label accurately commodities received and dispatched during the year. The implications of this fact are enormous: the events ‘recorded’ on the year labels must have been pre-planned or at least predictable. Scenes of apparent military conquest must, therefore, record an idealised view of events rather than actual campaigns.

A greater range of events is recorded on the Palermo Stone. Like the year labels, the annals include references to religious and royal festivals, royal visits and punitive actions against enemies, but other types of event are mentioned much more frequently. Although they cannot be used as objective sources for ancient Egyptian history (contra Weill 1961; Godron 1990), the annals do nevertheless constitute a rich source of information about

Figure 6.7

Year labels. Three First Dynasty labels, originally attached to commodities to record their contents and date: (1) wooden label of Djet from Saqqara (after Gardiner 1958:38); (2) ivory label of Qaa from Abydos (after Petrie 1901: pl. XII.6); (3) recently discovered label of Qaa from the king’s tomb at Abydos (after Dreyer

et al.

1996: pl. 14.e). Not to same scale.

early kingship, since every event recorded makes a deliberate statement about the king’s role and responsibilities.

The activities recorded

The events recorded on year labels and in the annals primarily reflect the concerns of early kingship and the self-image which the institution sought to project. Within this

overall framework, three interwoven strands are discernible, representing three aspects of the king’s role: his position at the head of the administration, and the overriding concern of the state for effective government, allowing total control of the country’s economic resources; his divine status as the representative of the gods, and his attendant duty to uphold their cults; his role, both ideological and practical, as defender of Egypt from the forces of chaos, real or supernatural.

The following of Horus

By far the most common event recorded for the reigns of Early Dynastic kings on the Palermo Stone is the

šms-Hr,

‘following of Horus’. From early in the First Dynasty, this activity seems to have taken place in alternate years. Although there appears to have been a temporary break in the tradition, perhaps during the middle of the First Dynasty, the

šms-Hr

was still recorded as a regular event early in the Third Dynasty. Despite a number of alternative interpretations (for example, Kees 1927; Kaiser 1960:132), the ‘following of Horus’ is most likely to have been a journey undertaken by the king or his officials at regular intervals for the purpose of tax collection: compare a decree of Pepi I, in which the phrase

šms-Hr

can scarcely mean anything other than an official tax-assessment and tax-collection exercise (Sethe 1903:214; von Beckerath 1980:52).

It has been suggested that the biennial royal progress allowed the king to exercise his judicial authority, perhaps deciding important legal cases, as well as permitting the detailed assessment and collection of tax revenues. It may be significant that the hieroglyph for

šms,

‘following’, used in this context, represents an instrument closely associated with the goddess Mafdet, and which can be interpreted as an executioner’s equipment (von Beckerath 1956:6). The king is likely to have been accompanied by all the senior members of the court during these royal progresses. Hence, the ‘following of Horus’ would have presented to the Egyptian people their government on a regular basis (von Beckerath 1956:7). The practice may be interpreted as a key element of the mechanisms of rule developed by Egypt’s early kings. It provided a regular forum in which the common people (

rh yt

) could pay homage, both personal and fiscal, to the ruler and his circle (

p t

). Moreover, the biennial royal tour of inspection allowed the government to retain tight central control over the country’s economic resources, ensured the regular payment of taxes to the royal treasury—to guarantee the continued functioning of the government apparatus—and reinforced the psychological ties of loyalty felt by the Egyptian populace towards the king.

Royal visits

Royal visits are commonly depicted on the surviving First Dynasty year labels. As befits a country where the primary artery of communication has always been the River Nile, these visits were made by boat. Three year labels record journeys undertaken by the king in the royal bark. Two of these, in the reigns of Aha and Djer, seem to have been to the Delta. The destination of the third, shown in abbreviated form on a year label of Semerkhet, is not identified. An entry for the reign of Den on the third register of the Palermo Stone records a royal visit to Herakleopolis to see the sacred lake of the local god Harsaphes

(hrỉ-š=f,

literally ‘he who is upon his lake’).

A wooden label of Aha from Abydos gives pride of place in the top register to a royal stop-over at the temple of Neith, a goddess with close connections to the First Dynasty royal family. In later times, the main cult centre of Neith was at Saïs in the north-western Delta. The second register of the label shows the shrine of

b wt

at Buto, supporting a Lower Egyptian setting for the events depicted. Of course, whether such a visit ever took place, or whether the label merely depicts an activity considered essential for the king to perform, is impossible to establish. However, the excavation of a substantial Early Dynastic building at Buto which yielded at least one official sealing dated to the reign of Aha makes an actual visit by the king a distinct possibility.

Other books

Winter's Kiss by Catherine Hapka

Lorelei by Celia Kyle

Born at Dawn by Nigeria Lockley

Return to Paradise by Pittacus Lore

Promiscuous by Missy Johnson

Valour and Vanity by Mary Robinette Kowal

A Tangle of Knots by Lisa Graff

Pearl of Great Price by Myra Johnson

Hide nor Hair (A Jersey Girl Cozy Mystery Book 2) by Jo-Ann Lamon Reccoppa