Early Dynastic Egypt (48 page)

Plate 7.1

The tomb of Qaa, during re-excavation by the German Archaeological Institute in 1992 (author’s photograph).This arrangement was maintained in the tomb of Qaa (Emery 1961:87; Plate 7.1). Initial excavation of Qaa’s tomb suggested ‘hasty and defective construction’ (Petrie 1900:14)—many of the bricks seem to have been used before they had dried completely, leading to the collapse of some walls—but recent re-excavation has shown that the

monument was built in several phases, apparently over a long period of time (Engel, in Dreyer

et al.

1996:57–71). The objects recovered from the tomb of Qaa by Petrie indicate that separate chambers were reserved for different categories of tomb equipment (Hoffman 1980:272). A new feature is the direction of the entrance stairway, which is now oriented to the north (Petrie 1900:4). This foreshadows the Second Dynasty royal tombs at Saqqara and the step pyramid complexes of the Third Dynasty which were aligned to the north.Funerary enclosures

From the reign of Djer onwards, it has been suggested that the ‘twin tomb’ of the late Predynastic and early First Dynasty kings was replaced by a single tomb on the Umm el- Qaab, accompanied by a separate funerary enclosure on the low desert nearer the cultivation (Kaiser 1964:96–102). The internal architecture of the late Predynastic tomb U-j supports the identification of the later enclosures as ‘funerary palaces’ (Kemp 1966:16). Their symbolic and architectural similarities with the Step Pyramid enclosure of Netjerikhet (Kaiser 1969) lend added weight to the hypothesis, although other interpretations have been suggested (Lauer 1968:82–3; Helck 1972). Whilst the long- term function of an enclosure may have been as a focus for the royal mortuary cult (O’Connor 1991:5, 7) and an arena for the eternal pageantry of kingship (Kaiser 1969:17), on a more practical level each enclosure may have served to protect the body of the deceased king until all the burial preparations had been completed. The permanent building identified in the south-east corner of Peribsen’s and Khasekhemwy’s enclosures may have housed the body of the dead king or sheltered his successor during the burial preparations. In addition, the enclosure may have been the location for some of the funeral ceremonies (Kaiser 1969:18–19).

To date, no enclosure attributable to Narmer or Aha has been located. None the less, the existence of further enclosures on the low desert is quite plausible, given the extensive area of largely unexcavated ground south of the Coptic village, Deir Sitt Damiana. First Dynasty funerary remains have been found over a wider area still, extending to the north-west of the village (Kemp 1966:15). Since the tomb of Narmer has no subsidiary burials, his funerary enclosure (if he had one) may, likewise, have stood alone. Without the lines of graves such as those that demarcate the enclosures of Djer and Djet, a possible early enclosure would be very difficult to identify archaeologically (Kaiser 1969:3, n. 3).

It was thought that the great size of the Djer and Djet enclosures precluded their having been permanent constructions of mudbrick (Kaiser 1969:3), but recent fieldwork has uncovered evidence of a mudbrick wall inside the Djer monument (O’Connor 1989, vindicating Kemp 1966:15). From the reign of Den, the enclosures were decorated with simple niches on three sides and more elaborate niches on the side facing the cultivation (Lauer 1969:83, 1988:5). The middle of the First Dynasty also witnessed a sharp reduction in the size of the monument (cf. Kemp 1966: pl. VIII; Kaiser 1969:3). Only at the end of the First Dynasty did funerary enclosures once again approach the size of the Djer and Djet monuments: the massive mudbrick walls of Deir Sitt Damiana may incorporate the funerary enclosure of Qaa (Ayrton

et al.

1904:2–3; Kaiser 1969:2). The late First Dynasty seems to have been characterised by a shift in emphasis—and,correspondingly, in expenditure—from the tomb on the Umm el-Qaab to the funerary enclosure nearer the town (Kaiser and Dreyer 1982:251). The change may reflect a conscious move towards more prominent royal funerary monuments as the visible expressions of divine kingship.

Like the enclosures of Djer and Djet, the structure attributed to Queen Merneith or her son Den (Kaiser 1969:1–2) is demarcated by lines of subsidiary burials. A deposit of First Dynasty pottery found inside the Merneith/Den enclosure (Kemp 1966:16–17) suggests that a building once existed here, as in the enclosures of the late Second Dynasty. The so- called ‘Western Mastaba’ lies immediately adjacent to the Merneith/Den enclosure, and shares the same dimensions and orientation. It is the earliest preserved enclosure to show the two types of niche decoration: simple niches on the north-west, south-west and south- east sides, and a more complex pattern of niches on the north-east wall (Kemp 1966:14). It provides a model for the reconstruction of the Merneith/Den enclosure although, unlike the latter, it is not provided with any subsidiary burials. This suggests that it dates to the latter part of the First Dynasty, when the practice of subsidiary burials was apparently dying out (Kemp 1966:15). It has been plausibly attributed to Semerkhet, penultimate king of the First Dynasty. If the Merneith/Den enclosure is attributed to Den and the ‘Western Mastaba’ to Semerkhet, then the only two rulers of the mid-and late First Dynasty without an identified funerary enclosure would be Merneith and Anedjib. The unique position of the former as queen regent but not monarch in her own right could explain her lack of a funerary enclosure; the absence of an enclosure for Anedjib could be explained by the apparent ‘emergency’ nature of his tomb (Kaiser and Dreyer 1982:254, n. 148).

A possible enclosure dated to the reign of Den has been identified at Saqqara, in addition to his putative funerary enclosure at Abydos. A group of graves excavated near the Serapeum (Macramallah 1940) has been interpreted as demarcating a ritual area (Kaiser 1985a). However, the burials are not all contemporary and the rows are not aligned at 90 degrees. The purpose of the feature is unknown, but one suggestion is that it was used for the embalming of the deceased king—assuming that he died at Memphis— before the body was taken south to Abydos for burial. Other similar enclosures of the First Dynasty have not yet come to light at Saqqara, although there are large unexcavated areas in the north-western part of the site, and it is quite possible that others may have existed along or on the edges of the Wadi Abusir. Alternatively, the Den installation could have been used by subsequent kings of the late First Dynasty, and this could account for the later dating of some of the graves (Kaiser 1985a). The proposal that the graves are subsidiary burials surrounding a large First Dynasty mastaba (Swelim 1991:392) seems unlikely since resistivity work in the area has uncovered no traces of any structure (Jeffreys and Tavares 1994:150 and n. 43).

Second dynasty

Saqqara

GALLERY TOMBS

The kings of the early Second Dynasty chose to abandon the ancestral royal cemetery of Abydos in favour of a new location overlooking the capital. This change in location must be significant, but the underlying reasons remain obscure (cf. Roth 1993:48). Not only did the tombs of the early Second Dynasty kings inaugurate a new royal cemetery, they also present an entirely new conception in royal mortuary architecture, both in terms of their size and layout (Kaiser 1992:182; cf. Munro 1993:49). Gone are the lines of subsidiary burials so characteristic of the First Dynasty royal tombs and funerary enclosures at Abydos. The practice of retainer sacrifice seems to have died with Qaa, a short-lived and no doubt wasteful experiment in absolute power. The two Second Dynasty royal tombs at Saqqara identified with certainty now lie beneath the causeway and pyramid of Unas (for example, Spencer 1993:105, fig. 80). Both tombs comprise a series of galleries, with blocks of store-rooms opening off a central, descending corridor hewn in the bedrock. Sealings found in the western gallery tomb bore the names of Hetepsekhemwy and Nebra. The eastern gallery tomb contained numerous sealings of Ninetjer, third king of the dynasty, identifying him as the probable owner.

The entrance section of the Hetepsekhemwy complex, open to the air after its initial construction, was subsequently covered by large limestone blocks (Munro 1993:49). The first series of magazines opens off the descending corridor, but access to the second series of magazines is blocked at the bottom of this corridor by a large granite portcullis slab. Three further slabs block the corridor at intervals (Stadelmann 1985:296). The published plan of the complex (Lauer 1936:4, fig. 2; Fischer 1961:46–8, fig. 9; Spencer 1993:104, fig. 79) ‘differs somewhat from the detailed verbal account given by the excavator’ (Roth 1993:43; cf. Barsanti 1902). In particular, the layout of the chambers is ‘by no means as regular and right-angled as depicted’ (Dodson 1996:22). In plan, the Hetepsekhemwy complex is very similar to contemporary private tombs (Roth 1993:44). The suite of rooms at the southern end of the galleries includes a large chamber to the west of the central axis, comparable to the burial chamber in Second Dynasty private tombs, and a more complex group of chambers to the east, reminiscent of the bedroom- lavatory-bathroom combination found in private tombs. The layout of the innermost chambers clearly imitates the private apartments of a house (Munro 1993:49; Roth 1993:44) and indicates that the tomb was conceived as a house for the

ka

of the deceased.

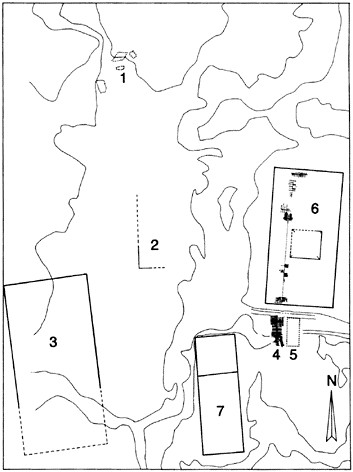

Figure 7.2

The royal cemetery at Saqqara. The plan shows the large number of Early Dynastic features in this part of the Memphite necropolis: (1) a group of graves dating to the reign of Den, possibly outlining a ritual arena; (2) and (3) two large rectangular enclosures of uncertain date (named the Ptah-hotep enclosure and the Gisr el-Mudir, respectively); (4) a set of underground galleries forming the tomb of Hetepsekhemwy and/or Nebra; (5) the location of a second set of underground galleries, forming the tomb of Ninetjer; (6)the Step Pyramid complex of Netjerikhet, incorporating several sets of underground galleries which may represent earlier royal tombs; (7) the unfinished step pyramid complex of Sekhemkhet (after Jeffreys and Tavares 1994:166, fig. 7; Lauer 1962: pls 6.a, 14.b).

The Ninetjer galleries follow a similar plan (Kaiser 1992:180, fig. 4d), although they cover a larger total area. Once again, the rooms do not follow a regular arrangement, perhaps due to the poor quality of the bedrock (Dodson 1996:22). There remains a small area adjacent to the Unas Causeway where traces of the original superstructure are visible (Munro 1993:49). The superstructure seems to have comprised two distinct elements. To the north, a platform floored with clay extended over an area some 20 metres deep, covering the outer passages and chambers of the tomb; it may have been used as a setting for funerary ceremonies. To the south, a rock-step may mark the location of a more massive, mastaba superstructure (Leclant and Clerc 1993:207; Dodson 1996:22). The rock-cut trench, noted by several writers as a prominent feature in this part of the Saqqara necropolis, may mark the edge of a platform upon which the Second Dynasty royal tombs were built. Two alternative reconstructions have been proposed for the superstructure of Hetepsekhemwy’s tomb: either a simple mastaba with sloping walls or a niched mastaba, like the First Dynasty mastabas at North Saqqara. The archaeologist excavating the Ninetjer complex considers it unlikely that the Second Dynasty gallery tombs were covered by large mastaba-like superstructures, because of the immense quantities of material which would have been required for such constructions (Munro 1993:50), and because little or no trace of massive superstructures has survived. However, it is possible that the superstructures were levelled by Netjerikhet during the construction or enlargement of his Step Pyramid complex, and the material reused (cf. Munro 1993:48, n. 49). The location of the Step Pyramid complex may indicate that the Second Dynasty superstructures were still standing when Netjerikhet’s monument was initially planned. In any case, the Second Dynasty tombs must have been in ruins by the Fifth Dynasty, allowing Unas to level the site for his pyramid complex.

Other books

End Zone by Don DeLillo

Wench With Wings by Cassidy, Rose D.

Perfectly Broken by Prescott Lane

Matters of the Heart by Danielle Steel

The Art of Self-Destruction by Douglas Shoback

And Then He Saved Me by Red Phoenix

White Lines by Banash, Jennifer

Will Starling by Ian Weir

With Her Completely by West, Megan

Ruthless: Mob Boss Book One by Michelle St. James