Early Dynastic Egypt (45 page)

A year label of the following reign seems also to record a royal visit to the same two Delta sites. The right-hand side of the top register shows a cult installation comprising buildings under palm trees either side of a wavy canal. Parallel depictions from later sources confirm Buto as the location for this installation (Bietak 1994). The second register presents a confusing array of signs, but at the right, an oval enclosure containing the red crown may signify a cult centre at Saïs, since the red crown was closely associated with the goddess Neith. The third register clearly shows the royal bark, next to a town identified by a bird. Exactly the same locality may well be depicted in the corresponding register of the Aha year label.

The fact that two consecutive kings of the early First Dynasty chose to record visits (real or symbolic) to the Delta is significant. The homage paid to Neith of Saïs and Wadjet of Buto by Aha and Djer probably indicates the significance of both sites before the unification of Egypt—in the case of Buto, this is confirmed by recent archaeological evidence—and emphasises one of the primary concerns of the early state: the determination to promote national unity through ideology and theology. The incorporation of Wadjet in the royal titulary—as tutelary goddess of the whole of Lower Egypt—and the pious references to Neith in the names of several Early Dynastic queens can be interpreted as two aspects of this programme. A visit by the king in person to the cult centres of the two goddesses would doubtless have served to strengthen the ideological bonds which held Egypt together.

Temple building and the dedication of divine images

A major duty of the king was to construct, beautify and maintain the temples of the gods. He performed this both as their representative and to ensure continued divine favour. In theory, therefore, the king was the ultimate high priest in every temple in the land. Implicitly, all temples were monuments to the king as well as cult centres for the deities to whom they were explicitly dedicated (Quirke 1992:81). Furthermore, the continual celebration of cult in temples throughout the land was vital for the preservation of cosmic order. Royal involvement in the life of temples could take one of two forms: the foundation and construction of a new temple, accompanied by a complex series of rituals; or a visit to an existing temple. We have seen royal visits to the temples at Saïs and Buto depicted on First Dynasty year labels, and a visit to the sacred lake of Herakleopolis recorded on the Palermo Stone. The royal annals contain several references to temple- building projects, as does a recently discovered year label of Qaa from Abydos. Temple foundation in the Early Dynastic period is dealt with in more detail in Chapter 8. An

important royal activity throughout Egyptian history, the Early Dynastic sources show that temple-building was considered a duty of kingship from the earliest times.

After the regular, biennial events—the ‘following of Horus’ and the census—one of the most frequent activities mentioned on the Palermo Stone is the fashioning or dedication

(ms)

of a divine image. A cult image was the dwelling-place for a deity, the physical embodiment of the divine presence. The creation of a new divine image necessitated the involvement of the king, since he was sole intermediary between the people and their deities, the high priest of every cult. The practice of dedicating divine images is considered in detail in Chapter 8. The year labels and annals give us some idea of the diversity of religious activities undertaken by the king. The emphasis placed upon the religious role of the king in the official record reflects its importance in Early Dynastic Egypt.

Military activity

Scenes of the king victorious over his enemies are not particularly common on year labels. Only two, one from the reign of Aha and one from the reign of Den, show events of a militaristic nature. The Aha year label, from Abydos, is incomplete, but seems to record (ritual?) military action against Nubia. The ivory label of Den from Abydos, already discussed, bears the legend

zp tpỉ sqr ỉ3bt,

‘first time of smiting the east(erners)’. If genuine, the label may record an early punitive raid against Egypt’s troublesome north- eastern neighbours (Godron 1990). Four fragmentary year labels of Den hint at military campaigns against Western Asia, as they seem to record the destruction of enemy strongholds (Petrie 1900: pl. XV.16–18, 1902: pl. XI.8).

Like the year labels, the annals of the Palermo Stone make only scant reference to military activity. A single entry on the third register refers to

sqr Iwntw,

‘smiting the Bedouin’. The nomadic inhabitants of the eastern or western desert were a persistent irritation to the Egyptian authorities, threatening the economy, stability and cohesion of the new state, and punitive raids were probably mounted at intervals to keep them in check. Whether the reference is to an actual event, or to the theoretical subjugation of Egypt’s enemies (a metaphor for containing the forces of chaos), cannot be determined.

More intriguing are the two instances which seem to refer to attacks on specific towns. The third register records an attack on a locality named

wr-k3,

determined by the usual town sign, indicating a settlement within Egypt. This is very significant, since it seems to suggest that a military campaign was mounted against an Egyptian town. It is not unlikely that occasional rebellions within the newly unified country would have taken place during the Early Dynastic period, and it is possible that the Palermo Stone records the royal response to just such an uprising. However, given the strong ideological content of the royal annals, a direct correlation between the written record and historical events cannot be assumed. In the fourth register of the Palermo Stone, similar attacks on two towns are mentioned. In this instance, the localities, whose names may be read as

šm-r

and

h3

(‘north’), are shown as rectangular, walled enclosures. It is possible that they represent places outside Egypt, although walled towns are also a feature of Early Dynastic settlement within Egypt. The reign in question is probably that of Ninetjer, and the attack on

šm-r

and

h3

has been associated with the apparent disturbances in the middle of the Second Dynasty.

Whether records of real events or expressions of ideal action, the references to military activity on the Palermo Stone emphasise the coercive power of early kingship. They also testify to the role of the ruler as suppresser of dissent and disorder, whether supernatural or human, from outside or inside his realm.

ARCHITECTURE AS A STATEMENT OF ROYAL POWER

The

serekh

and palace-façade

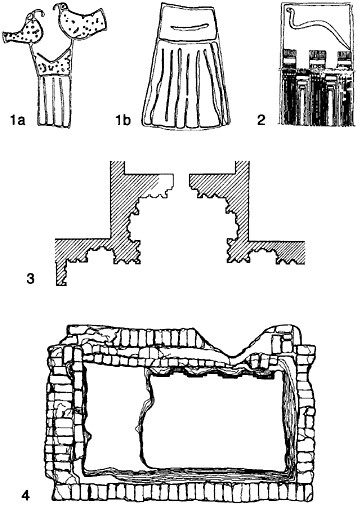

The

serekh,

enclosing the king’s primary name and proclaiming his identity as the incarnation of Horus, has been generally interpreted as depicting a section of the facade of the royal palace. The use of empty

serekhs

during the late Predynastic period shows that the motif alone was a powerful and readily understood symbol of royal authority and ownership. The role of the

serekh

in the early stages of Egyptian kingship not only emphasises the importance of iconography in establishing and propagating royal power, it also indicates the significant part played by architecture in this process (Figure 6.8).

In ancient as in modern times, the king’s palace was a powerful symbol of the institution of monarchy and of royal authority. (Compare the use of the term ‘pharaoh’— from

pr- 3,

‘great house’ [i.e. the royal palace] – to denote the king himself, from the New Kingdom onwards.) What seems to have made the royal palace a particularly suitable motif for use within the emergent iconography of rule was its distinctive appearance. The architectural style represented in two dimensions by the

serekh

panel is known to Egyptologists as ‘palace-façade’. The term denotes a mudbrick building with a series of recessed niches on the exterior walls, forming a decorative façade. Although the style is now best attested in Early Dynastic tombs and mortuary complexes, its connection with the royal palace, long assumed, has been confirmed by the excavation of a monumental First Dynasty gateway, presumably belonging to a royal palace, at Hierakonpolis in Upper Egypt (Weeks 1971–2).

The adoption of niched mudbrick architecture by the ancient Egyptians seems to have occurred in the late Predynastic period. Although the earliest surviving examples of the style date to the early First Dynasty (the Naqada royal tomb and mastaba S3357 at Saqqara, both from the reign of Aha), royal buildings of this appearance must have been in existence several generations earlier, probably as early as Naqada IId (

c.

3200 BC). Indeed, the two buildings from Aha’s reign show considerable sophistication in the decorative use of mudbrick, suggesting that the style was already long-established in Egypt (Frankfort 1941:334).

Origins

There is little doubt about the foreign origins of the palace-facade style (already noted by Balcz 1930; argued for strongly by Frankfort 1941; for a more cautious interpretation see W.S.Smith 1981:36; Kaiser 1985b: 32, proposes a Lower Egyptian origin). The similarity between Mesopotamian and Egyptian mudbrick architecture is so close as to make their independent development highly unlikely (Frankfort 1941:338; Kemp 1975a: 103). As with the adoption of Mesopotamian motifs into Egyptian royal iconography during

Naqada II, the process is likely to have involved an imaginative borrowing by the Egyptians from another culture to suit their own purposes: in both cases, the formulation of a repertoire of symbols to embody the ideology of divine kingship. The construction of a large-scale building of exotic appearance must have spoken to its viewers of power and prestige. It must have conveyed not only the economic potential of the ruler, but also a certain amount of awe. None the less, niched mudbrick architecture is unlikely to have been adopted merely for its dramatic impact. As with other borrowings from foreign cultures during the period of state formation and later, the Egyptian attitude seems to have been essentially pragmatic. If a neighbouring civilisation had already developed something for which the Egyptians perceived a need, the Egyptians showed no reticence in adopting it, then modifying and adapting it to suit their own purposes, ultimately creating a distinctive ‘Egyptian’ tradition.

An expression of élite status

The extent to which the palace-façade style of architecture became closely associated with the king—and thus a symbol of the élite status which derived from access to the royal court—is highlighted by the large First Dynasty mastaba tombs at Saqqara (cf. Kemp 1989:55). In common with contemporary élite burials at other sites, including Abu Rawash, Tarkhan and Naqada, these large mortuary constructions are decorated with recessed niches on their exterior walls. The architectural style proclaimed the status of the tomb owner, by emphasising his proximity to the ultimate source of power, the king. The élite symbolism of niched architecture was so strong that it was even used for the

internal

walls of a First Dynasty infant burial at Minshat Abu Omar (Kroeper 1992). Although invisible once the tomb had been finished and covered, the power of the architectural style to represent status was clearly undiminished.

The royal burial

The major construction project of each reign in the Early Dynastic period seems to have been the royal mortuary complex. It not only served as the burial place of the ruler, but also ‘advertised and embodied the objectives of the…state’ (Hoffman 1980:267). A monumental tomb symbolised both political power and communal leadership (Hoffman 1980:335).

The absolute authority of the ruler—his power over life and death – was given literal expression in a particularly chilling aspect of some First Dynasty royal burials at Abydos. The tombs on the Umm el-Qaab and the accompanying funerary enclosures nearer the cultivation were surrounded by smaller graves, belonging to members of the royal entourage. The household of King Aha—including his wives and other intimate attendants—was buried in a court cemetery, which stretched out from the royal tomb. From an analysis of the surviving skeletal remains, it appears that none of the individuals was older than 25 years, suggesting that the king’s retainers followed their royal master to the grave rather swiftly, whether voluntarily or by compulsion (Dreyer 1993b: 11). In subsequent reigns, the royal tomb was surrounded by a ring of subsidiary burials, the distribution of the graves echoing the situation in life. An altogether more absolutist form

Other books

The Stone Sisters: Lyssa (The Stones Sisters Book 1) by Clark, Bekah

StepBrother: New Rules (Stepbrother Romance) by King, Jayna

Victim of the Night (Night Trilogy Book 1) by E.R. Willis

The Tycoon's Socialite Bride (Entangled Indulgence) by Livesay, Tracey

Daisy Buchanan's Daughter Book 1: Cadwaller's Gun by Carson, Tom

[Redwall 18] - High Rhulain by Brian Jacques

War of the Werelords by Curtis Jobling

Conquering Alexandria by Steele, C.M.

My Lord Rogue by Katherine Bone

Dark Destiny (Dark Brothers Book #4) by Botefuhr, Bec