Authors: Joseph P. Lash

Eleanor (51 page)

At a Polo Grounds “Salute to Israel” meeting. To Mrs. Roosevelt’s left are Gen. Moshe Dayan and Abba Eban of Israel and George Meany, president of the AFL. Directly behind Mrs. Roosevelt is Ralph Bellamy, who portrayed FDR in

Sunrise at Campobello

.

Every summer the children of the Wiltwyck School for Boys picnicked at Val-Kill, and Mrs. Roosevelt would tell them stories—usually favorites from Kipling.

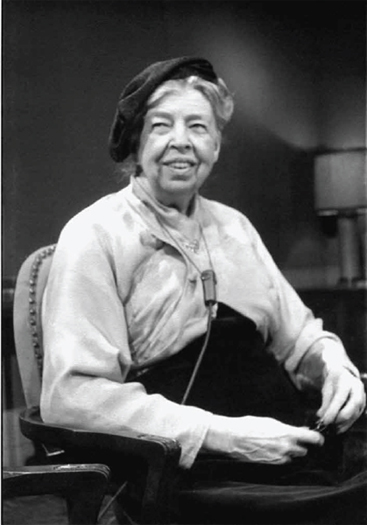

Roosevelt on her television program in 1961.

ELEANOR ROOSEVELT AND THE NOBEL PEACE PRIZE

S

EVERAL EFFORTS WERE MADE TO HAVE THE

N

OBEL

P

EACE

Prize awarded to Mrs. Roosevelt. In 1961 Adlai E. Stevenson, at that time United States representative at the United Nations, nominated her, not only because of the contribution that she had made to the drafting and approval of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but because “in this tragic generation [she] has become a world symbol of the unity of mankind and the hope of peace.”

1

A year later, when he renewed his request for consideration of Mrs. Roosevelt’s nomination, he was seconded by President Kennedy, who wrote the Nobel Committee that she was “a living symbol of world understanding and peace,” and that her “untiring efforts” on its behalf had become “a vital part of the historical fabric of this century.” An award to this remarkable lady, Kennedy added, “in itself would contribute to understanding and peace in this troubled world.”

2

This was nine months before Mrs. Roosevelt’s death. Death did not stop the efforts on her behalf. Ralph J. Bunche, himself a recipient of the prize, proposed that it be awarded to her posthumously. “I can think of no one in our times who has so broadly served the objectives of the Nobel Peace Award,” he wrote Gunnar Jahn, chairman of the Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Parliament, which made the award.

3

The prize went to Linus Pauling in 1962 and to the International Red Cross in 1963.

In the summer of 1964 a new effort got under way to obtain the prize for Mrs. Roosevelt posthumously. Lester B. Pearson, prime minister of Canada and a winner of the prize for his work in

establishing the first United Nations peace force, wrote Gunnar Jahn urging a posthumous award. “She certainly was an outstanding woman and I believe that the world does owe her a special debt of gratitude for her magnificent work for peace, and for the freedom and human rights on which peace must be based.” Nobel officials replied that the statutes of the Nobel Foundation prohibited the submission of the names of deceased persons. But Mrs. Roosevelt’s friends thought the committee, if it wished, could interpret the statutes to make the award. Andrew W. Cordier, Dag Hammarskjöld’s closest collaborator in the United Nations Secretariat, wrote Jahn pointing out that Mrs. Roosevelt had been nominated prior to her death, and in his view, therefore, she “technically qualifies under the rules of your Committee.”

4

At Adlai Stevenson’s request, the Norwegian ambassador to the United Nations, Sivert A. Nielsen, inquired whether Mrs. Roosevelt could not be awarded the prize since she had been nominated while alive. “My attention has been drawn to the fact,” Ambassador Nielsen added, “that the late Secretary-General [Dag Hammarskjöld] was awarded the prize post-mortem.” The director of the Nobel Committee did not find the parallel persuasive. “It is not possible to award the Nobel Peace Prize to Mrs. Roosevelt post-mortem,” he informed Nielsen. “The last time she was recommended was in 1962.” Nielsen took up the matter with Nils Langhelle, president of the Norwegian Storting and a member of the Nobel Committee. The rules of the Nobel Foundation concerning post-mortem awards, Langhelle replied, were interpreted to mean: “Deceased persons cannot be proposed whereas one who has been proposed and subsequently died can be awarded the prize post mortem for that year.”

5

Mrs. Roosevelt’s friends were not to be deterred. Since the 1964 prize had been awarded to the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., an organizing committee, consisting of the Dowager Marchioness of Reading, former publisher of the

New York Herald-Tribune

Mrs. Ogden Reid, and Esther Lape, undertook to secure consideration of Eleanor Roosevelt for the 1965 award. Twenty-eight distinguished citizens from all over the world sent supporting letters.

6

Former President Truman, with characteristic bluntness, wrote Gunnar Jahn:

I understand that there are regulations in your committee that rule out an award of the Peace Prize to Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt because she has passed away.

The award without the financial prize that goes with it can be made. You should make it. If she didn’t earn it, then no one else has.

It’s an award for peace in the world. I hope you’ll make it.

7

Clement Attlee, former British prime minister, wrote from the House of Lords with equal brevity and bluntness:

Eleanor Roosevelt did a great work in the world, not only for her fellow citizens of the United States, but for all people, and there is no doubt at all that if posthumous awards are given then the name of Eleanor Roosevelt should be among the recipients, and this nomination has my full support.

8

“If there is anyone who serves the posthumous award of the Nobel Prize it is she,” wrote Jean Monnet, father of the Common Market:

Fundamentally, I think her great contribution was her persistence in carrying into practice her deep belief in liberty and equality. She would not accept that anyone should suffer—because they were women, or children, or foreign, or poor, or stateless refugees. To her, the world was truly one world, and all its inhabitants members of one family.

9

Letters of support came from United States cabinet members and senators as well as from foreign statesmen.

*

Two former presidents

of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, Charles Malik of Lebanon and René Cassin of France, endorsed the nomination. One letter came from a Harvard professor of international relations in whose class Eleanor Roosevelt had regularly lectured and who later would become better known. “As someone who knows Mrs. Roosevelt for many years,” wrote Henry A. Kissinger,

and admired her work all his adult life, I can say that she was no ordinary person, not even an ordinary Nobel laureate. Mrs. Roosevelt was one of the great human beings of our time. She stood for peace and international understanding not only as intellectual propositions but as a way of life. She was a symbol of compassion in a world of increasing righteousness. She brought warmth rather than abstract principles. I am convinced that recognition of her quality would move people all over the world. . . .

10

“We have no illusions about the flexibility of the Nobel Committee,” Esther Lape wrote David Gurewitsch. “Its statements reflect a rigidity

extraordinaire

. But that the views of these distinguished persons in the United States, United Kingdom, Japan, and France will have an impact on the Committee, I cannot doubt.”

11

The 1965 prize was awarded to UNICEF.

*

The alphabetical list of those who wrote letters is as follows: Clement Attlee, David Ben-Gurion, René Cassin, Horace Bishop Donegan, Paul H. Douglas, Sir Alec Douglas-Home, Orville L. Freeman, Arthur J. Goldberg, Nahum Goldmann, Arthur L. Goodhart, W. Averell Harriman, Hubert H. Humphrey, Henry A. Kissinger, Eugene J. McCarthy, Charles W. Malik, Mike Mansfield, Jean Monnet, Reinhold Niebuhr, Philip J. Noel-Baker, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Walter P. Reuther, Nelson A. Rockefeller, A. L. Sachar, the Baron Salter, Margaret Chase Smith, Yasaka Takagi, who wrote jointly with Shigehabu Matsumoto, Harry S. Truman, Stewart L. Udall.

MRS. ROOSEVELT AND THE SULTAN OF MOROCCO

E

LEANOR

R

OOSEVELT’S SUPPORT OF

I

SRAEL WAS A CONTINUING

one. In 1956 Judge Justine Wise Polier came to her, distressed over the plight of more than ten thousand Moroccan Jews who had reached Casablanca in order to go to Israel and who were now being prevented from leaving. They were living in conditions of misery with the danger of an outbreak of epidemic ever-present. The World Jewish Congress, organizer of the exodus which it thought had the support of the sultan of Morocco, was distraught.

Mrs. Roosevelt listened and, “with the smile that lighted her face when she felt she could be of help to others,” told Justine that the latter had come at an opportune moment. She could help, she thought. She had recently received the ambassador from newly independent Morocco, who had come as an emissary from Mohammed V, the sultan, to Hyde Park to lay a wreath on FDR’s grave. The ambassador had arrived with such a large entourage from his embassy and from the State Department that Mrs. Roosevelt had not even had enough food for tea and had to send out for more. When tea was over the ambassador had asked for a few moments alone with her. The sultan had directed him to convey to her his deep appreciation of President Roosevelt’s advice to him in North Africa in 1943. The president had counseled him to protect Morocco’s underground waters when concessions would be given for exploration of oil after the war. The sultan would never forget Roosevelt’s consideration for the Moroccan people, and he wanted her to know that he was agreeing to the continuance of United States air bases in Morocco because of his gratitude.

This was an ideal time for her to write the sultan, Mrs. Roosevelt

said, her eyes twinkling. A few days later she dispatched the following letter:

July 31, 1956

Your Majesty:

I wish to acknowledge your kind message transmitted to me through your representative. It is very gratifying to know that you remember my husband’s visit to you. He often told me of that visit and of his hopes that some day you would bring back much of your desert into fertile land through the use of underground water which might be found, and he recalled his advice to you never to give away all of your oil rights since you would need a substantial amount of those rights to bring this water to the surface. To have you remember this and his interest in the welfare of these areas was very gratifying to me.

As you know, my husband had a great interest in bringing to people in general throughout the world better conditions for living. We tried to do this for the people of the United States, but he was also anxious to see it come about in the world as a whole.

I have had an appeal to bring to your attention the fact that there is a group of very poor Jewish people now in camps in Morocco who were to have been allowed to leave for Israel. They are of no value to the future development of Morocco as they have not succeeded in building for themselves a suitable economy. However, Israel can perhaps help them to develop skills and to improve their lot. Your government has given assurances that they would be allowed to leave but when it has come to a point in the last few months the actual necessary deeds to accomplish their departure have not been forthcoming.

I am sure that it is Your Majesty’s desire, as it was my husband’s, not only to see better conditions for your own people but to see people throughout the world improve their condition. I hope Morocco will show the world that she is committed, as I believe she is, to the freedom of people who are living

there which must include the freedom of people to emigrate. The Jews who had no country now have Israel where they can take their less fortunate brethren and help them to a better way of life. It seems to me that the Arab states would be forwarding their own interests if they were to make this transfer possible. It would relieve the Arab states of indigent people and would show the world that they did have an interest in helping unfortunate people to improve themselves. I, therefore, bring this situation to your attention in this note which primarily expresses my gratitude for your memory of my husband, since I believe that you would not have remembered my husband if you did not have somewhat similar aims.