Equilateral (14 page)

Authors: Ken Kalfus

“How do you mean?

“Side BC’s excavated and the last bit’s being paved today and tomorrow. Side AB’s coming along too.”

“They finished Side BC? It’s done?”

“But for the pitch.”

“That’s excellent news,” she says warily.

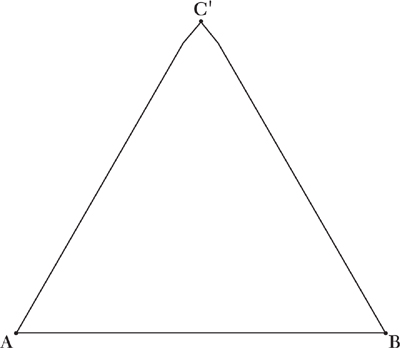

“We may be completed before maximum elongation; it now seems possible.” The engineer removes a sheet of foolscap from a stained, travel-beaten kit bag. “I need your opinion, Miss Keaton. What is this?” he says, holding up the paper to display a familiar geometric figure.

The bureau lamp flickers. Miss Keaton raises her guard. “It appears to be an equilateral triangle, but perhaps it’s not.”

Ballard insists, “It’s bloody close.”

“I don’t think so.”

“What’s wrong with it? How is it not an equilateral?”

Miss Keaton rests her eyes. She sees a true equilateral cast against the pale black screen on the inside of her eyelids. The triangle’s on fire.

When she opens her eyes, Ballard says, “I’ve already been in contact with London about this. The fellahin on Side BC were evidently overzealous in acquiring their extra wages. They went off the surveyed line. They veered northwest toward Side AC, with the connivance of their foremen. This happened about thirty miles from Point C. At the same time, I’m not sure how, they signaled their dodge to the corresponding workers on Side AC, who then turned sharply toward them. They eventually met at a point about eleven miles south of Point C. Call it C-prime, if you like. I’m told they’ve apparently established a tidy little settlement there.”

“Damn them! This is sabotage!” she cries. “This is mutiny! The entire undertaking depends on the Equilateral’s perfect form.”

Miss Keaton doesn’t know how much connivance there was between the chief engineer and the errant work crews. Perhaps this deceit was to be expected. Every engineer cuts corners. It may be intrinsic to the process of turning abstract ideas—infinite lines extending across boundless planes—into tangible, non-Platonic substance. Yet the Equilateral is like no other engineering project in the history of mankind: its tangible, physical reality

is

the Platonic.

She says, “It has to be rectified. They need to fill in the misplaced lines right away and excavate the new segments to Point C. There’s no time to lose. Hire more fellahin.”

“Miss Keaton, I’m afraid that’s impossible. We’re just a few weeks from maximum elongation.”

“It

can

be done! For years men have been telling us that the Equilateral is impossible, that the funds could not be raised, that the fellahin could not be assembled and quartered, and that the spades, the water, and the petroleum could not be acquired and transported to the desert. They’ve been proven wrong on every count. The Equilateral can be completed and the Flare can be ignited—properly and in time!”

Ballard shows her the foolscap again.

“Look at this,” he says. “It’s a scale representation of a triflingly irregular polygon. The deviation from C to C-prime is a little more than four percent of a line drawn from C to the midpoint of AB. If you resketch it as an isosceles triangle, the angles at the base are just one-point-two-nine degrees less than an equilateral’s. At their distance, the observers on Mars won’t distinguish the figure from an equilateral triangle any better than you can.”

“I can,” Miss Keaton insists. “Anyway, it’s dim in this room. I’m fatigued. You’re not holding the sheet steady.”

Ballard says, “Observers on Mars won’t enjoy entirely favorable conditions either. Even at maximum elongation, they’ll have to contend with the solar glare. They’ll have to peer down through our wet, heavy atmosphere. And their telescopes’ optical qualities will be limited, just as ours are.”

“How can we be certain of that? We know nothing of their instruments. They may have telescopes capable of resolving

Point A itself. It’s not impossible that they may observe the workers’ quarters, the excavation equipment, the water carts—even the ruts in the sand left by the water carts!”

“If they’re so far practiced in their telescopic skills, Miss Keaton, they won’t have needed us to provide them with an equilateral triangle. Whatever their level of superiority, they’ll forgive us our not-quite-equilateral. They’ll recognize that we employ lazy, careless workers. They’ll draw certain not-inaccurate conclusions about our civilization’s immaturity. But they’re scientists. They’ll find our faults interesting, perhaps as lessons that give them perspective on their own distant, troubled past. Our shortcomings will be the subject of a report to the Mars Astronomical Society. Be at ease. We may yet make some Martian astronomer’s career.”

“Professor Thayer will be furious.

I’m

furious. While he’s been ill, everything’s been overturned—with only weeks to go. The poor man … This will break his heart.”

“I think you’re right,” Ballard says evenly. “It’s a blow. In his fragile condition …”

“You must reexcavate the sides!”

Ballard again shows her the figure. This time it startles her, bringing color to her cheeks.

“Sir Harry has seen this,” he says. “He’ll keep it to himself. We needn’t tell the press. We needn’t tell Professor Thayer. For the purposes of the endeavor, he’s achieved what he set out to do. History will recognize him for that. We needn’t let a trivial discrepancy spoil his moment of triumph.”

“It’s not trivial,” she declares, but she concedes, through her rage, the insupportability of her position. A little more than 4

percent, 1.3 degrees. And if what’s at stake is Thayer’s well-being, even his life …

She shakes her head vehemently, looking away, down at her desk and the useless reports. She neither acknowledges Ballard’s departure nor his suggestion.

While the false Point C Vertex is excavated and lined with pitch—a blot in the desert, a stain on the endeavor, a rat that gnaws at Miss Keaton’s shivering heart—the project nears completion and the Red Planet rises in the Egyptian sky, on its way toward opposition, just as Earth ascends in the violet, hour-long evening dusk of Mars. Further accidents are reported and additional work stoppages have to be curbed, and rumors of more insidious unrest percolates among the overseers, yet the Equilateral moves, like the silently gliding planets themselves, toward its appointment with maximum elongation. The last section of the petroleum line arrayed around the triangle is laid. Each of its three hundred and nine taps have been installed.

As anticipation of the Equilateral’s completion seizes the fellahin, who continue to maintain an imperfect understanding of its purpose, Point A is jolted by news that the settlement will be inspected by the Khedive himself, said to be a monarch of cunning, culture, and enlightenment. He will be accompanied by no less a dignitary than Sir Harry.

The excitement’s enough to rouse Thayer from his sickbed.

Bint gives him a haircut. He steps from the tent wan and unsteady, but he’s fully heartened, not only by the coming visit, but also by the Red Planet’s increasing proximity. Every day it’s another half million miles closer to Earth.

Ballard is forced to take men off the Equilateral to prepare suitable accommodations and tidy up Point A, which after two years of hard service has fallen into a disorder barely remarked by its inhabitants. Latrines that have caved in have been incompletely filled. Chickens peck between tents, many of which are slack and roughly patched. A costly puddle of water leaks from the hammam. Broken machinery has been left where it failed. Unsightly structures have gone up adjacent to the Nag Hammadi track, in Point A’s outlying districts and suburbs. Ballard orders them rebuilt. The engineer is furious at the delays entailed by these preparations, especially as the improvements will be abandoned in weeks, immediately after maximum elongation, when the project is concluded.

Thayer is surprised that Sir Harry himself is coming to Point A. The astronomer shared rostrums and headlines with him as the Concession’s capital was raised, yet since ground was broken he has become a reclusive figure, in communication with Thayer only intermittently, and usually only on the subject of expenses. This is his first journey to the Western Desert. It’s unclear whether he still comprehends the project, and whether he still believes in it.

Δ

When the chairman of the Board of Governors is lifted from his carriage, the fellahin who are aware that he’s a Knight of the British Empire wonder from which untimely, ill-favored Crusade he’s returned. The pale and disheveled Englishman seems debilitated from the desert’s rigors. The men set him on his feet. He takes a few steps forward and vomits onto the sands.

The astronomer announces, “Sir Harry, we welcome you to Point A, the Vertex of Angle BAC, the southernmost and westernmost point on the Equilateral! We hope to make your stay here as comfortable as possible.”

Sir Harry replies, “It’s certainly cost me enough.”

The military orchestra assembles around the Khedive’s carriage. The entire camp turns toward the vehicle. The royal fanfare begins and is aborted several times before the Khedive finally appears, his uniform neatly pressed, his cap perfectly set. A large man, with a barrel chest that bulges against his tunic, he waves as if vast armed legions stand behind the orchestra. He bows to Miss Keaton and clasps the hands of the astronomer and the engineer.

Due to the governor’s indisposition, and also because of the intense heat, the welcoming pleasantries are curtailed to a brief rededication of the settlement, which is to be called Point Khedive Abbas Hilmi II in perpetuity. That evening a supper under the fixed stars and wandering planets is prepared by royal chefs with provisions brought from Cairo. Thayer delivers a stirring address that reminds his audience of the Equilateral’s high purposes. Ballard reads the text written for Sir Harry, who is

still ill and looks on balefully. The Khedive’s remarks are reiterated in six languages. The company retires early, in preparation for the following morning’s balloon ascent.

Δ

The machine has been shipped from London and inflated overnight in the scrub a few steps from the former site of the scaffold, whose remnants have been scrupulously removed. Beneath the swaying gas envelope an observation car is stamped with the words: MARS CONCESSION. The Khedive is delighted; he’s said to take a keen interest in modern technology, examples of which, including telephones and flush toilets, are installed throughout his palace, according to amused visitors from the English colony. He briskly questions the pilot, a dark, taciturn junior officer in the Royal Navy who has served aboard the Khedive’s Suez yacht, the

Mahroussa

. The Khedive poses a singularly original question. Did not Amenhotep III’s Eighteenth Dynasty employ similar vehicles for flight? He recalls an inscription to that effect on the Third Pylon, in the Temple of Amun. The sailor replies in vague affirmation, assuring him that he’s perfectly familiar with the balloon’s classic Egyptian provenance, as well as with its modern operation. Ballard notes the shifty response.

Sir Harry hardly seems to have benefited from having passed the night in the guest house that was constructed for his use and furnished with a featherbed and brass lavatory fittings. Through fatigue-rimmed eyes he looks at the ascension balloon with disgust, as if it’s yet another device designed primarily

for his discomfort. Ballard asks if he would prefer to remain in camp.

“No, I’ll do it,” he says through gritted teeth.

The balloon’s shadow dances among the dunes. Some inexplicably idle fellahin observe the party from a distance, their expressions passive, as if Montgolfiers are common desert flora.

The pilot welcomes the Khedive, Sir Harry, Ballard, Thayer, and Miss Keaton onto the gondola, which hovers inches off the ground, its ballast bags loaded with sand—imported from Britain with the gondola. The vehicle rocks as it takes on the passengers’ weight. Ballard briefly reflects, before an ascent hardly as dependable as a lift’s, that it carries the four men essential to the Equilateral and the millions of pounds sterling that have been invested in it. Gripping the gondola’s railing, the aeronauts wave to the onlookers, a small party of Europeans and the Khedive’s entire entourage, including the military band, which performs “God Save the Queen” and the Egyptian national anthem, composed by Verdi.

The land they’ve been excavating suddenly drops away, accompanied by applause and hurrahs. Point A is far below at once.

As the sun-bleached tents and mud-brick structures of the settlement recede, Thayer murmurs surprise. In his carriage with Bint a few weeks ago, he thought he was circumnavigating a burgeoning metropolis. But very quickly now Point A is seen to be a modest desert outpost, a few hundred yards square, a cluster of tents and buildings, of which only the hammam and the pitch factory may be recognized.

Then the two sides of the triangle radiating from Point A come into view, diverging toward points beyond the horizon three hundred miles apart, two black, throbbing lines laid into the sand, just as foreseen in Thayer’s letter to

Philosophical Transactions

in 1883, just as Ballard surveyed them in 1891 and ’92. They cut through whatever dunes or hillocks they encounter. Their blackness imprints itself on Thayer’s retinas. No one can doubt from this height or from any other that these are the artifacts of a sensitive, calculating intelligence. The balloon rises and the Equilateral continues to reveal itself.