Execution: A Guide to the Ultimate Penalty (29 page)

Richard Stopforthe, headed the 19th May 1574

James Smyth de Sowerby, headed at Halyfax the 12th Febr. 1574

Nicholas Hewett de North(awra)m, and Thomas Masone, vagans [vagrants], headed 27th May 1587.

Mention was made earlier that women guilty of theft were also beheaded on the gibbet, and over the years six suffered that fate. Women having little personal identity in those days, they are listed in the records as ‘Ux.’ (Latin

uxor

, meaning ‘wife’) together with their husbands’ names, as follows:

Ux. Thorn. Robarts de Halifax was headed the 13th July

Ux. Peter Harison, Bradford, decoll. [decollate, to behead] 22 Febr 1602 Ux. Johan Wilson decollata. July 5, 1627 Sara Lume, Halifax, decollata. Dec 8, 1627 Ux. Samuel Etall, on account of many thefts, beheaded Aug 28,1630.

And on 23 December 1623 it was recorded that ‘George Fairbanke, an abandoned scoundrel, commonly called Skoggin because of his wickedness, together with Anna, his spuria [pretended] daughter, both of them were deservedly beheaded on account of their manifest thefts’.

Midgley’s account of the last occasion on which the services of the gibbet were required throws a fascinating light on the way in which the ancient law was enforced:

‘

About the end of April,

ad

1650, Abraham Wilkinson, John Wilkinson and Anthony Mitchel were apprehended within the Manor of Wakefield and the liberties of Halifax, for divers felonious practices, and brought, or caused to be brought into the custody of the chief bailiff of Halifax, in order to have their trials for acquittal or condemnation, according to the custom of the Forest of Hardwick.’

The bailiff issued a summons to several constables of Halifax, Sowerby, Warley and Skircoat, charging them to appear at his house on 27 April 1650, each accompanied by four men, ‘the most ancient, intelligent and of the best ability’ within his constabulary, to determine the cases. The constables were merely the law officers, the jurors being the 16 ‘most ancient men’, the oldest and most experienced, in their police area. They were empanelled in a convenient room at the bailiffs house, where the accused and their prosecutors were brought face to face before them, as were the stolen goods, to be by them viewed, examined and valued.

The court was opened by an address by the bailiff, who said: ‘You are summoned hither and empanelled according to the ancient custom of the Forest of Hardwick, and by virtue you are required to make diligent search and inquiry into such complaints as are brought against the felons, concerning the goods that are set before you, and to make such just, equitable and faithful determination betwixt party and party, as you will answer between God and your own conscience.’

He then addressed them on the various charges against the prisoners. From Samuel Colbeck of Warley, they were alleged to have stolen 16 yards of russet-coloured kersey, which the jury valued at one shilling a yard. Two of the prisoners were alleged to have stolen from Durker Green two colts, which were produced in court, one of which was appraised at three pounds and the other at forty-eight shillings. Also, Abraham Wilkinson was charged by John Fielden with stealing 6 yards of cinnamon-coloured kersey and 8 yards of white kersey ‘frized for blankets’.

After some debate concerning evidence of the above, and further mature consideration, the jury adjourned until 30 April. On reconvening, they gave their verdict in writing, and directed that the prisoners Abraham Wilkinson and Anthony Mitchel ‘by ancient custom and liberty of Halifax, whereof the memory of man is not to the contrary, the said prisoners are to suffer death by having their heads severed and cut off from their bodies at the Halifax Gibbet, unto which verdict we subscribe our names’. The felons were accordingly executed the same day.

The stone base upon which the gibbet stood was discovered by the town trustees in 1840, when an attempt was made to reduce what was known as Gibbet Hill to the level of the surrounding ground. Except for some decay of the top and one of the steps, it was in perfect condition. It was then fenced in and an inscription affixed, which was done at the expense of Samuel Waterhouse, Mayor, in 1852.

It has been more recently restored, a replica frame and blade (securely immobilised!) being erected thereon. The actual blade, weighing 7 pounds 12 ounces, and measuring 10½ inches in length and 9 inches in width, was formerly in the possession of the lord of the manor of Wakefield; it is now exhibited, appropriately enough, in what once was the bartering centre of wool manufacturers, brokers and dealers, the magnificent Piece Hall in Halifax.

HANGED ALIVE IN CHAINS

‘[P]irates and robbers by sea are condemned in the Court of the Admeraltie and hanged on the shore at lowe water mark, where they are left till three tides have overwashed them...’

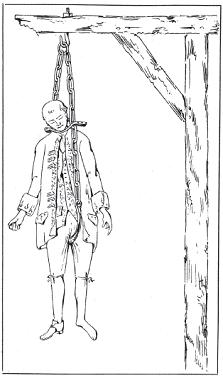

The actual details of this method of execution are unclear, but it would seem that more than one chain was used, several being wound around the victim’s body, another suspending him above the ground.

The chronicler Raphael Holinshed, who lived in the sixteenth century, referred to a law which stated:

‘But if he be convicted of willfull murther, done either upon pretended malice or in any notable robberie, he is either hanged alive in chains nere the place where the fact was committed (or else, upon compassion being taken, first strangled with a rope) and so continued! till his bones consume to nothing. And where wilfull manslaughter is perpetrated, the offender hath his right hand firstly stricken off.’

This was confirmed by dramatist and poet Henry Chettle (1540–1604) who, in praising Queen Elizabeth I, said:

‘But for herselfe she was alwayes so inclined to equitie that if she left [reduced] Justice in any part, it was to shew pitie; as in one generall punishment of murder. For where-as earlier there was the extraordinarie torture of hanging willfull murderers alive in chains, she, having compassion like a true Shepherdesse of their souls, even though they were often an erring and utterly infected flock, their death satisfied the one they had taken, for the extra torture [of chains] distracted a dying man.’

Earlier, in 1383, there occurred an unusual case involving hanging alive. The victim was an Irish friar who had appeared before Richard II and falsely accused the Duke of Lancaster of treason. His punishment was carried out thus, in the words of the historians:

‘Lord Holland and Sir Henrie Greene, Knight, came to this friar and putting a chain about his neck, tied the other end about his privie members, and after hanging him up from the ground, laid a stone upon his belly, so that with the weight whereof, and that of his bodie wit hall, he was strangled and tormented, so as his verie backe bone burst in sunder therewith, besides the straining of his privie members; thus with three kinds of tormentings he ended his wretched life. On the morrow after, they caused his dead corps to be drawne about the town, to the end it might appeare he had suffered worthilie for his great falsehood and treason.’

Being hanged in chains was also the penalty for piracy, this sentence being administered by the Court of Admiralty, a body set up to legislate on all maritime matters. The court had absolute powers over those who committed crimes while on board ship, even minor offences such as stealing ropes, nets or cords, anchors, buoys or similar equipment, and frequently prescribed the death sentence. In England this usually took place at Execution Dock on the Thames in London, because it was thought only fitting that those who committed such crimes should be put to death in or near water.

This practice continued from 1440, when two bargemen were hanged beyond St Katherine’s Dock for murdering three Flemings and a child in a Flemish vessel, ‘and there they hengen till the water had washed them by ebbying and flowyd, so the water bett upon them’; into the next century, when the chronicler Holinshed wrote, ‘pirates and robbers by sea are condemned in the Court of the Admeraltie and hanged on the shore at lowe water mark, where they are left till three tides have overwashed them’, and Machyn’s diary for 6 April 1557 reported ‘there was hangyd at the lowe water marke at Wapyng beyond Saintt Katheryns by the Tower, seven men for robyng on the see’; right up to 1735, when Williams the pirate was hanged at Execution Dock and suspended in chains at Bugsby’s Hole near Blackwall on the Thames. It is likely that the men were executed by being chained to a stake rather than hanged and so, in the spirit of the penalty, met their deaths, appropriately enough, by drowning.

Just as severed heads on London Bridge were considered an excellent deterrent, so too were the bodies of those hanged in chains on the banks of the Thames. Swaying with the tides, the waterlogged and bloated corpses provided dramatic warnings to the crews of the scores of ships which entered London, records showing that over 300 pirates were executed along the Thames each year.

A Thames pirate

The court’s jurisdiction, in view of this country’s trading prowess, extended worldwide, one fascinating case arising in the eighteenth century concerning, of all things, a woman pirate.

For some reason that can only be guessed at, Mary Read, at the age of three, was dressed as a boy by her mother, and not until she had attained the age of 13 was the truth revealed to her. Thoroughly attuned to her masculine role, however, she decided to continue as a male, and in 1706 joined the navy. Deserting from that service, she then enlisted in a foot regiment, switching to a cavalry regiment, where she fell so in love with the riding instructor that she admitted her true sex and married him.

Unfortunately, her husband died. Undaunted, she reverted to her previous disguise and, masquerading as a man, took ship for Jamaica. En route

the vessel was attacked and boarded by pirates, their captain recruiting ‘him’ as a ‘male’ member of his crew. Her career, worthy of a Hollywood film, continued, for she met another pirate, John Rackham, known as Calico Jack, with whom she roved the seas, Jack being kept oblivious as to her true identity, and by 1719 they had amassed so much booty that they had to bury it on a Caribbean island.

Jack temporarily gave up piracy on meeting a girl called Anne Bonny, whom he married; both he and his wife then returned to his previous career and joined up once more with Mary Read. In November 1720 their ship was captured off the coast of Jamaica and they faced trial in St Jago de la Vega before an Admiralty Court. Mary revealed her true identity, but, while awaiting trial, sadly died in prison. Anne Bonny was sentenced to death by the court, and Calico Jack and his crew were taken to Gallows Point, Port Royal, and there all were hanged in chains.